Editors at every level, from students to established professionals, question their creative abilities. From one day to the next, their feelings can go from total confidence to utter hopelessness. One reason for this emotional fluctuation is that editors lack a concrete method of measuring their progress. Their feelings are usually based on isolated events (e.g., screenings) that can go well or go poorly depending on a variety of factors — some of which they may not be able to control.

Mastery requires sustained effort, unflagging commitment, and resilience in the face of failure. Routine practice and critical thinking are the two vehicles of mastery, the results of which cannot — and should not — be measured from day to day.

On the journey to mastery, teachers are indispensable; they are great motivators and invaluable resources for knowledge that students may never discover on their own. However, teachers should be careful not to perfunctorily teach only introductory material. Furthermore, students have a responsibility to seek teachers who motivate them to improve. In the past, editors were expected to teach their assistants, but nowadays, assistant editors should not expect an editing apprenticeship to come with the job. Rather, assistants who aim to master editing need to consciously choose work based on whether they can be mentored on the job.

The rewards of mastery are just as unique and personal as the journey itself. Learning through critical thinking provides an enormous sense of pride — it enables people to understand their craft at a truly elemental level, leading them to produce their finest work.

For the last two years, I’ve been playing chess competitively. What began as a hobby has become a bona fide quest for mastery, which has given me insight into what it means to strive for mastery in my editing as well. While the skills for each discipline are very different, I believe that sharing my experiences in chess can allow me to tangibly illustrate what editors and editing teachers can do to make big strides on their paths to mastery.

The Journey

After a concert, an audience member told a classically trained pianist, “I would give anything to be able to play like you.” The pianist responded, “Give it four to eight hours a day, every day, for the rest of your life.”

Placing little importance on natural skill, author Malcolm Gladwell once said that mastering a skill takes 10,000 hours of practice. Practice is the process of gaining experience through critical thinking; critical thinking means applying a learned concept to a problem while trying to solve it. It’s crucial for editing novices to realize that their favorite editors are not naturally gifted — they are well rehearsed.

The first step of mastery is accepting that practice must become a part of daily life, since it’s consistent daily practice that keeps concepts fresh in one’s mind. This is the first time when a student’s passion is tested, because now they will have to make sacrifices — mainly, they must give up much of their free time — to improve.

Because so much time must be dedicated to achieve mastery, it is important that a newcomer enjoy the act of practicing in and of itself. When I first started playing chess, I would only think about the games I could play on the weekends. Now I don’t let a single day pass without at least solving some practice puzzles.

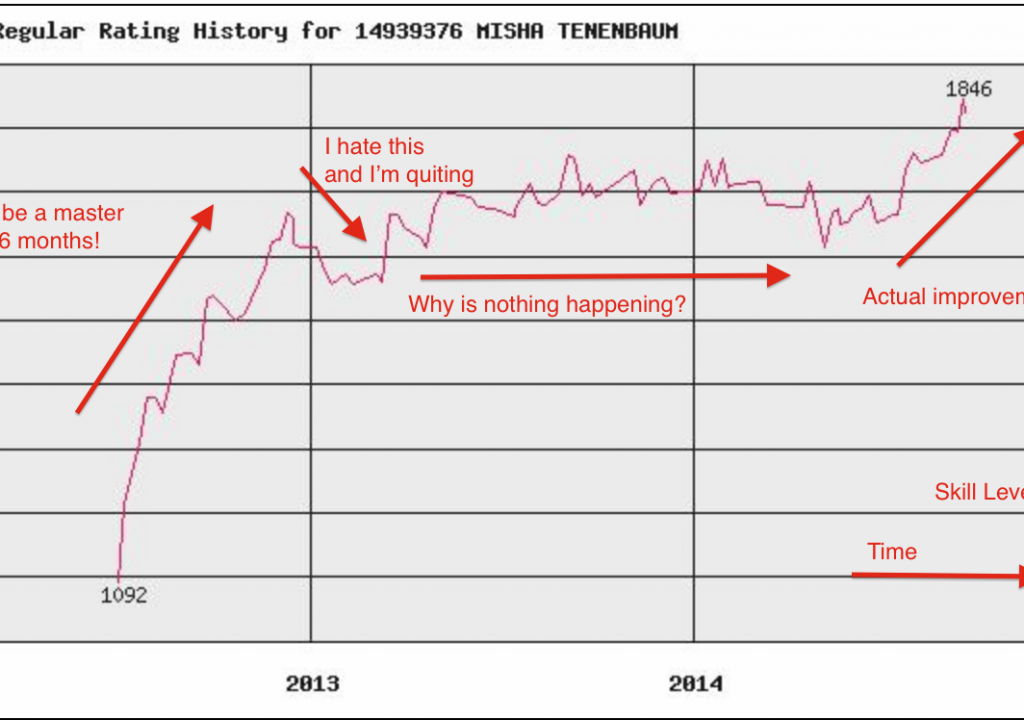

Measurable progress is a strong motivator. The United States Chess Federation (USCF) tracks a player’s skill through a rating system, using a scale of roughly 1 to 3000 (the higher the number, the better the player). A chess player with a skill level of 2200 earns the title of Master — literally. This concrete goal makes the quest clearer, but not necessarily easier.

The path to mastery is full of peaks, valleys, and plateaus in performance. I recently spent an entire year in the 1700-1799 range feeling like progress was impossible. It was discouraging to think that I had achieved my highest potential at a level not up to my standards. Students often feel similarly disheartened when they compare their work to others’, and conclude that they’re simply “not as gifted” as their classmates. If you feel this way, allow me to offer this advice: Practicing editing should be fun, even when it’s difficult. When you do make progress, there is no better feeling, because you will own it. It will be your improvement. Your work will become a source of pride because you’ll only have yourself to thank.

The path to mastery is full of peaks, valleys, and plateaus in performance. I recently spent an entire year in the 1700-1799 range feeling like progress was impossible. It was discouraging to think that I had achieved my highest potential at a level not up to my standards. Students often feel similarly disheartened when they compare their work to others’, and conclude that they’re simply “not as gifted” as their classmates. If you feel this way, allow me to offer this advice: Practicing editing should be fun, even when it’s difficult. When you do make progress, there is no better feeling, because you will own it. It will be your improvement. Your work will become a source of pride because you’ll only have yourself to thank.

The Role of Teachers

Six months after I started playing chess, I went from a beginner to an intermediate player. I was convinced that, within a year, I would be at least an expert player (2000).

Students and teachers love the early stages of learning. At this point, everyone is passionate about the material, and it’s often easiest for the students to absorb information after only hearing it and practicing it once. This is why teachers (myself included) love teaching introductory “101” courses. Everyone walks away happy: the students see significant and rapid improvement, while the teacher feel successful in imparting skills. However, after that 101 class, concepts become more complex, progress slows, and the need for practice and critical thinking only increases.

Improvement cannot take place without two basic levers; setting goals and accountability. Teachers are great aides in this cause because they provide accountability with their assignments/deadlines and goals with their grades. Furthermore, a teacher’s passion is contagious, motivating students to press onward even in times of failure.

Teachers effectively communicate strategies that students may not learn if left to their own devices. This is one reason why it’s so important to have teachers who are experts in their field. In one of my favorite editing classes as a student, a teacher shared the tip that, when picking reaction shots in a film, I should turn off the sound while watching the dailies. What a great idea! I may have never discovered it on my own.

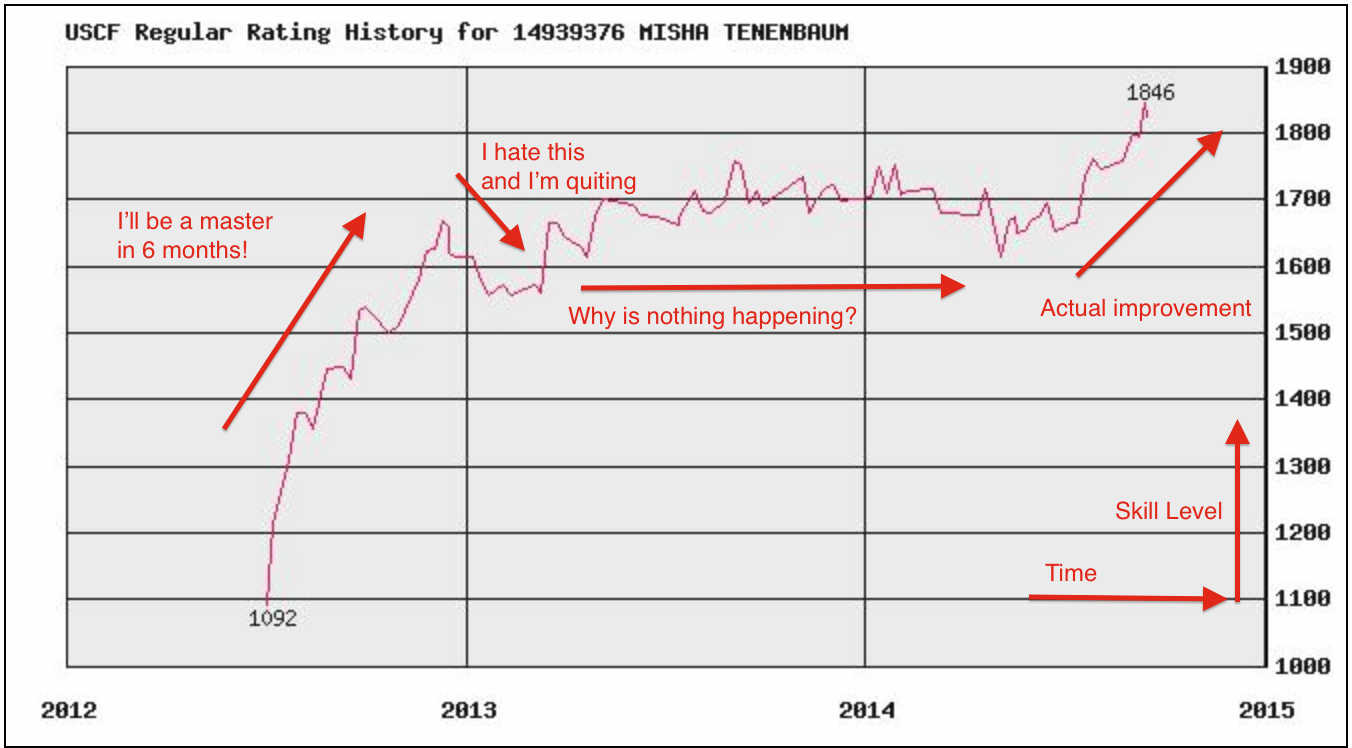

To the right is a graph showing the rate of improvement of two chess players. One has been working with a teacher, the other practices on his own. They both experience peaks and valleys, but the one with a teacher shows more overall improvement.

To the right is a graph showing the rate of improvement of two chess players. One has been working with a teacher, the other practices on his own. They both experience peaks and valleys, but the one with a teacher shows more overall improvement.

Those still learning to edit need to put themselves in a position where they have access to great teachers. In the past, this meant internships and apprenticeships. Today, it means film school and video tutorials.

While honing their technical skills is extremely important, assistant editors must also keep nurturing their creative sensibilities. When the opportunity arises to edit, assistant editors will be expected to perform like editors from day one. If you’re not editing, you are not getting better at it.

Why Try?

Mastering a craft means gaining a deeper understanding of the craft itself. When a person spends a lot of time working on their technique, subtle things gain a larger and clearer meaning. Masters quickly zero in on problems or advantages and exploit them. Masters experimenting in their work are often successful precisely because they see those problems and advantages. In other words, master editors are seeing the elements of a cut quicker than beginners are, and they are adjusting the cut to fix problems which they can easily identify. This level of focus is more productive than an amateur’s because masters don’t need to spend time searching for what to change — they see it right away.

In its most basic sense, the goal of practicing is the discovery of a craft’s basic elements as they apply to any given situation. Knowledge from past experience, combined with critical thinking, creates masterpieces.

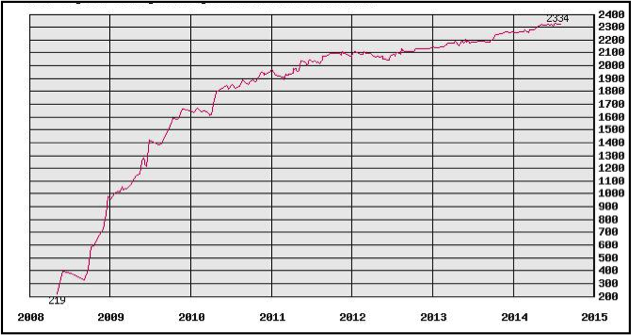

This is the chart of a 13-year-old who is a master chess player. People who hear about kids like this typically figure that they must be “naturals.” However, those who know this 13-year-old well would realize that he has been playing chess since he was seven. He started at the same skill level as everyone else, and he has experienced the same peaks and valleys. However, without taking three private lessons every week and studying on his own for several hours every day, his “natural gifts” would never have earned him the title of Master.

This is the chart of a 13-year-old who is a master chess player. People who hear about kids like this typically figure that they must be “naturals.” However, those who know this 13-year-old well would realize that he has been playing chess since he was seven. He started at the same skill level as everyone else, and he has experienced the same peaks and valleys. However, without taking three private lessons every week and studying on his own for several hours every day, his “natural gifts” would never have earned him the title of Master.

Steps Worth Taking

Now that we know what it takes to master a craft, below are some tips for editing teachers and their students. You can also check out what I recently had to say about Teaching Creative Editing.

Teachers:

- Pick projects your students can complete. We recommend that students practice editing projects that gradually increase in difficulty (e.g., start with a 90-second commercial, advance to a six-minute short film, and finally graduate to a 20-minute piece). For an experienced editor, every two minutes of finished footage should take approximately eight hours to cut. Students start out cutting slower than that — even a 90-second piece can feel overwhelming to them. Gradually increasing project lengths can help provide a sense of completion that reduces anxiety and keeps them from feeling overwhelmed.

- Don’t let one student edit everyone’s projects. Teachers should think of video editing as a form of video literacy. We wouldn’t let one student write everyone’s papers for them, so we shouldn’t let one student edit everyone’s projects (unless the class is collaborating on one project).

- Play the roles of director and producer. Watch your students’ work several times weekly (at least), since consistent feedback will accelerate their learning curve. Regularly checking on your students fosters a sense of accountability, encourages daily practice, and discourages procrastination.

Students:

- Edit. Professional editors cut 60-300 minutes of footage five days a week. If you want to edit professionally, practicing for at least 30 minutes each day should become a priority.

- Get feedback on your work. Professional editors receive notes on their work almost every day, so learning to understand and implement feedback is essential. EditStock is offering free feedback on any video with a runtime of 10 minutes or less (for more information, click here).

- Don’t be passive. While watching tutorials, remain actively engaged by following along in your editing software.

More from Misha Tenenbaum:

I Will Provide Professional Editing Services For $5

PVC meet EditStock, EditStock meet PVC

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now