Previously, we explored how the invention of monochrome video tape and the FCC’s approval of RCA’s compatible color television system came together in 1958 and were able to capture what is still the most honored single program in television, “An Evening with Fred Astaire.” The show won nine Emmy Awards, a record that still stands in the annals of the Emmy Awards.

Then, thirty years later, it won a tenth award for the technical excellence of the restoration of the show. It is the story of the restoration we’ll concentrate on this time as well as pay tribute to the man who, not only was the one primarily responsible for making the restoration possible, but also one of television’s most devout historians – Ed Reitan.

The Astaire show restoration was performed under the auspices of the UCLA Film and Television Archive. The 10th Emmy was presented to Dan Einstein, Television Archivist of the UCLA Archive, along with Ed Reitan and Don Kent as well as to the Archive inself. It was Reitan who did the in depth technical work required to resurrect the unique color video tape format of the program – no small feat!

Unfortunately, as I began preparing these articles, Ed Reitan passed away. It was a sad loss for early television preservation. Besides understanding the obsolete technical systems used in television’s early days, Ed was also a historian of the industry. Some of his extensive research and historical data can be found on his website, now supported by the Early Television Foundation and Museum. But it was his ability to match the old with the new, such as the work he did on the obsolete two inch quadruplex tapes for the Astaire special that made Reitan unique.

I reached out to Dan Einstein and Don Kent. Kent was quick to credit Reitan’s responsibility in making the restoration possible. The videotape format they were faced with restoring was never part of the design of any machine. Instead, it was a one by one modification to a few of the original Ampex monochrome video recorders purchased by NBC. Those machines were prototypes themselves having been built by hand as part of NBC/RCA’s initial order at the 1956 National Association of Broadcasters Convention in Chicago where practical video tape recording was unveiled. RCA’s Color Television Tape machines would come later after mutual design and licensing agreements were in place with Ampex Corporation.

In my discussions over the last few months with Don Kent a lot of questions were answered, not only about the restoration of the Astaire show, but also information about just how “live” the show was as well as how other programs benefitted from the desire to revive the Astaire show to its original glory.

Up until 1988, the only way to view “An Evening with Fred Astaire” was through a black and white kinescope recording (film shot off a television screen). Dan Einstein told me back in the mid eighties when the UCLA Archive Motion Picture Preservation Program was in initial discussions to begin preserving television programs, the staff met to brainstorm and come up with an answer to the question “What is the one show that stands out?” The consensus was “An Evening with Fred Astaire.”

The search was on. First, they needed to learn if the videotape even still existed. Einstein contacted Astaire’s agent who wrote him back indicating the project was one of Astaire’s “favorite things of all the ones he’d done.” Einstein was pointed to the archive at Universal Studios. Einstein believes that at one time in the sixties there had been interest by Universal to restore the show for broadcast. Astaire’s production company, Ava Productions, owned the show. So he was free to move the tapes wherever he wanted. With Astaire’s blessing, UCLA obtained the tapes from Universal.

In fact, Einstein adds, “We received encouragement and support from Universal, NBC and Mr. Astaire. In addition, KTLA should be singled out [for their support] because they allowed us to come there on nights and weekends and use their equipment at no charge.”

The natural next step in resurrecting the show was to get the tapes to playback as they originally looked back in 1958 – or better, if possible. To do this, Einstein took the tapes back to where they were made in the first place. At that time, NBC still had a two inch quadruplex machine that would at least play the tapes. According to Don Kent the machine was probably an Ampex VR2000, the successor to the original prototypes and the VR1000. NBC had used it for reproducing tapes for their 50th Anniversary show and occasionally still had the need to play some of the older tapes. That is probably the machine UCLA attempted to use for their initial pass. However, the results were less than satisfactory.

About this same time (1985), Don Kent was working as a tape engineer at KTLA in Los Angeles. He came to Dan Einstein looking for tapes of the Ernie Ford Show, another NBC show recorded about the same time as the Astaire show. Kent’s father had appeared as a regular in the show and he was collecting as much material as he could of his father’s appearances. Separately, Kent later recovered some of the tapes of the Ernie Ford Show and took one of them to NBC to be played back on that same machine. He described the results as “very soft.”

According to Kent, during the visit, Einstein showed him some of the equipment they were restoring and introduced him to Ed Reitan.

Ed Reitan was a graduate of UCLA and still lived close to the campus. Although Reitan was employed by ITT-Gilfillan, a US defense contractor, he volunteered his spare time to work on UCLA’s vintage television equipment archive.

At some point, the subject of the Astaire show came up and how the results of the playback at NBC had been less than optimal. Kent made it known he had access to an Ampex AVR-1 at KTLA, a quad machine that seemed to be able to play anything thrown at it, even tape without a control track.

Unfortunately, the first passes on the AVR-1 weren’t all that good, either. A lot of break up.

Enough of the video came through in color to give Reitan encouragement that a way could be found to make it look as it did in 1958 – possibly even better. From video courtesy of Don Kent.

Ed said he’d do the research on what the technical needs were to properly restore the show if Don would supply the machinery.

“I learned he (Reitan) was able to diagnose the unique electronics of what Ed called “RCA Labs Color,” the modification made to the original Ampex black and white machines so they would record and playback RCA’s color standard,” Kent recalled. To do so, Reitan sought out the RCA engineers who were instrumental in the conversion of the Ampex machines to accept, record and playback the RCA compatible color system.

Although RCA Laboratories no longer existed after being handed off to SRI International as part of the breakup resulting from General Electric’s takeover of RCA in 1988, Reitan was able to find Dalton Pritchard and Roger Thompson in retirement at their homes in New Jersey. Then the revelation he was hoping for. One of the engineers not only had kept the designs for the Ampex modifications in his den, he was willing to make copies and send them to Reitan.

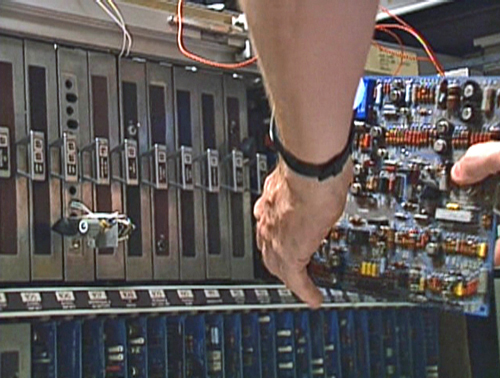

From those specifications and drawings, Reitan fed information along with specifications for the AVR-1 into a computer at ITT-Gilfillan. The resulting design was then etched to several printed circuit boards and populated with the proper components. Kent recalled that Reitan modified at least ten boards used in the AVR-1.

“The current KTLA machine had to remain operational at all times as some two inch quad was used up to the early nineties,” Kent told me. Fortunately, there was an AVR-1 available that had been retired by the station. The boards the group modified came from that machine. When Reitan and Kent replaced the factory printed circuit boards with the modified boards, they loaded the Astaire tape and hit play. The video locked up. No adjustments were necessary. It just worked.

Modified circuit board being installed into Ampex AVR-1. Courtesy Don Kent

The live material was a master recording made at the time the program was broadcast for the eastern United States. The recording was meant to service the west coast time zone feed and was played back three hours later. However, Reitan and Kent immediately saw there were some problems of a generational nature with the dance numbers and the commercials. It was because they were not part of the live program. They had been pre-recorded and “rolled in” to the live program.

What Reitan and Kent encountered would not have been seen by the viewers in 1958. The entirety of the program was considered broadcast quality for its time and for the machinery used to play it back. It’s a situation where advances in equipment over the years became less forgiving of tape errors earlier machines were able to tolerate.

Even though they had been able to resurrect the master material, anything that was a copy from that era presented a problem due to a conflict between two of the frequencies used – one for sync and the other for the color subcarrier. That conflict resulted in shaky video from the AVR-1. As a result, the team had a double problem. They’d solved the first one – The RCA Color Problem. But solving the second one, the frequency mix problem (known in engineering parlance as heterodyne) proved more elusive.

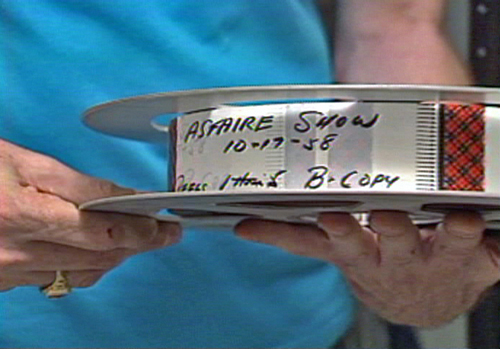

Kent says that’s where the additional tapes come into play. As they went through what had been delivered from Universal, they found “roll-in” reels. On those reels were the master recordings of all the dance numbers.

Don Kent holds one of the roll-in reels for 1958’s Fred Astaire program. Courtesy Don Kent

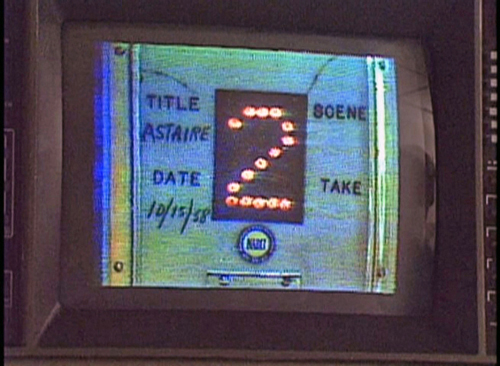

“Astaire would not make the show unless he could pre-record the dance numbers,” Kent said. The slates on the material indicate that at least some of them were recorded a couple days before the show air date. This may be one of the sources for the speculation on the Internet the show was the first one to be PRE-recorded before its airdate.

Slate from one of the roll-in’s for “An Evening with Fred Astaire.” Note the record date is two days before the live show. Courtesy Don Kent

Also “rolled-in” to the live show were the Chrysler car commercials. Since the movement of the cars had to be orchestrated and perfectly timed, the commercials were pre-recorded, too. The material suffered from the same problem the dance numbers did. It was obvious the commercials were not live either.

As an aside, the commercials have a little bit of production lore attached to them as well. It seems that in order to accommodate the ramps the cars use to pass in front of the camera, the lighting grid for one of the NBC Burbank studios had to be raised ten feet to accommodate the wide shot required.

The light grid in this NBC Burbank studio had to be raised ten feet to accommodate all the new Chryslers.

Now that the group was able to playback the tape(s), what recording media should they use? Digital tape had been invented a couple years earlier in 1986 with the D-1 tape format. Sony’s new D-2 digital format had just been released as they were working on the Astaire restoration in 1988, but hadn’t been put into general use yet. Kent says Universal Studios, who was paying for the project at this point, was able to get one of the first D-2 format machines from Sony. He knows this because the serial number on the machine was TWO! Kent adds, “what we had was, at the time, the oldest videotape format being copied to the newest videotape format.” Fortunately, as D-2 was trumped by newer digital formats, UCLA had the foresight to copy the D-2 master to the DigiBeta format.

The Sony D-2, serial number 2 recording the output of the modified Ampex AVR-1. Courtesy Don Kent

Between the dance number pre-recordings and the commercials replacements, just getting the show onto digital became only one piece of the puzzle to be put together. Once the materials had been satisfactorily transferred to digital tape, a week of editing was scheduled at the old Trans American Video post facility on Vine Street in Hollywood.

Kent says, “The hard part we had was with the sound on the transitions between the roll-in’s and the live show. There was background music going on… The audio from the roll-in would start while they were still trailing off the music [from the previous scene]. [That music] wasn’t on the roll-in’s and we had to make a cut to get into the roll-in. But we finally made it match up after seven or eight times. It was just trial and error.”

Even then, there was still some work to be done even after the editing. For the CBS repeat, there was a different sponsor. It seems someone, probably involved with the change of sponsors, had erased Astaire’s audio referring to Chrysler in a portion of the audio track on the master. Now the group had to take the project to an audio post facility. But first, they needed to find the missing dialog with adequate quality to cut in. More research was undertaken. They found the material on a 33 and 1/3 RPM (revolutions per minute) vinyl audio recording of the show. It was released shortly after the original airing and included the missing audio. The copy they found was very clean and the quality was good enough so they were able to match the segment with the rest of the audio track at an audio post facility and “fix” the gap of audio drop out.

The result speaks for itself. Early NTSC color looking its best from RCA TK-41 cameras that had been finely tuned. Videotape color that was believed to be better than the specification to come from the SMPTE for Low Band Color. And another Emmy for the show awarded thirty years after its initial broadcast. And the show even aired again for the first time in decades on the Disney Channel.

After the successful restoration of the Astaire program, Einstein, Reitan and Kent worked together on another color television resurrection and today it is the oldest color videotape known to exist. It was the dedication of the NBC/WRC-TV facilities in Washington, DC, on May 22nd, 1958, six months before the production of Astaire. It is also historic in another way in that it is the first time a US President (Dwight D. Eisenhower) was photographed using color videotape.

Since it used the same video tape recorder color modification as that used on the Astaire show, they figured it would probably be pretty straightforward. Not so according to Kent. “The copy we received from the Library of Congress had more problems than you can imagine.” The problems stemmed from attempts to get the tape to play on too many occasions and failing because they didn’t have the correct electronics. And as far as anyone knew, this was the only copy. However, during the recording, Robert Sarnoff says to President Eisenhower, “We will provide you with a copy of this recording.” The group made note of this and, sure enough, Einstein tracked that copy down at the Eisenhower Presidential Library in Abilene, Kansas.

The folks at the library had no idea what they had and no one had ever attempted to play it back. Kent said they received the tape in a “nice oak box with blue velvet… and it still had the original tie down tape which I got to break after thirty years.” He then added, “It was perfect.” No problems other than some dropout that was recorded in to the tape and an audio dropout that occurred due an error by AT&T Transmission during the recording.

In those early analog network days, the video circuit (the coax) traveled via a separate route apart from the audio circuit (usually a balanced telephone line) – there was no embedding of audio with the video like we have now. A switching error temporarily caused the audio to be reduced in frequency response so it sounded a lot like a telephone call. The group did their best again at making it sound better, but, as Kent says, “there just wasn’t that much to work with.”

The reason AT&T transmission was needed is that the recording was being made 3000 miles away at NBC in Burbank possibly because those were the only color tape facilities available across the network. At that time, the primary use for videotape was for time zone delay and as I described in the previous article, RCA/NBC had located that facility in Burbank and was putting its efforts into getting good color pictures to the western United States.

The genius behind making these restorations possible, Ed Reitan passed away on January 5th this year in Los Angeles. As devoted as he was to the history of television, color television specifically and as respected as he was among those who made their livelihoods from television engineering, one would have thought he was a long time employee for the likes of RCA or one of the networks. But he never worked in the industry. He spent his entire working career with ITT-Gilfillan from his graduation from UCLA in 1963 until his retirement in 2005 working on things he couldn’t talk about. According to Reitan’s Linked-in page, his title was Manager of ATC Systems Engineering. ATC probably means Air Traffic Control since the company is involved in building air traffic control radar systems throughout the world.

At the same time he continued learning. Don Kent was surprised, as were others Reitan had contact with, to learn Reitan had received his doctorate from UCLA in computer engineering. But, Kent adds, “Ed was not one to talk about himself very much.”

Then for the last ten years since his retirement, he began devoting all his time to researching the history and the science behind color television. Kent remembers helping Reitan move back about half his collection of old televisions to Omaha, Nebraska, after Reitan’s father passed away in 1990. He was going back to live in his childhood home. He only owned two cars in his life – his father’s car and one his father gave him.

He continued to maintain the apartment in Los Angeles, near UCLA. Every year when he would be coming or going from his favorite vacation place, Escondido, CA, he would stop in to visit the remaining half of his old television and equipment collection. Kent describes Reitan as someone who “just liked old stuff,” in general but particularly if it had to do with television.

Ed Reitan in 1989. Courtesy Don Kent

Kent describes Reitan as someone who “would put himself back in the time period and wonder what did these people know – how did they think… how did they do what they did and then he would begin to reverse engineer.” To make his point, Kent uses the design of the circuit boards for the AVR-1 to extract the long extinct format and re-produce a usable color video signal.

As Kent says, Ed belonged in another time. But we are so lucky to have had him in our time so he could reach back to that earlier period and preserve some of it for all the rest of us and for generations yet to come.

My thanks go out to Don Kent and Dan Einstein for their time in preparation of this article. I also have to make special mention of Don Kent’s willingness to go out of his way to provide pictures and videos associated with not just this article but other historical videos about television he shared with me during our time together.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now