Writer’s note – I’ve been accused, in the past, of spoiling the fun for people who design and use LED lighting. Happily, today’s going to be… eh, well, another dose, sorry. But read to the end, for there is hope!

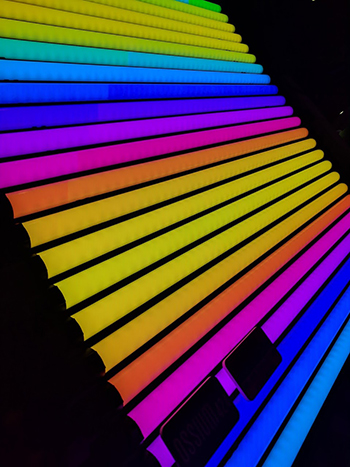

Let’s say that we’ve been through all of the wonderful preexisting coverage of lighting here on PVC, and we know all about the tradeoffs between efficiency and colour quality and how to pick an LED that won’t make the female lead look like Jack Nicholson in Batman. Let’s say that we’re doing something that involves some saturated colour – a nightclub, fireworks display, or, most colourful of all, a night scene involving whatever of blue or green we’re using to represent moonlight this week

So, we gather our resources, including some of the most advanced and capable LED lights available. We scatter them around an expansive outdoor location, connect them all up via wireless DMX and send them all the same hue and saturation commands. It’s a symphony of technology, but if we have three different manufacturers involved, we might see three different ideas of what those hue and saturation commands mean. In 2021, it’s still possible that might even happen if we have three different lights from the same manufacturer

So, we gather our resources, including some of the most advanced and capable LED lights available. We scatter them around an expansive outdoor location, connect them all up via wireless DMX and send them all the same hue and saturation commands. It’s a symphony of technology, but if we have three different manufacturers involved, we might see three different ideas of what those hue and saturation commands mean. In 2021, it’s still possible that might even happen if we have three different lights from the same manufacturer

It’s is a problem that’s actually existed since the 1990s and the advent of variable colour shutters in intelligent lighting. Waving cyan, magenta and yellow flags in the beam of light creates a subtractive colour model that lets us mix colours just as we would with RGB or hue and saturation controls, but if we take several intelligent lights and feed them all the same data – three numbers – they’ll all look different colours.

That happens for a number of reasons. The light source might not be the same colour. The cyan, magenta and yellow may not be the same cyan, magenta and yellow in each case. The amount of cyan, magenta or yellow we get for a given value might not be the same. Similar things pertain with LEDs. Most competent, modern LED lights will have a huge amount of colour processing in their electronics which alone would be enough to ensure that similar hue and saturation numbers won’t lead to similar results even if the LED emitters themselves matched – which they invariably won’t.

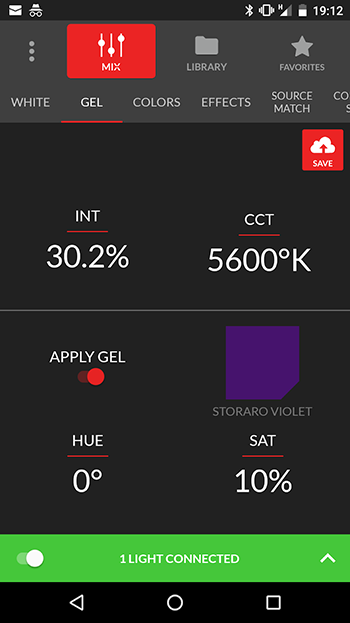

It’s actually as much a conceptual problem, though, as it is technical. There are a lot of ways to specify a colour, but assuming we’re working in hue and saturation, if we set saturation to zero, the light is white and hue becomes irrelevant. That then provokes the question of which white, which is sometimes specified in terms of colour temperature, but then again sometimes not. Hue is an angle, and traditionally zero degrees is red, but which red? One hundred per cent saturation might mean different things depending on the capabilities of the light to create saturated colours, especially if we have a camera-compatible colourspace selected which might deliberately place limits on what we’re allowed to do.

Various reasonable solutions to this have been proposed. Frankly, every light ever made that has multi-channel colour mixing represents at least one proposed solution to this. As so often, what’s important is not so much which solution we choose, but that we all choose the same one. For the sake of comparison, LEDs as a motion picture lighting technology are currently about as mature as light bulbs were in around 1910, so it’s no great surprise that there are some wrinkles yet to be ironed out.

What we’d probably like is to have hue and saturation controls that match between lights, since that’s a reasonably intuitive and familiar way to specify a colour. Lights are increasingly starting to allow the specification of colour in terms of coordinates on a CIE xy chromaticity diagram, which is a nice, device-independent way of doing it, and by the time a device has the ability to do that, offering almost anything else is just a matter of geometrically hopping around the CIE chart. That’s still advanced stuff, though, and there are plenty of quality lights out there that don’t do it. Really advanced colour processing implies a young cellphone’s worth of processing power, though that’s not really too much of a concern any more.

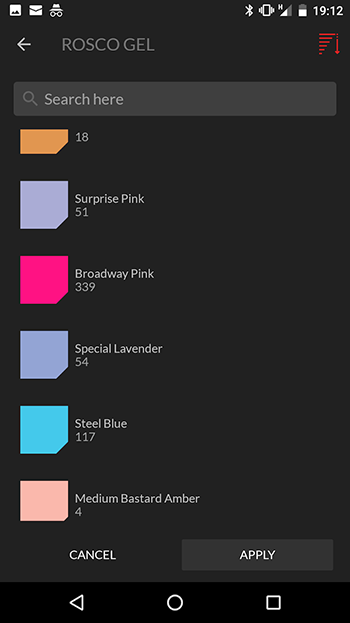

Until those changes roll through, we remain fundamentally dependent on the mark one human eyeball to make lights match. Still, take heart. Wayward, aged HMIs have the same problem, and we can only tweak those using very nearly transparent pieces of plastic sheet, which represent a rather different, if equally precise and demanding, kind of technology. Whether gels really work that well on LEDs is another matter; anyone trying to make even a very good daylight LED into a tungsten one with a bit of full CTO will have noticed that things don’t always turn out exactly as we’d hope but that’s a consideration for another day.

Until those changes roll through, we remain fundamentally dependent on the mark one human eyeball to make lights match. Still, take heart. Wayward, aged HMIs have the same problem, and we can only tweak those using very nearly transparent pieces of plastic sheet, which represent a rather different, if equally precise and demanding, kind of technology. Whether gels really work that well on LEDs is another matter; anyone trying to make even a very good daylight LED into a tungsten one with a bit of full CTO will have noticed that things don’t always turn out exactly as we’d hope but that’s a consideration for another day.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now