The difference between a movie and a video is that a movie is created in the filmmakers’ minds and a video is created on a monitor.

Early video taps (which re-photographed the viewfinders’s ground glass) let everybody see the same useless image. Viewfinders and video taps improved, of course, but even with a good video image of a good viewfinder, you still couldn’t see the movie; film emulsions “see” differently than a person does, interpreting the image and thus the story.

Because they couldn’t actually see what they were filming, early filmmakers had to create the movie in their minds, using, among other talents, their skill with lenses and film stocks. The part of the mind used for this sort of thing is the imaginative part, the part that you dream with or remember your grandmother. Cinema was invented during this time.

Video comes from TV, where what you see is more or less what you get. Video makers created the video on monitors: this goes there; this moves from this part of the picture to that part of the picture. The part of the mind used for this sort of thing is the pattern recognition part, the part you use to find a lost contact lens. Video was invented during this time.

Film and video were different for the audience, too. In a movie theater, a film projector shows 48 images a second (each film frame is shown twice) alternating with 48 black frames a second. This means that half the time, when you are watching a film print (if you can still find one), you are looking at a black screen. You must fill in the black frames of the story with your mind: how his hand got from there to there, what he was thinking during that flicker in his eyes, where the bullet went. The audience uses the same imaginative part of their minds to watch the movie that the filmmakers used to create it.

On video monitors, there are no black frames: each image is followed by the next, answering all questions, describing the image for you. No audience participation in the storytelling is required.

Movies made in a filmmaker’s mind and videos made on a monitor have tended to tell stories differently.

- In part because film camera systems had less depth of field than video camera systems, but also because of mind vs. monitor filmmaking, movies tended to have a deeper sense of space and be more dimensional. Videos tended to have a shallow sense of space and be flatter.

- Because of the large size and resolution of film displays as opposed to the small size and resolution of video displays, but also because the scale of the mind is far greater than the scale of a monitor, movies tended to have larger shots held longer so that you can see them whereas videos tended to have closer shots cut faster.

- Movies tended to have greater color depth and palette than videos for the same reasons.

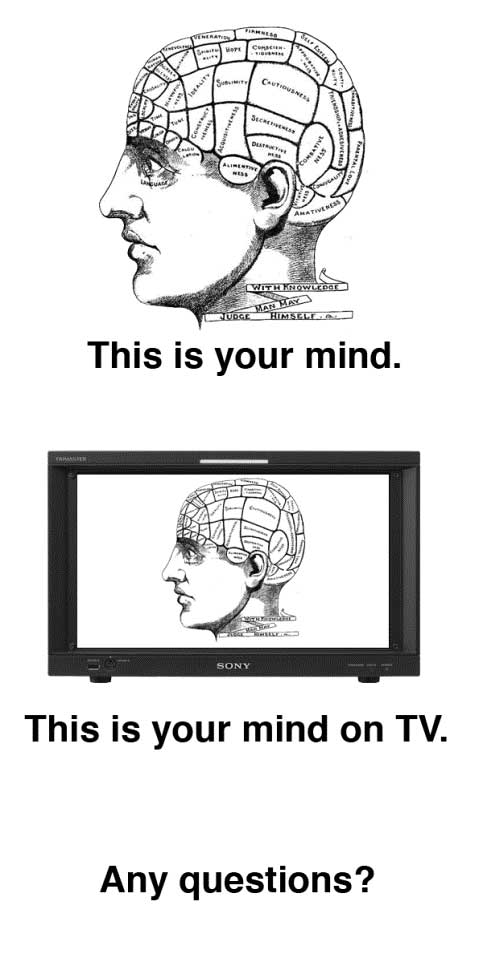

The mind is multidimensional (x, y, z, time, memory, hope, regret…), while monitors are stubbornly 2D. The stories created with each tend to adjust accordingly.

Technology has changed: Film and Video had a child, and its name is Digital. We’ve got big imagers, small imagers, high-resolution displays, digital projection in movie theaters, RAW, log, LUTS, HDR and HFR. We’ve got people trying to pull focus on still photo lenses with cheap follow focuses. At every step of production and post-production, armies of people with computers can touch the image and have their way with it. Some of the viewfinders are very sharp indeed. Everyone has his or her eyes glued to the monitor.

Because the technology that we use to make movies has changed, with monitors at the center of each filmmaking activity, movies have changed: they are more like videos.

More 2D, with thinner stories; less meaningful (even, and maybe especially, 3D movies have 2D stories). Everything is compressed to fit into the tiny bandwidth of the monitors used by the filmmakers.

This is terrible for the poor actors, by the way: an actor wants a human interaction, a feedback signal, some connection with the Director after finishing a take. So, he or she looks up after hearing a muffled “cut!” only to see a circumspect camera operator and maybe the Director’s butt sticking out of the video village tent. Performances tend to adjust accordingly.

However, even though technology has changed a lot, filmmaking hasn’t changed at all: people still have to imagine the story into existence.

The central part of a director or DP’s job is to artfully, gently (and sometimes firmly) lead the rest of the team to tell the story as movingly, as cinematically as possible. The monitor is often this person’s chief antagonist, a seditious malcontent bent on turning the movie into a TV show.

I’ve learned to hold my friends (the team) close and my enemies (the monitors) closer. I’m working hard to be a guy who can make cinematic movies using a monitor. And, even though the damn thing is like a ball and chain (try nipping across the street to catch a shot when the camera’s on a short Teradek leash or attached to an SDI umbilical cord), I’ve learned to stop worrying and love the village.

Here’s some tips for shooting cinematic movies using monitors:

- Block. Light. Rehearse. Shoot.

The Holy Quadrinity, the best practice for filmmaking, well established 100 years ago and never bettered. Ignore the camera when blocking: there aren’t shots yet, only the actors and Director telling a story. The DP and Director design the shots once the blocking is finished. Ignore the monitor most of the time when lighting, This is the more creative portion of the process: use your mind for that. By the time it gets to the camera rehearsal, the story has been mostly created; use the monitor as a tool for adjustments.

- Look with your eyes first.

Stand near the camera and look at the set, the lighting, the actors, the story unfolding. Use your understanding of cinema and your imagination to make the movie. This goes for the Director and the DP, who have more access to the camera, but also, as much as is possible, the DIT, Gaffer, Grip, Art, Props, etc.

- Look at the monitor after the creative work is done.

What is left is tweaking: cables are in the shot, spill from a lamp, etc.

- Show the monitor to everyone.

Hearing a voice call from the video village tent “ok, um, move the flag to your left…” just fetishises the monitor and gives it undue mystery. During the tweaking phase, I try to have a big monitor pointed at the set so that Art, Grip, Electric, etc. can do their own adjustments while looking at it.

- Hire a crew that you trust.

Communicate what you are trying to do, move them with the specific things that are important to you, and let them get to it. Then you don’t have to stare at the monitor, constantly keeping tabs on them.

- Place the monitors in places where they don’t have to be moved much.

This minimizes their impediment to new set ups. Wheels are good.

- Get a DIT

(Digitial Imaging Technician); he or she will watch the monitors (picture, wave form, etc.), taking care of problems so that you don’t have to.

Yes, this requires skilled people. Yes, it requires faith in them. It requires a lot of the entire team: to create a movie in their imaginations, to minimize and handle the technicalities, relax and enjoy filmmaking. But the rewards are better movies that move people. Plus, it is a lot more fun making them.

Don Starnes directs and photographs movies and videos of all kinds and is based in Los Angeles and the San Francisco Bay Area. He owns seven monitors.

Also by Don Starnes:

It’s the Producer’s Invitational Pancake Breakfast. Just as the producers are cutting into short stacks with their plastic forks, all of the doors are locked…

Feature film: first day. The first-time director is 45 minutes late. Finally, he shows up: harried, stubbly, preoccupied and exhausted…

A sign taped to the door says “Quiet– filming.” This only makes you more nervous.

Hint: it isn’t by reading this.

Just in time for NAB, the 9250-XL is everything that a producer could want in a camera. The revolution has begun…

How to make your own digital theatrical ‘print’ using Final Cut Pro, After Effects, guerrilla DCP software, pluck and maybe a little help from your friends.

Skitch a ride up its steep learning curve using my template and tutorial.