The modern fashion for something we’ll term grunge in film and television pictures is something that future generations might see as slightly quaint. It’s certainly a little paradoxical that the desire for sparkling-clean, artifact-free pictures seems to have been almost inversely proportional to the capability of film and TV technology to provide them. More than that, though, there’s a popular view that historic cinema was perhaps more beset with grunge than it actually was. Are we really recreating the past, or just making up something new that feels like the past?

A good example comes from any attempt to actually recreate historic cinema. One of the most amusing jobs anyone in film and TV can be asked to do is to create the filmed inserts for a live performance of Singin’ in the Rain. Set in (presumably) late-1920s Los Angeles, any production of the stage musical requires several short scenes to be shot and projected in front of the audience, representing cinema as it existed at the dawn of sound. It’s a rich vein of nostalgia-by-proxy for the movies made in a time that’s almost completely faded from living memory, and anyone with even passing enthusiasm for the modern interest in grungy pictures might find a reason to be excited.

After all, everyone knows what old movies look like, right? Right? Monochrome, flickering, grain, scratches and instability. Lots of contrast, and of course, the sort of overacting that’s probably quite appropriate when the actors know that the dialogue is going to be cut in as white text on a black card. It’s good fun.

One of the productions that are shown in the film-within-a-show is ostensibly a talkie feature called The Dueling Cavalier, possibly a play on the real-world Rudolph Valentino vehicle Monseuir Beaucaire of 1924, set in France during the reign of Louis XV. Certainly, in the 1952 film Singin’ in the Rain, the production design of The Dueling Cavalier is depicted as being very close to that of Monsieur Beaucaire. Perhaps it’s just a UK thing, but lots of productions of the stage musical, looking to shoot their filmed inserts, have gone to great lengths to access real sixteenth-century locations.

Just like the real sixteenth-century European buildings that existed in Los Angeles in the late twenties, and which such an early talkie would, of course, have used.

Er, no. It wouldn’t have been a real location, especially not while we’re contending with the issues of very early sound recording. It would have been a bad set on a Burbank sound st… well, in a Burbank warehouse, possibly with straw on the floor and carbon arcs fizzling away overhead, a thoroughly fire-retardant combination if there ever was one. Anyway, when people shoot their Singin’ in the Rain inserts on actual sixteenth-century locations, they’re missing the point by a mile.

And in the same sense, those late-twenties pictures would not have looked as, well, grungy as modern sensibilities might assume. They’d certainly have been monochrome. Someone with a real eye for detail might even derive the pictures solely from the blue and green channels of a modern colour camera, the better to approximate what might still have been orthochromatic stock until about 1930. But flickering, unstable and scratched? That certainly wouldn’t have been what the manufacturers were going for.

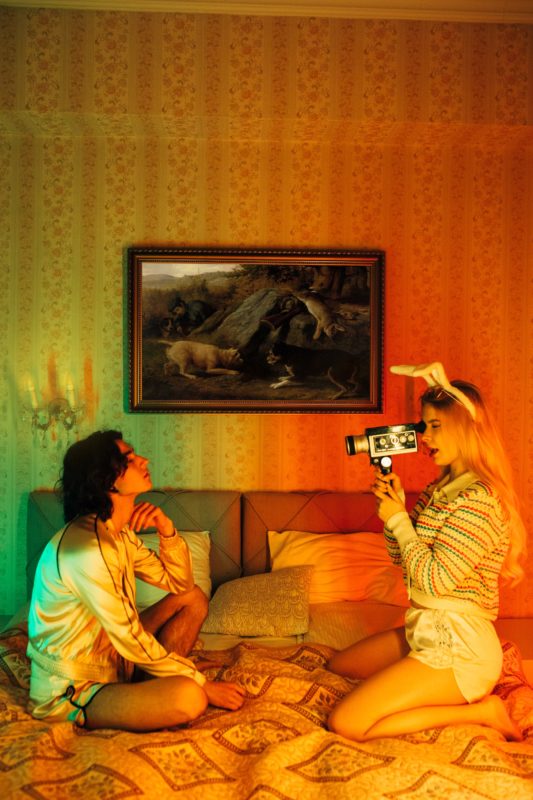

Similar things apply to the now-popular 1970s super-8 looks that have been deployed on commercials and music videos. There’s perhaps a little more legitimacy to this, not least because some of them have actually been shot on super-8, which has enjoyed a renaissance in the last few years. Even actual 1960s and 1970s super-8 was often shot in less-than-ideal circumstances on less-than-ideal equipment. Kodachrome was, to be nice, a highly responsive film stock that would happily create colour casts and grain if it was poked with an appropriate stick.

Recent efforts with high-quality scanning, though, have shown that well-shot, well-processed, well-stored holiday movies of decades past can actually look very respectable. When we grade shadows cool and highlights warm, crush the blacks and add grain to “make it look 70s,” we aren’t necessarily simulating what pictures of the period did look like; we’re imposing on the material our own expectations about what it should look like. While it wasn’t shot on Kodachrome, Star Wars is also a 1970s movie, and while its original elements have apparently suffered some quite serious colour fading, great restoration efforts have been made to keep it looking as if it were shot yesterday.

Probably the most recent incarnation of this sort of thinking is the fascination with VHS tape artifacts as if they simulate what VHS looked like to most people most of the time. What they’re mainly simulating is a VHS deck that’s malfunctioning terribly – but hey, if that’s what the people want.

This is not about history or technology, it’s about art. Hyper-reality is fine – but let’s be aware, at least, of what we’re doing.