Introduction

Once upon a time, videos came on tapes and then discs. And now they mostly don’t. Along that long, torturous journey (remember HD-DVD?) have come huge increases in resolution, clarity, and file size, plus notable failures. High frame rate delivery had a few fans but too many people disliked it; 3D is dead for most of the world; 360° VR video is more likely to be used for capture than delivery. Maybe a new headset will resurrect these in the future, but they’re hardly mainstream today.

Other technologies have succeeded, in one way or another — at least at the high end. HDR video can be seen on streaming services on most phones. Surround sound is standard for many deliverables, and spatial audio, already rolled out to Apple devices (and found on some apps on other platforms) is making surround sound easier to deliver to more people.

But the high end is hardly the only way that consumers enjoy content, and far from the only way that we editors deliver it. While many professionals reading this do deliver HDR content with surround audio to paid streaming video platforms, there are many more professionals (and of course amateurs) delivering to social media, direct to clients, and into countless unusual niches. How can we all push past this flat, stereo 4K SDR present into a great glorious future? Let’s gaze into a crystal ball to see what’s coming next and how we can use it.

Huge resolutions

Resolution increases are one of the easiest improvements to make, but we’ve reached the point of diminishing returns. Cameras today can shoot 6K, 8K or 12K, but given the viewing distance most people sit from a TV, buying a TV with more resolution than 4K is almost certainly an expensive waste of time. Oversampling at capture time isn’t a waste — it allows for strong reframing, zooming, noise reduction, and even stills extraction — but delivering bigger than 4K? I don’t see it being important for a long while.

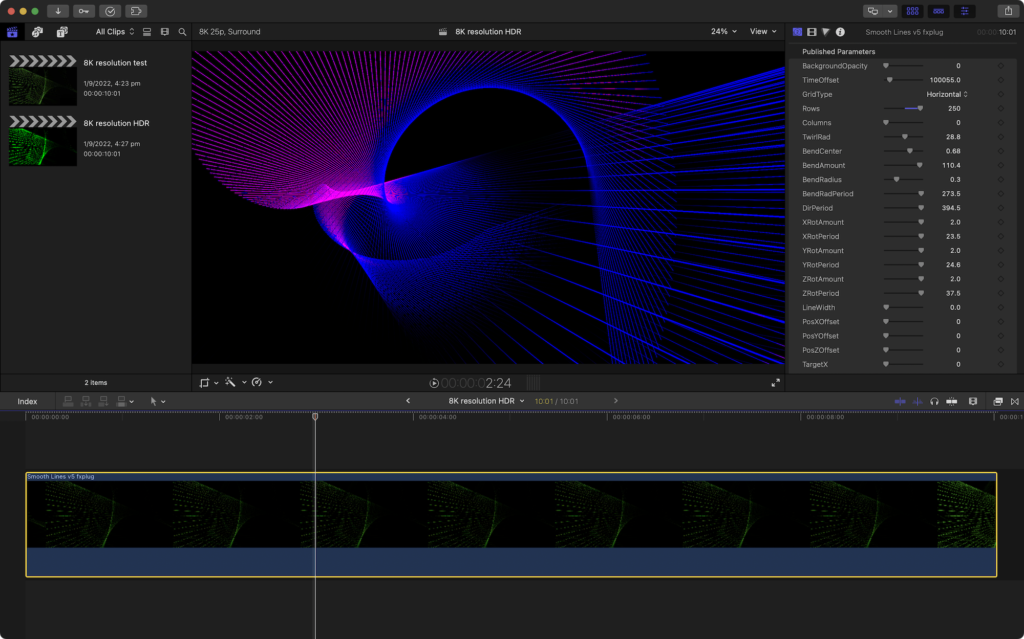

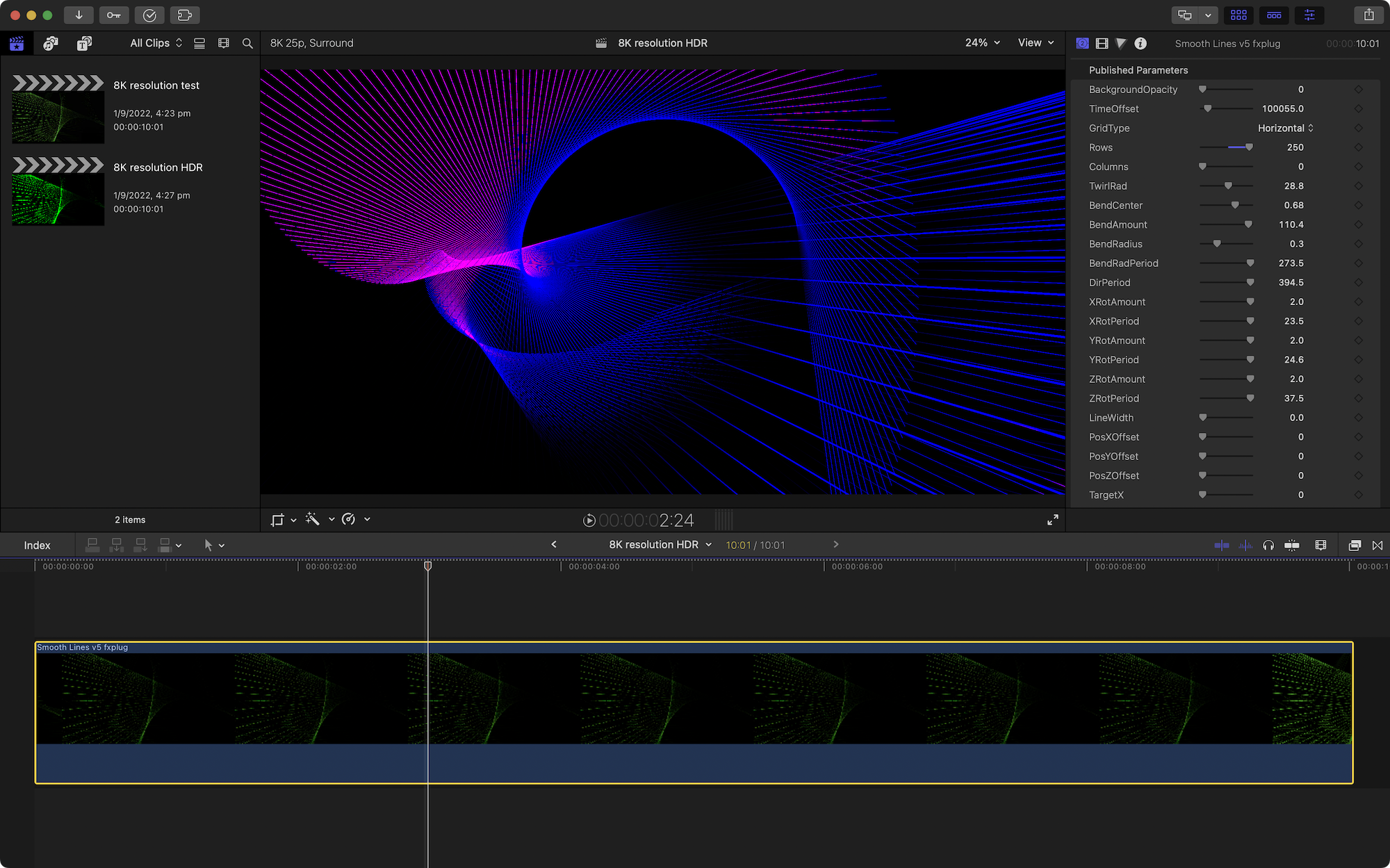

Now, just because you probably shouldn’t bother, does it mean you can’t? No! You can probably edit 8K in your favorite NLE, though the export might take longer than usual and you might need to make some new custom export presets. You can even deliver 8K footage to end-users on YouTube — MKBHD did it back in 2017.

Here’s where we hit a snag. YouTube can take some time (perhaps days) to process the 8K version of your file — I uploaded a test clip days ago that’s stuck at 4K. But when or if the 8K file becomes available, almost nobody has a device that’s actually capable of playing 8K files.

If you’re lucky enough to have Chrome on a fast-ish Mac connected to an Apple Pro Display XDR, or a PC connected to a massive, expensive TV, you’ll see a slight clarity improvement. While 8K TVs are indeed starting to show up, it’s not trivial to connect one to a computer. Macs currently top out at 6K, and you’ll need a fancy GPU on a PC to get there. Here’s a YouTube search to get you started.

After all that, you’d have to stand uncomfortably close to it to see any extra detail over 4K. There are still many cinemas projecting in 2K, and while you and I may notice the quality difference vs 4K, many people don’t. But don’t make the mistake of thinking that resolution isn’t important at all. (Exhibit A: the only streaming service in Australia that shows House of the Dragon and other HBO shows is *still* limited to 1080p.)

Weirdly, the difference between 1080p and 4K is far more obvious on a 4K desktop computer display — you’re close to it, and you can see the extra detail. Modern 4K YouTube videos look great and (if you’re paying attention, have decent eyesight, etc.) are noticeably better than 1080p videos. This is at least in part because YouTube uses a better codec, as well as more bandwidth, for 4K content over 1080p content — here’s the proof. 4K is a no-brainer today. 8K, not so much.

So — you can, but should you?

While there will be occasions like trade shows (large screens, close up) where you may be able to justify the hassle, there’s not yet a lot of point in delivering at larger than 4K. It’s entirely possible, but nearly pointless.

360° VR

VR video sounds great — record video in every direction around the camera, so that the viewer can look wherever they want. It’s been out for a while, and most NLEs support it. There are a wide range of consumer and professional cameras out there, so, why not jump in? Unfortunately, technology hasn’t quite improved to the point where 360° video works well enough.

The first problem is that there aren’t enough headsets out there, and when they are used, they aren’t used for very long. If Apple can nail this problem, then maybe that hurdle goes away, in time. But that leads us to another problem: if you are using a headset, you’re only looking at a tiny part of the frame, and the resolution just isn’t big enough to look good. Many cameras are barely 6K, and videos are often delivered at 4K.

But your eyes don’t see all of that, because you’re looking at around 25% of the frame at any one time. With only 1000 pixels or so, it looks pretty blurry, and we’d need a source of 8K-12K for it to look good — it’s just not feasible to deliver proper VR video just yet.

Even with a magical future headset with fantastic resolution and a network to deliver it, you’re still left with the problem of how to tell a story. In 360° video, it’s difficult to hide edits, difficult to hide the crew, and difficult to know where people are looking. Probably the worst thing of all — if you move the camera at all, you’ll make a large proportion of headset viewers sick.

Today, 360° cameras do have uses, but largely in virtual tours (still images look much better than videos) and for reframing for standard flat delivery. The great joy of a 360° camera is that you don’t have to point it at the subject, and gyros keep them incredibly stable. Terrific if you need a quick wide angle or you don’t know quite where the subject’s going to be.

Once again — you can, but should you?

As much as I really do like 360°, probably not for general purpose, professional work — though you might be able to sneak in a quick ultra-wide or tiny planet shot for variety. Outside of specific, niche projects, 360° is better as a home video or social media tool.

HDR and/or wide gamut colour

Instead of more pixels, HDR makes each pixel better — potentially brighter and more vibrant. Instead of crushing brighter areas into the standard dynamic range (like HDR photos do) HDR for video expands the range of acceptable brightness levels and the range of colors available. Many modern screens are capable of wide color gamuts, and a large chunk of those — including most recent iPhones and the latest MacBook Pro screens — are HDR-capable too. HDR is something we can deliver for a wider range of content, not just for features.

Looking for some nice examples of HDR you can actually download? Sol Levante [watch here https://www.netflix.com/title/81017017 ] is an experimental anime from Netflix that pushed a few boundaries back in 2020; it’s in 4K HDR Dolby Atmos. There’s a full production breakdown, and the team have made their image, video and audio assets downloadable. Thanks, Netflix!

Assuming you can see HDR content yourself, your NLE of choice will be ready too. FCP and Resolve handle HDR color management well, and Premiere is on board if you follow these instructions.

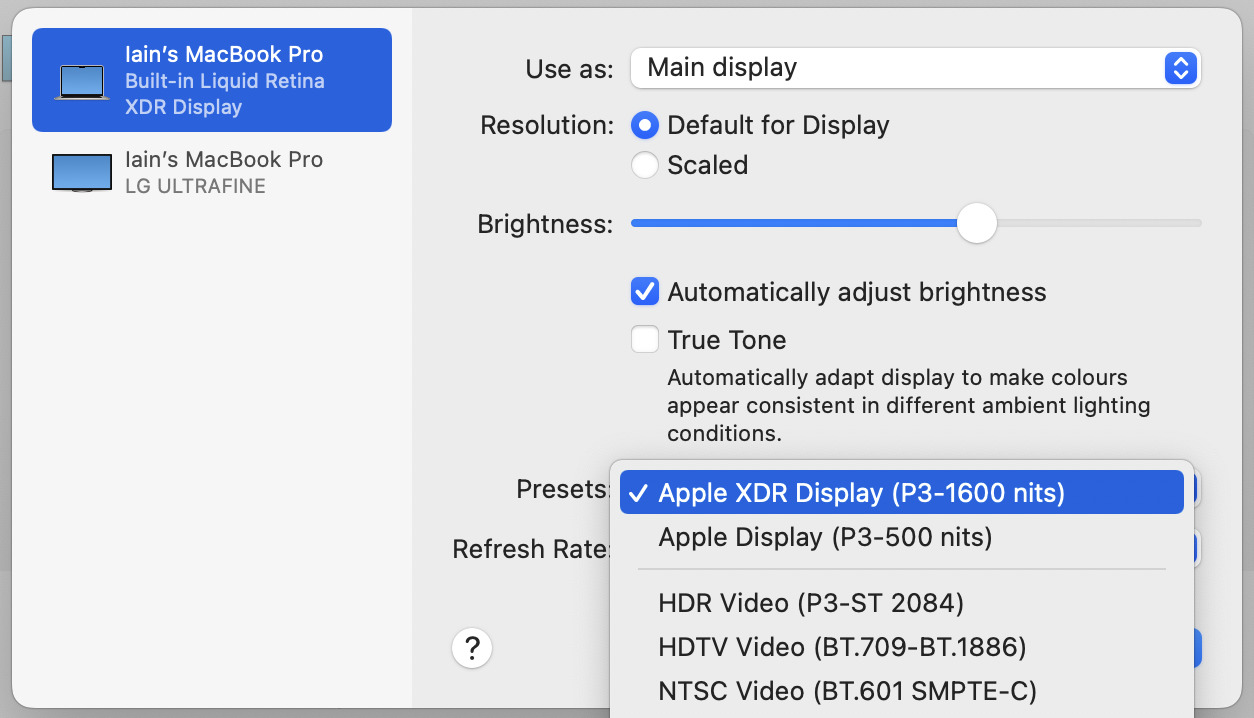

Remember the standards confusion with SDR video? While there are issues around brightness display of standard SDR videos, current standards are fully prepared for HDR. In theory, it should be easier to deliver the same video to everyone’s eyeballs, but display differences make that yet another mirage. The standards may be explicit about how an HDR video should be tagged, but different devices have different capabilities in terms of maximum brightness, peak brightness and color gamuts.

Some monitors and TVs can go to 1000 nits (AKA cd/m2), but others only 400 nits, and there are (of course!) two different standards with different ideas about how to manage brightness levels. HLG grades brightness on a curve, so the top end of the brightness range matches what your device can offer, even if it looks a little different between displays. PQ makes an assumption about the maximum brightness level (10000 nits) and can theoretically deliver the same content to different displays, so long as the brightest part is within spec. Conveniently, the BT.2100 standard encompasses both, so use whichever works.

If you want to get even fancier, there’s also Dolby Vision, which adds dynamic metadata to help a display to get each scene right. If you’re watching this on a streaming service, Dolby Vision is similar to PQ, but the version used on the iPhone is HLG-based.

Another issue is that it’s not always straightforward to precisely control how an HDR video will appear on an SDR screen. Given the issues around color consistency on SDR displays, this may not come as a surprise. Because not every delivery platform understands HDR, and because not all devices understand HDR, it’s not always possible to deliver one file for everyone. Sometimes at least, you’ll need to provide an SDR and HDR master, and each needs a separate color grading pass.

If you’re lucky, you may be able to deliver a single HDR video, and rely on the platform to create the SDR version for you. To make the downconversion to SDR match your expectations more closely, you can provide YouTube with a conversion LUT, following the instructions here.

If you don’t want to grade twice, just cross your fingers instead.

Note that it’s possible, though a little unusual, to use Wide Gamut color without HDR brightness levels. Unfortunately, without an HDR transfer function, YouTube will convert 10-bit wide gamut color to 8-bit. You might as well jump all the way to HDR if you’re pursuing wide gamut color.

Support on other platforms is both spotty and still in flux. Vimeo does support HDR uploads, but their SDR conversion didn’t look exactly the same as YouTube — watch for subtle differences here. As with YouTube, processing can take a while. At the time of writing, an 8K HDR video I uploaded to Vimeo yesterday is still processing, so I have an HDR video with vibrant, bright colors (yay) that I can view in glorious 360p (boo).

Instagram has apparently allowed some people at least to post 1080p60 HDR videos, but I’m having no luck making it work myself, and there’s no mention of HDR in their online help. Facebook doesn’t seem to be able to handle HDR video either. TikTok is a dumpster fire for professional content, HDR or otherwise.

So — you can upload HDR to YouTube or Vimeo, but should you bother?

Sure. If YouTube is a primary delivery method, you might as well make your videos stand out a bit more for a reasonable and growing chunk of your audience. Make sure you don’t degrade the experience for your SDR audience, but a lot of people can see HDR these days. Social media will catch up eventually.

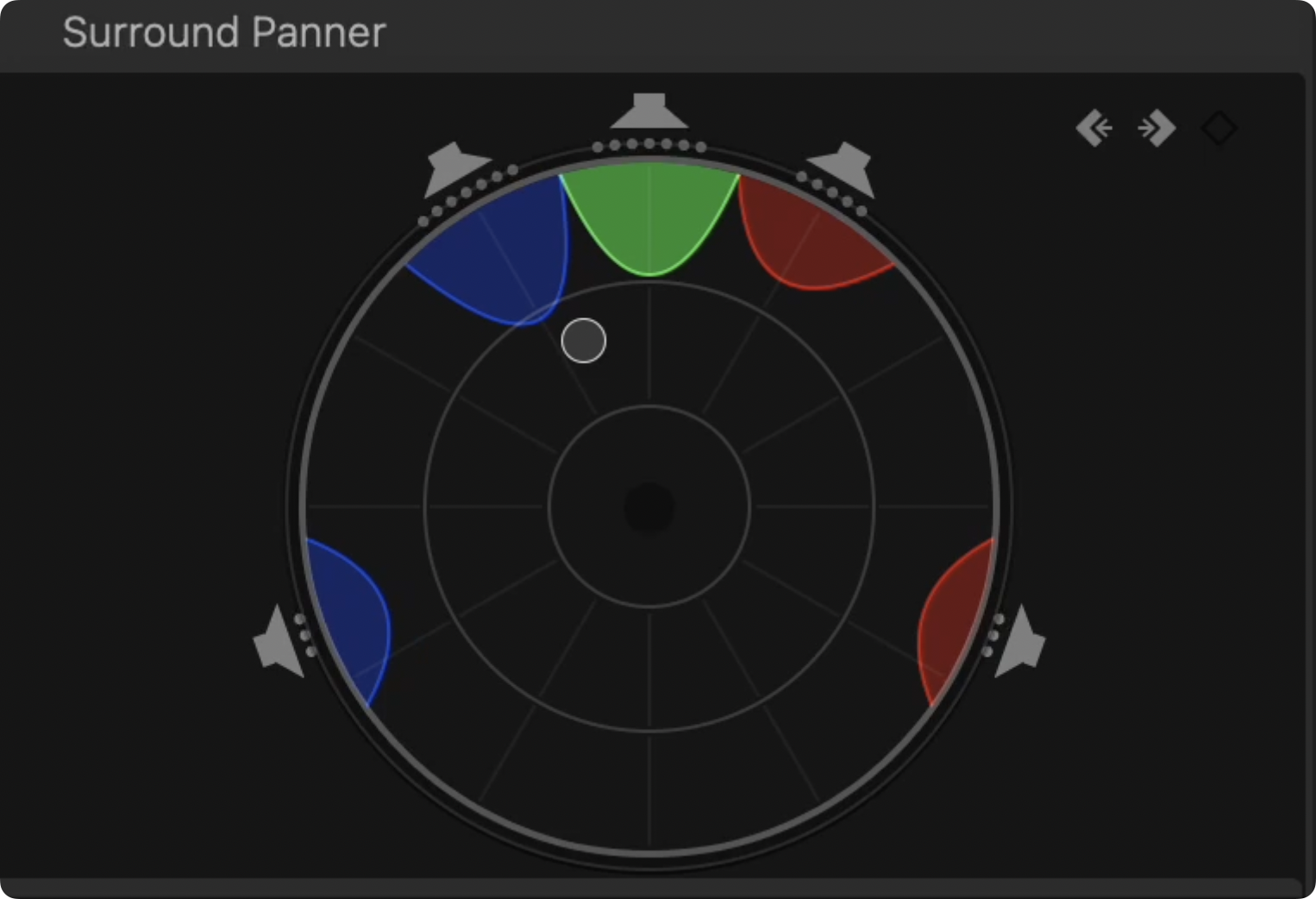

Spatial Audio, or even just 5.1 surround

Spatial Audio can mean a few things. It’s used by Apple as their new term for fully immersive sound in headphones, but it’s also used (generally without Capitals) as spatial audio, to mean “better than stereo”. In a cinema or a home cinema, this usually means Dolby Atmos, the industry’s current standard way to deliver omni-directional audio.

Here’s a behind-the-scenes of the previously linked Sol Levante short.

In practice, you can definitely hear the difference between stereo and surround content through headphones; surround is more immersive, even if some of the finer details, like vertical positioning aren’t as clear as they could be. Anything better than stereo is a huge step up, and I’ll take it. With the latest macOS, you can experience spatial audio through your Mac speakers or through connected Apple headphones, and it’s not a subtle change. It’s a massive improvement, and in many ways it’s more obvious through good headphones, because you’re in the perfect listening position and can’t hear anything else.

Even though I’ve had a Dolby Atmos setup at home for years now, and there’s been plenty of Dolby Atmos content for years too, it’s rare that surround audio is truly noticeable. The combination of the low audio levels that the rest of the family will tolerate, and the fact that many sound mixes just aren’t that exciting, means that action blockbusters are the only ones pushing the envelope here. Because so few people outside of cinemas have had the option to go beyond stereo, it’s not been a problem, but with Spatial Audio on every Apple device, we should be doing better.

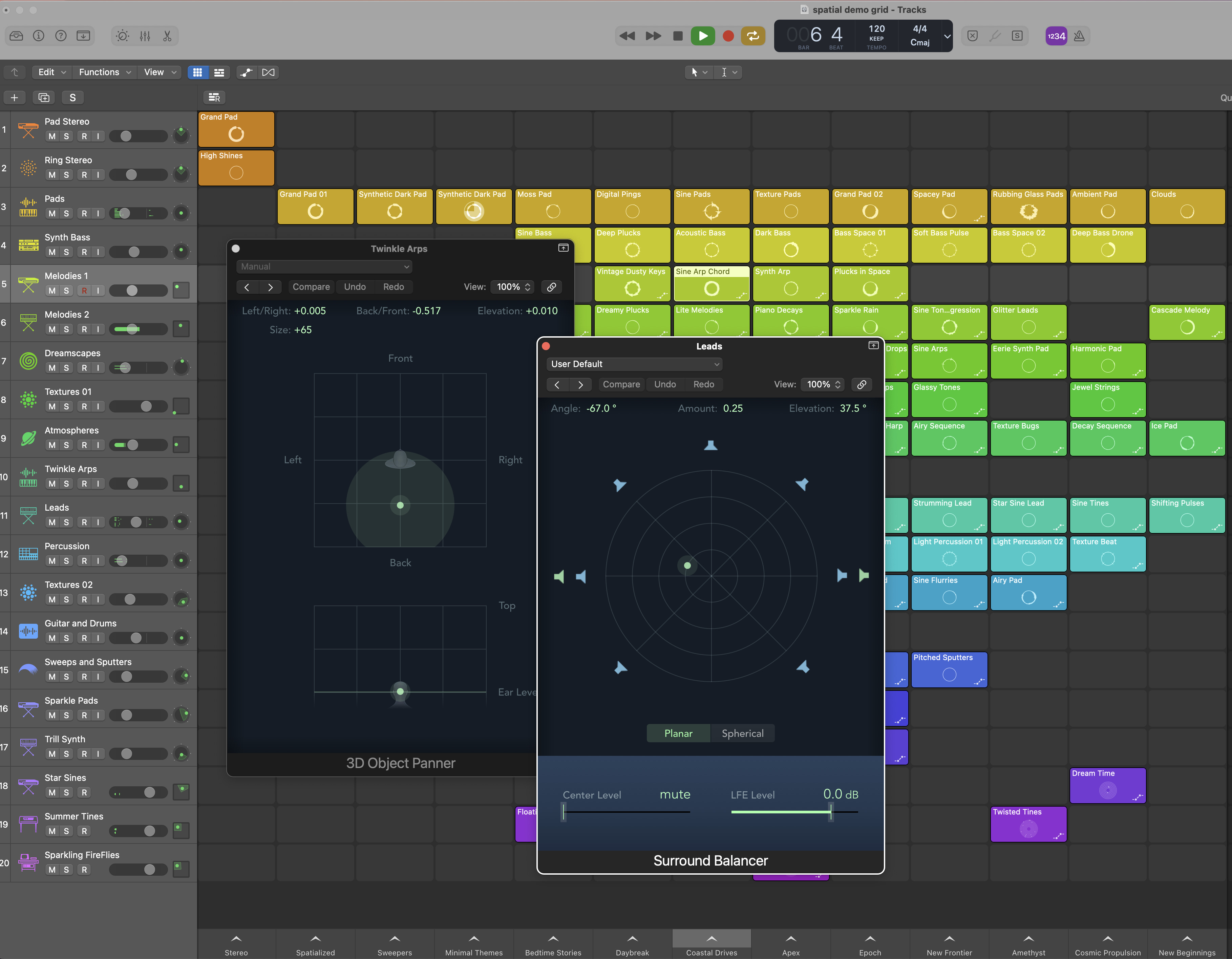

If we accept 5.1 as “good enough” then you’ll find support across most NLEs, and with the latest Spatial Audio support on macOS, if you’re an FCP user with fancy Apple headphones, you can actually listen to surround sound live on your timeline. Of course, if you want to get really serious, then you should move the mix to a DAW like Logic Pro where you can embrace the full Dolby Atmos experience with proper mixing controls.

So, it’s possible to create surround sound — can you deliver it to anyone? This is a more thorny problem. Vimeo doesn’t allow surround but converts to stereo on upload. YouTube doesn’t allow surround uploads for regular human creators but does allow 5.1 for Studio-level creators and does allow spatial ambisonic audio for 360VR uploads. The tech is there, but it’s not ready for regular humans just yet.

Surround sound support is coming to all mobile Netflix users soon, so there’s hope that consumer demand will build to the point where YouTube can deliver surround with regular videos. For the moment, only higher-end streaming services are able to deliver on a wide scale. Still, if you can get a file directly onto a Mac or iPhone, skipping the platforms, you can deliver surround sound today.

So — you can make surround sound, but should you bother?

Sadly, unless you can deliver those files directly to your clients, probably not. Wedding videographers could probably deliver some great mixes, though. As soon as YouTube flicks this switch, get into it.

High frame rates

Douglas Trumbull (director of the 1970s classic Silent Running) was a fan of higher-than-normal frame rates, patenting a 70mm 60fps system called Showscan. It never went mainstream, but in recent years, given the capabilities of modern cinema projectors, there have been more attempts to move cinema beyond 24fps.

The Hobbit was famously shot at 48fps, but it would be fair to say that it wasn’t a hit with most cinemagoers. Billy Lynn’s Long Half-Time Walk and Gemini Man were shot at 120fps, but very few people got to see those films that way. For those that did, it was similarly polarizing.

While it may be true that footage shot at higher frame rates can look more like real life, that’s not necessarily helpful when you’re trying to suspend your disbelief. High frame rate footage looks more different to “regular” footage than any of the other technologies we’ve looked at here. Because of the same temporal rate (albeit interlaced) is used with live TV, it’s especially associated with soap operas and live sports, and to many viewers, feels like the opposite of a movie.

But some viewers really do prefer this smooth look. Today, 60fps is actually common in the gaming world, where modern shooting games need as many frames as they can get their hands on. Dedicated gaming displays can go beyond 360Hz, and modern iPhone and MacBook Pro displays can display 120Hz. Modern cameras can handle high frame rates too, but most cameras make some kind of sacrifice to do so — in resolution, or color fidelity, or dynamic range, or compression quality. Still, some YouTubers have embraced 60fps, but most have not — it remains a controversial choice.

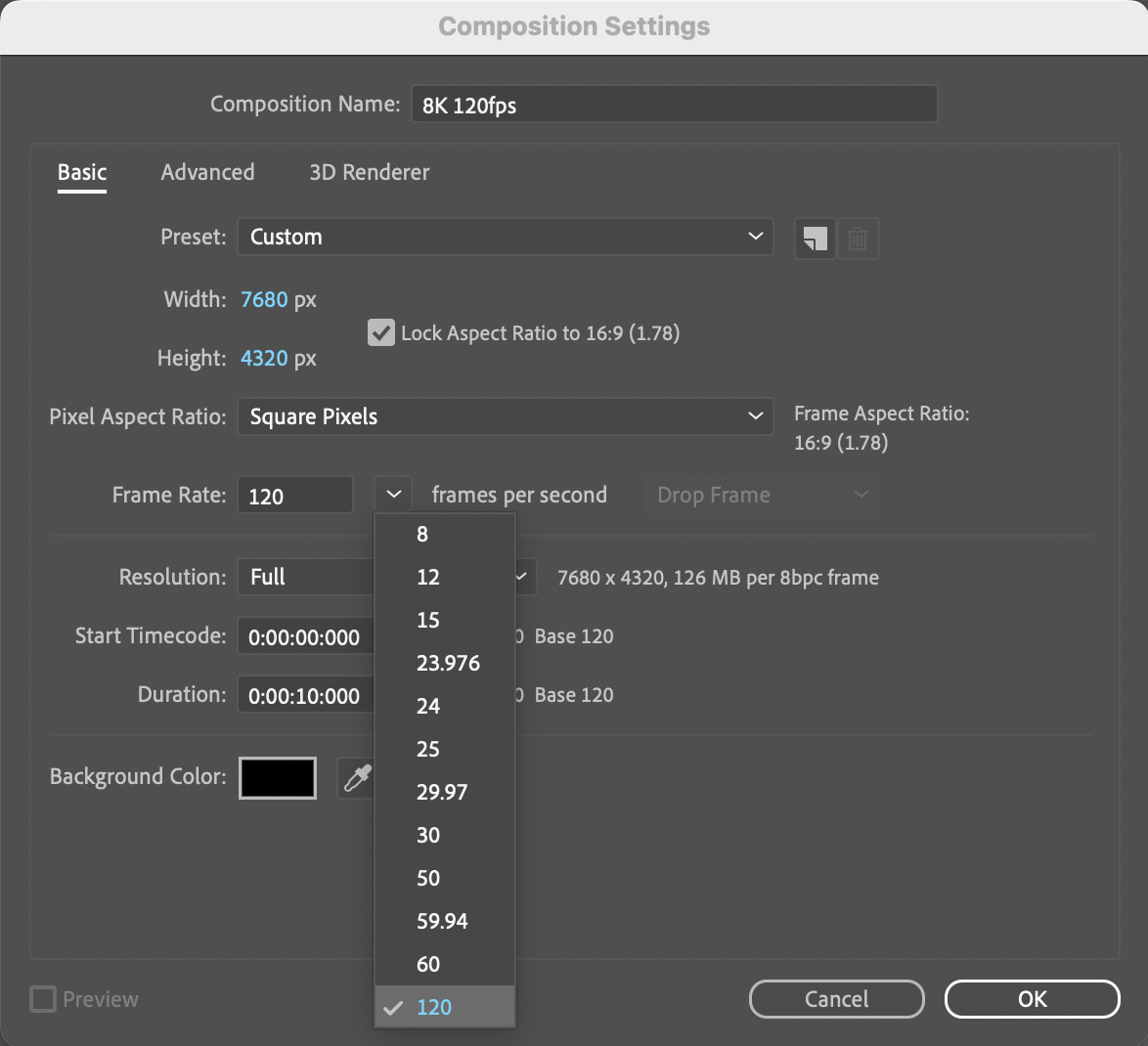

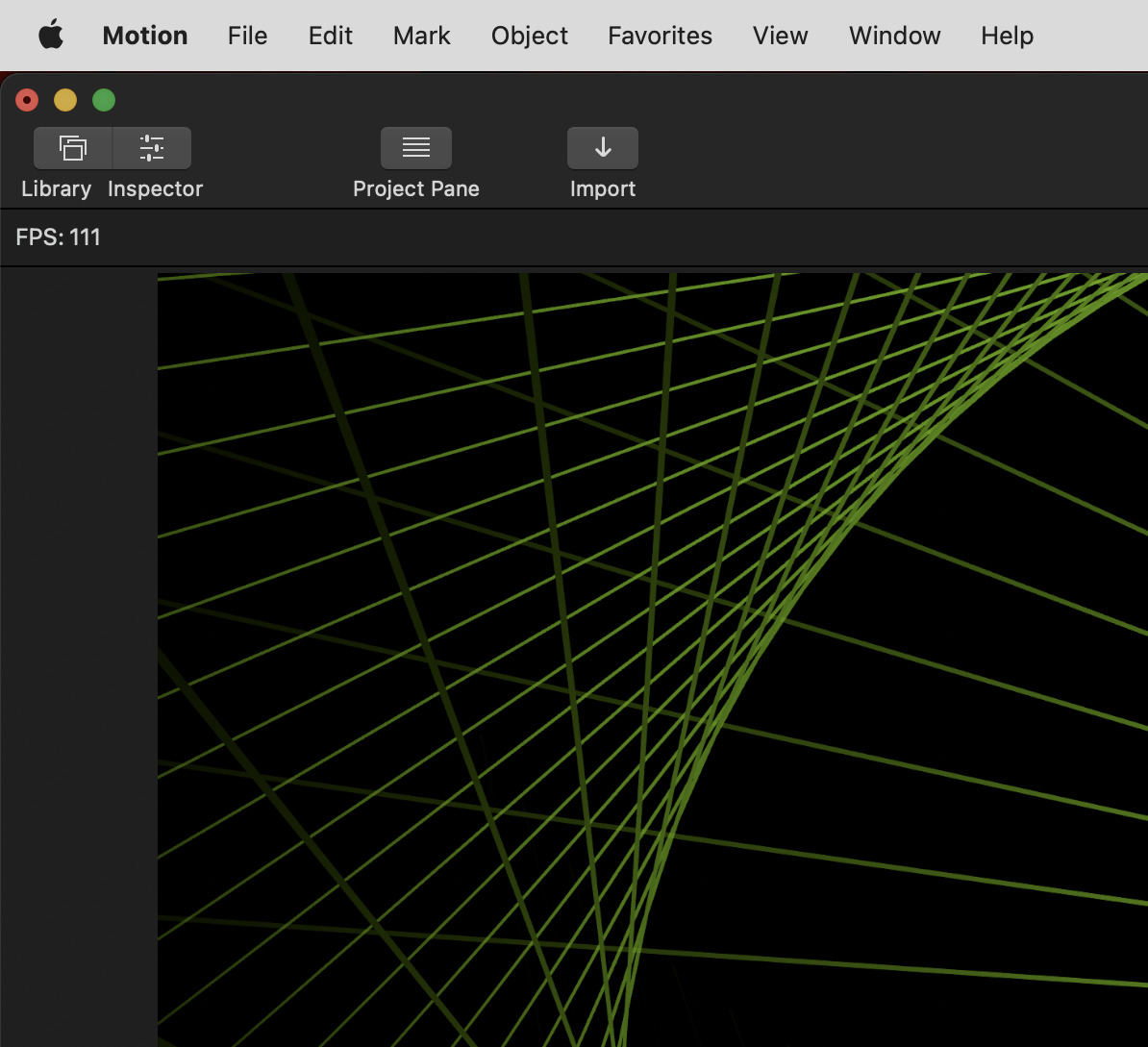

All modern NLEs can handle 60fps, but support for 120fps is less common. Resolve is on board, and After Effects and Motion can both handle 120fps, but Final Cut Pro and Premiere are limited to 60fps. Still, even if you can edit at 120fps, you’ll struggle to show anyone.

YouTube and Vimeo top out at 60fps, so those higher frame rates remain tricky. If you have an iPhone 13 Pro or better, you can select Slow Motion and actually see 120fps live on your device — try it, it’s something new. Plus, if you have a capable screen and any camera that’s capable of 4K @ 120fps, you can edit in AE or Motion, but they will likely struggle to handle all those pixels at once. After exporting, you’ll see the full frame rate on playback, but you may need to tweak things.

QuickTime Player will presume to think you’re watching slow-motion footage, and will slow it down until you adjust the retiming controls to stop that happening. Instead, use FCP if you can — it can cope just fine with higher frame rates for source material. Premiere and Resolve worked too, but were a bit jumpy. Sadly though, the content will need to move pretty quickly to look much different from 60fps.

So — you might be able to shoot and see 120fps. Should you?

Probably not for narrative projects. Higher frame rates have been pretty unpopular for most deliverables and most audiences, but it could work well for specific purposes like theme park rides.

Conclusion

The lowest common denominator shouldn’t be your top-end target, and just because broadcast delivery standards are stuck in glue doesn’t mean you can’t surpass them for at least some of your audience. Screens are getting bigger and brighter, sound is becoming more immersive for more people, and not every job is seen on a phone. If you want to impress the people who’ll bother to watch your work on a big screen, make it look as good as it can.

Plus, now that we’ve moved beyond physical formats it’s going to be easier to improve standards, so don’t be afraid to push at those boundaries. As consumer technology improves, we’ll be able to deliver new kinds of videos, and if you’re ready at the bleeding edge, you can be first out the gate when your clients need richer content for their new toys.

Still, it remains to be seen if the combination of higher resolutions, higher frame rates and more immersive audio create something totally new, or just something a bit nicer. It’s going to be fun either way, but until we get a holodeck, I’m not going to be satisfied.

Further reading and viewing

The pros and cons of 8K UHD video resolution, from Adobe

https://www.adobe.com/creativecloud/video/discover/8k-video.html

A 24fps Filmmaker Reacts to Gemini Man in 120fps

https://youtu.be/OaZnxAfcvY4

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now