Editor’s Note: “28 Weeks of Post Audio” originally ran over the course of 28 weeks starting in November of 2016. Given the renewed focus on the importance of audio for productions of all types, PVC has decided to republish it as a daily series this month along with a new entry from Woody at the end. You can check out the entire series here, and also use the #MixingMondays hashtag to send us feedback about some brand new audio content.

Meters, loudness, levels and the CALM Act can be a technical and somewhat confusing topic. I will try to make this useful with a minimum amount of geekery. As a point of reference for this article, we’ll use the current US standards for loudness.

First, a brief refresher on audio levels in general. Digital audio levels are expressed in decibels and are abbreviated by db or also sometimes dbFS or dbTP. Zero is maximum digital level, therefore; digital audio levels are expressed with a minus sign. In sound for picture mixing, calibration tones are set to -20db which allows for a “headroom” of 20 decibels until you hit full scale (dbFS).

As with digital video files, digital audio files have a variety of encoding schemes and resolutions. Standard digital audio for video files have a resolution depth of 24 bits and is sampled 48,000 times per second. Compared to the frame rates of video of 24 or 30 per second, digital audio can be extremely precise.

The main digital audio files in use today are broadcast wave files (BWav or Wav) and AIFF files. These are full fidelity, pulse code modulation (PCM) audio files. These files can come in mono, stereo and multi-track. From there, many additional encoded audio formats exist, typically compressed or “lossy”, like MP3, Dolby Digital or Pro Logic iterations. There are also higher resolutions of digital audio available as well. Sample rates can increase to as high as 192Khz and resolutions can become floating point at much deeper bit depths.

Various measurements and meters are required for proper audio mixing, output and delivery. Tracks, mixing, routing and signal flow will be an article for another week, but at its most basic, a meter will tell you what the audio levels are going in and what the audio levels are going out, at any given time. In sound for picture editing and mixing, there are quite a few meters that should be watched for proper audio delivery. Each individual track will have a meter showing the audio passing through it, be it dialog, sound effects or music.

Sound for film requires the artful blend of dialog tracks, music tracks and sound effects tracks mixed to the demands of the required deliverables. When creating the signal path for all of the elements, each stage of the mix must be monitored, since ultimately all of these signals will combine to create new levels and peaks. Besides the dialog, music and effects tracks for the design of a soundtrack there are many other tracks like auxiliary tracks, record tracks and various sub-mix tracks. Each of these tracks will also have to be metered, as will all of the busses sending and returning audio signals. There are a lot of levels to keep an eye on.

At the delivery stage of the soundtrack there will be a number of technical requirements that must be met – including proper sync to picture, proper audio phasing, the various sub-mixes and splits required and levels and loudness required. These specifications can include true peak level measures, LKFS loudness readings and average mix levels.

Regarding true peak meters, be aware that these are not the default meters in most non linear editors. These meters are sample peak meters and will indicate peaking at the sample level. True peak meters read between the samples for a more accurate measure. It’s important to note because if you are pushing “through the red” on your NLE mixer, your signals are actually even hotter than indicated. Great info in this paper from the BBC.

Side note for those of you tackling deliveries for the first time. Read everything carefully and then read it again and again. Don’t think that there is any section that will not apply to the audio deliverables. I’ve had delivery docs that have a section for “Audio Deliverables” and later in the tape laybacks or digital file deliveries there are stacks of other audio splits or sub-mixes that are indicated nowhere else in the document, sometimes with different loudness specifications. Read, read and read again. There are odd requirements like a 16 bit delivery and I’ve even had docs that ask for a 20 bit delivery. In those cases you need to find the person who runs the QC (quality control) for the network or distributor, and get the right answers.

Here is a sample of audio loudness requirements for a popular US cable station.

Stereo mix:

Average levels -25 to -18 dbFS, peak levels -14 to -10 dbFS, LKFS levels -24 +/- (2) dbFS

Surround mix:

Average levels -25 to -18 dbFS, peak levels -14 to -3 dbFS, LKFS levels -24 +/- (2) dbFS

Elemental Tracks:

Average levels -25 to -18 dbFS, peak levels –14 to -3 dbFS, LKFS levels Unrestricted

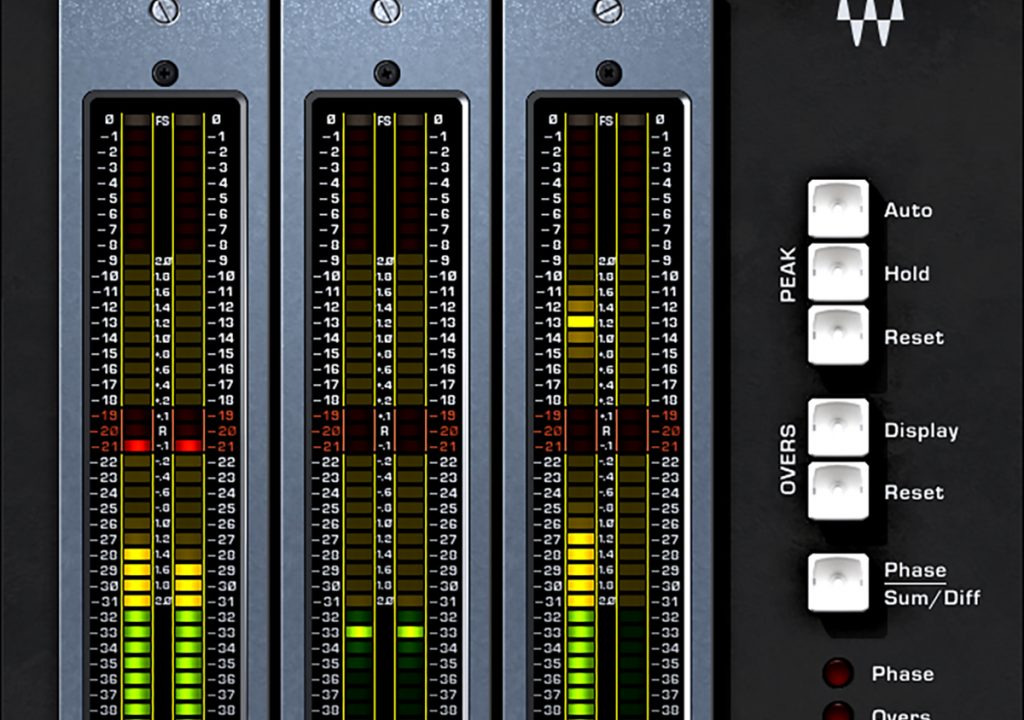

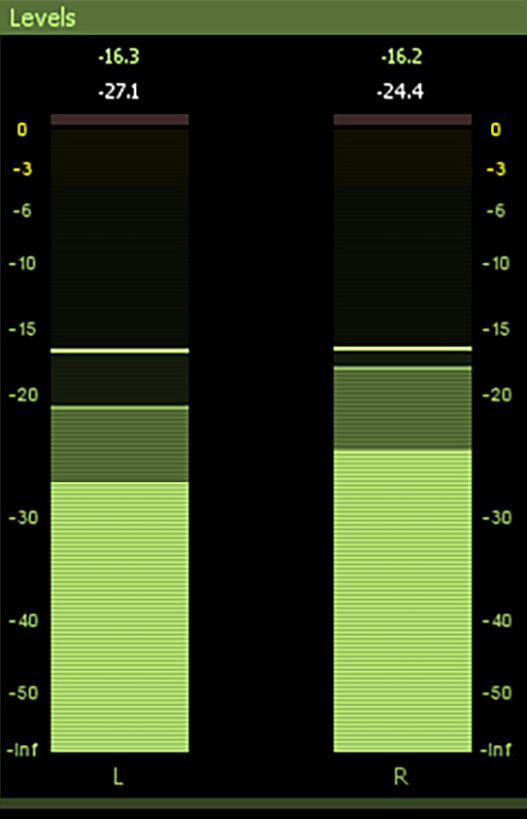

This is one set-up for monitoring a television series that I mix. Whenever I am mixing a program I always have the relevant meters up at all times. All program output levels must be monitored, in real time, through the appropriate meters to ensure compliance. Here I’m using three Dolby Media meters, one for the stereo full mix, one for the mono full mix, and one for the dialog only mix. I use iZotope’s Insight plug-in on the final full mix bus on signals sent to the record tracks. Here Insight is only showing a few levels and the sound field, but it’s capabilites are far deeper than shown here.

There were a lot of complaints from the US public to the Congress about the wildly varying volume levels between programs and between stations on television. The United States Congress passed a law that went into effect on December 13th, 2012. The law is called the Commercial Advertisement Loudness Mitigation Act or the CALM Act. This is a politics free zone so I’ll leave out all variations of comments that could be made about audio specifications and an Act of Congress… However, it has been adopted, implemented and self-enforced in television delivery. If there is no additional post audio for a given project, then the video editors must comply with these rules.

The CALM Act standards are based on the ‘‘Recommended Practice: Techniques for Establishing and Maintaining Audio Loudness for Digital Television’’ (A/85 by the Advanced Television Systems Committee – ATSC). It’s a technical document with many useful appendixes. The ATSC is a standards group made up of engineers and manufacturers.

CALM Act compliance standards in a nutshell are – -24LKFS +/- 2 dbFS, with a true peak reading of -2dbTP. If we don’t mix our television to these standards we are breaking the law! Well, in reality, we’d be breaking our delivery requirements and won’t pass quality control (QC) and won’t get paid… and that is certainly a crime!

Using CALM as a reference point, the meters required for those measures are specifically – an LKFS meter as well as a true peak meter. As mentioned, these are not typically the default meters in any given program. Insight and the Dolby Media Meter, two of my personal go-to measuring programs are additional purchase plug-ins to Avid’s Pro Tools, my DAW environment.

There are solutions today, be it native to the program, or as an add-on plug-in, that also can address loudness standards and peak level compliance. These are probably really handy for picture editors who can adjust levels well enough but don’t have the time or experience to create a fully compliant, LKFS mix output. I discuss one such tool, RX Loudness Control, in a prior post.

I am already mixing the program as I measure so, of course, I adjust my mix to keep levels in the sweet spot. For those who come from an analog audio world as I do, we’ve learned that “hitting the red” is no longer an option. VU meters were less sensitive and analog audio and gear was much more forgiving. Today it is imperative that you understand not only the levels that are required for your particular program but also understanding the tools that you are using to get there.

I have a more in-depth look at the CALM Act in a prior article on PVC here.

This series, 28 Weeks of Audio, is dedicated to discussing various aspects of post production audio using the hashtag #MixingMondays. You can check out the entire series here.

Woody Woodhall is a supervising sound editor and rerecording mixer and a Founder of Los Angeles Post Production Group. You can follow him on twitter at @Woody_Woodhall