Two kilobucks, two pounds, and two megapixels: the Panasonic AG-HMC40 sits squarely in the gap between palm-sized consumer camcorders and pro-level handheld cameras with pro-level price tags. While it lacks some of the amenities of its larger cousins, it provides no-excuses, full-resolution HD imaging, 24 Megabit/sec AVCHD recording, and native 24fps frame rates for a street price around US$2000.

Overview

If you’ve been following Panasonic’s camcorders for a while, you may remember the DV-format DVX100 and its smaller brother, the DVC30. The 1/3″ DVX100 was the first DV camcorder to offer 24fps; the DVC30 sprang from the same design mindset but used 1/4″ CCDs and cost considerably less, while sporting a unique, removable T-handle.

In the same manner, the HMC40 can be thought of as the AG-HMC150’s younger brother: it’s half the cost and half the weight, and uses 1/4″ CMOS sensors in place of the 150’s 1/3″ CCDs. Like the DVC30, the HMC40 has a detachable T-handle, and it controls exposure the same way.

2004’s AG-DVC30 and 2009’s AG-HMC40 (not to scale).

Yet it offers AVCHD recording at up to 24 Mbit/sec (maximum, including audio; average video data rate is 21 Mbit/sec), interlaced and progressive imaging, and 24fps recorded as native 24p, without 3-2 pulldown. Both 720-line and 1080-line formats are supported, and the diminutive HMC40 steals a march on its bigger brother: the smaller camera uses 3.05 Mpixel sensors, with 2.51 million effective photosites in video mode: that’s more than the 2.07 million photosites needed to fully sample a 1920×1080 image. The HMC40 shoots a full-resolution, no-excuses-necessary HD image, and records it using the highest bitrate allowed in the AVCHD specification.

The HMC40 doesn’t have quite the button-per-function controllability of larger, more expensive cameras; its menu system is unnecessarily fiddly; like other small-sensor, high-resolution cameras it’s a bit challenged in low light. But it’s two megapixels of three-chip imaging in a two-pound, two thousand dollar package—you’ll pay twice to three times that amount before you’ll find anything that gives you a measurably better picture.

Design, Controls, and Handling

The AG-HMC40 is a compact, handle-less handheld camera; it fits in a box a foot long and five and half inches square, and weighs just over two pounds in shooting trim (in SI units, that’s 304mm x 136mm x 135mm, and 980g).

Left side, carrying handle not attached.

The body is finished in textured black paint, with smoother surfaces on the LCD housing and the handgrip. “Panasonic” and “HD” logos are chromed and “AVCCAM” (Panasonic’s moniker for professional AVCHD) is light blue, but aside from that the camera is marked and labeled in a businesslike white.

The HMC40 comes with a detachable T-handle that slots into an accessory shoe and has two captive screws to secure it in place. The T-handle is surprisingly seductive; it invites you to just pick up the camera and move it around even when there’s nothing to shoot. That the camera is a featherweight two pounds does nothing to dissuade you from this sort of aimless play.

Left side, with carrying handle attached.

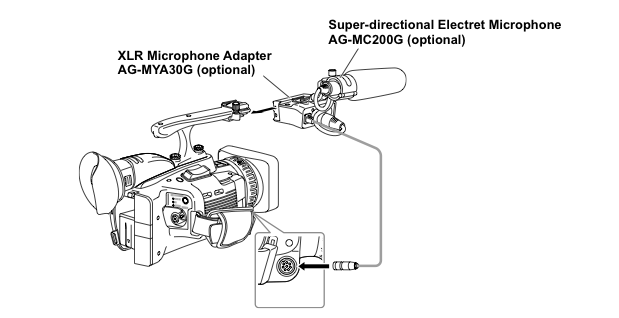

The handle has an accessory shoe on its front end, as well as attachment points for an optional XLR microphone adapter.

Optional XLR adapter (from page 82 of the HMC40 Ops Manual, © 2009 Panasonic).

A large lens shade bayonets into the front of the lens; it’s capped with a pop-off lens cap.

Front view: the HMC40 disappears behind its lens shade.

The lens shade removes with a simple twist; behind it there’s an anti-reflection baffle secured with a screwed-in locking collar. Both the lens shade and baffle come off to allow the fitting of an accessory wide-angle adapter, and they reveal a front element rather smaller than the diameter of the lens barrel might lead you to expect.

HMC40 with lens shade, anti-reflection baffle removed.

Removing the shade and baffle make it much easier to clean the lens, too.

User controls in front of the LCD.

The lens itself is surrounded by Panasonic’s trademark focus ring: a deeply ridged servo ring that’s easy to find by feel and turns easily, yet is smoothly damped. The ring spins freely, with no end-stops. It can also be set to control the camera’s iris or zoom.

Three buttons and a switch are arrayed aft of the focus ring, surrounded by slight ridges and distinguished by different textures. FOCUS ASSIST can be set to magnify the image or show a “focus bar” (discussed below). FOCUS switches the camera between auto and manual focus, and when held down it focuses the lens to infinity.

A two-position slide switch sets the focusing ring to control focus, or to control zoom or iris (the choice of which is made in the menus).

The WHITE BAL button cycles between 3200K and 5600K presets (so much faster than having to use the menus to select the color balance of a single preset, as many other camcorders require); continuous automatic white balance; holding the current AWB setting; and the A or B memories, the choice of which is made in a menu (more on this later). Holding the button down executes both white and black balance setting (or just AWB if the camera is recording, since ABB requires blanking the image).

Behind the buttons is a nicely knurled control wheel labeled IRIS. Pressing it inwards toggles between auto and manual exposure settings. When in auto, turning the wheel acts as an autoexposure compensation setting, biasing the image towards lighter or darker exposures. Opening the iris past its widest setting engages gain; the HMC40 doesn’t give you separate iris and gain controls—furthermore, IRIS isn’t always controlling the physical aperture; as we’ll see, it also engages a graded ND filter! Really, this control should be labeled EXPOSURE, since it uses three separate mechanisms to adjust image brightness.

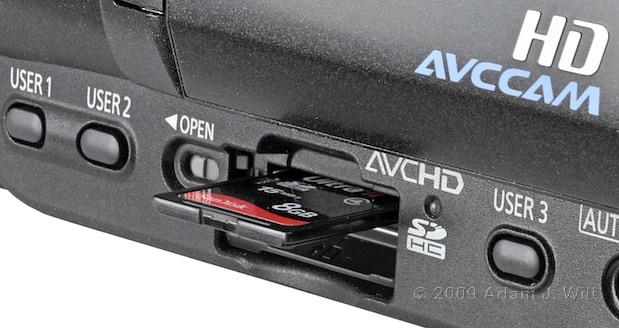

Two assignable USER buttons sit below the extended bulge of the lens barrel, ahead of the SD card slot and its OPEN slide switch.

SD cards slide in behind a flip-down door.

The card slot is protected by a flip-down door, which folds down into a little well below it. The well, and the gap around the door, seem designed to attract dust and grit; I would have preferred a flush-mount door that popped outwards. Once the door is opened, you can slide in an SD or SDHC card for recording video and stills onto. A bright yellow LED shows when the card is being accessed.

Controls and speaker behind the LCD.

Behind the card slot there’s another USER button, and a slide switch that select full-auto-everything mode or the MANUAL camera control mode.

Hidden behind the flip-out LCD are pushbuttons for color bars, a zebra display, and counter selection and reset buttons. There’s also a small speaker for playback audio monitoring. Aft of the LCD, and usable even with the LCD closed, are buttons to engage OIS (optical image stabilization) and to toggle the onscreen data displays or check current setting status.

The 2.7″ LCD itself appears to be borrowed from Panasonic’s line of HD palmcorders, like the HDC-TM300 (warning: PDF). It’s spring-loaded against the side of the camera but is easily flipped out, where it can be rotated through 270 degrees from facing forward to facing straight down.

The LCD has raised membrane switches on its lower bezel.

It has a row of raised membrane switches to call up the “quick menu” as well as the main menu; to start and stop recording; to zoom the lens at a fixed speed (or change the playback audio volume), and to delete a clip. These switches take a moderate amount of pressure, easily accommodated by pinching the LCD between thumb and forefinger. When the LCD is folded flat against the camera, though, it’s a different story.

With the LCD folded flush, the membrane switches are upside-down.

Not only are the buttons now upside down, the housing behind them is tapered slightly, so it isn’t flat against the side of the camera, and pushing the membrane switches firmly enough to activate them flexes the housing, making the LCD rock in place. It’s a bit unnerving, and not the least bit confidence-inspiring. It works, but it doesn’t feel good.

The screen itself is a touchscreen, used to interact with the menu systems and to set “touch focus” points. It looks perfectly horrible with the camera turned off—all covered with nasty, greasy fingerprints—but when the camera is powered up all that surface goop magically disappears and all you see is the image.

The LCD holds color quite accurately across a wide viewing angle, though finer tonal gradations suffer at oblique angles, with highlights merging and deep blacks washing out. This washout is minimal; compared to older Panasonic LCDs like the ones on my HVX200 and DVX100, it’s far superior. The LCD resolves only about 300 TVl/ph horizontally and 200 lines vertically, though it has a very fine, nearly invisible pixel pitch. The LCD shows 100% of the image with no nasty overscan or cropping.

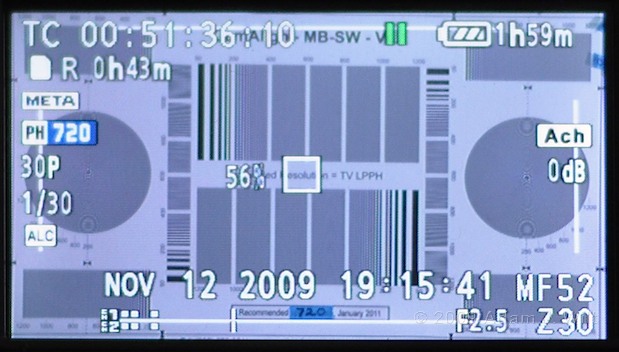

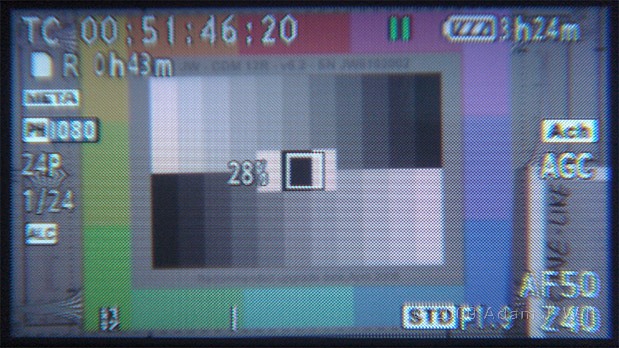

Data displays are up to Panasonic’s usual, comprehensive standards. Just about everything you would ever care to see can be enabled, so that you’re always on top of what the camera is doing.

Data displays on…

Focus is displayed as a number from 00 to 99, with an AF or MF indicator to auto or manual focus; zoom is also shown as a number from 00 to 99. Date and/or time can be supered in addition to timecode. The battery indicator is the usual Panasonic segmented fullness display, but it also shows an estimate of the time remaining on the battery. There is no histogram in video mode, but there is a zebra display as well as a percentage readout for the brightness of a central square (and a WFM, too; discussed later).

Of course, most of this gumpf can be removed with the push of a single button, leaving only transport status, timecode, and (if you’ve enabled them) safe-action markers and exposure readouts.

…and data displays (mostly) off.

Moving ’round to the back of the camera, there’s a rather small EVF with a rather large eyecup. The EVF can be flipped up to low-mode work, and it slides back in its track to make room for the T-handle (or any other accessory) to be slotted into the accessory shoe.

The back end of the T-handle has a round rubber bumper to protect the flipped-up EVF.

The EVF resolves no more than 200 TVl/ph horizontally and vertically, and its dot pattern is so prominent it really doesn’t serve as anything more than a “view finder” to ensure you’re pointed in the general direction of your subject: it’s not usable for focus, and it’s marginal for composition. It’s also hindered by its optics; whether I wore glasses or not, it was difficult to get my eye positioned such that the entire EVF panel was visible without cropping or vignetting.

The view through the HMC40’s EVF.

Nonetheless it allows for eye-level, head-braced viewing, something that EVF-less, fist-sized tinycams can’t offer. And if you’re using the HMC40’s waveform monitor on the LCD, the EVF lets you see your full image unobscured, so you can watch your shot while still keeping a weather eye on exposure and levels. As EVFs go, it may be unimpressive, but it definitely beats not having an EVF.

The battery slides into the camera below the EVF. The stock battery is a shortie, but the battery compartment will hold a high-capacity, full-height battery.

Rear view with stock battery, I/O ports covered.

Three separate flip-out covers on short tethers cover I/O ports. The top cover conceals a four-conductor miniplug for composite video and stereo audio and a D-shell analog component video output. The center cover hides the headphone jack. The lower cover protects two remote-control jacks: like the DVX, HVX, HPX170, and HMC150 cameras, the HMC40 offers comprehensive, repeatable remote control of aperture, zoom, focus, and start/stop. Using add-on controllers from Varizoom and Bebob you have as much remote control over the HMC40 as any Handycam-style camera allows.

I/O ports exposed, along with power switch and quick-start button.

The back of the handgrip has the usual start/stop trigger, surrounded by a rotary mode switch with a push-lock. Moving it to the momentary MODE position toggles the camera between shooting video, playback, and shooting stills.

The handgrip itself is nicely contoured, and ridged both for traction and to allow sweat to evaporate. Despite its aggressive look I found it very comfortable to use for long periods of time. The two holes above it appear to be ventilation slots.

AG-HMC40 right side view.

More I/O ports reside ahead of the handgrip: a full-sized HDMI output, a mini-USB connector, and a 1/8″ stereo mike input. Below those, with its own round cap, lies the multipin connector for the optional XLR audio adapter.

Carry-handle shoe and mikes on top; zoom rocker; front I/O ports.

A typical zoom rocker rests atop the handgrip; despite its small size it offers an impressive degree of zoom control. A small button behind the rocker lets you play back a bit of the previous recording, or triggers a photo in photo mode.

A standard accessory shoe sits on top of the camera; sliding the EVF an inch back on its track lets you slide in the removable T-handle, or another add-on like a mike holder or an LED light.

The camera has a built-in stereo mike beneath a grille set between the “sail” holding the EVF and accessory shoe, and the back of the focus ring. There’s a dark window in the front of the sail behind which a tally lamp and an IR sensor reside. There is no rear-mounted IR sensor, so the included remote only works in front of the camera.

The IR remote comes in handy for playback.

This is not much of a disadvantage as the remote is most useful during playback (though it has the usual start/stop and fixed-speed zoom functions for use while shooting). The comprehensive playback controls in the middle of the remote, along with the menu navigation controls, are much easier to use then the now-you-see-’em,-now-you-don’t touchscreen controls on the camera itself.

Next: Formats, Functions, and Features…

Formats, Functions, and Features

Formats

The HMC40 records AVCCAM—Panasonic’s name for professional AVCHD. It’s distinguished from “non-professional” ACVHD (at least in Panasonic’s lineup) by the availability of a 21 Megabit/sec video rate (24 Megabits including audio), 720p, and 24p-native recording modes, whereas Panny’s consumer lineup tops out at 17 Mbit/sec with no 720p capability.

AVCHD is a long-GOP variant of MPEG-4 using 8-bit sampling depth and 4:2:0 color subsampling. It is generally held to be about twice as efficient a codec as MPEG-2, so AVCHD files at 21 Mbit/sec should look better than HDV files at 25 Mbit/sec, with corresponding reductions in quality as the selected bitrate drops.

The HMC40 offers four bitrates, which in industry-standard practice it refers to by cryptic, nonstandard, and nonintuitive two-letter codes:

- PH mode – 21 Mbit/sec video, 384 kbit/sec audio

- HA mode – 17 Mbit/sec video, 256 kbit/sec audio

- HG mode – 13 Mbit/sec video, 256 kbit/sec audio

- HE mode – 6 Mbit/sec video, 256 kbit/sec audio

The PH, HA, and HG modes record 1080-line video at a full 1920×1080; HE uses a 1440×1080 sampling raster. Dolby digital compression is used for the audio, which is sampled at 48kHz and 16 bits per channel.

The camera records the following formats:

- 1080/60i

- 1080/30p (2:2 pulldown on 60i)

- 1080/24p (native recording)

- 720/60p

- 720/30p (each frame recorded twice atop 60p)

- 720/24p (native)

All formats are available in PH mode; the lower-bitrate modes only offer 1080/60i.

Even though 1080/30p is recorded as a 60i stream, the images are captured and encoded as progressive (as are 1080/24p and all the 720p formats), so they benefit from progressive 4:2:0 encoding, not the fundamentally broken 4:2:0 interlaced encoding.

4:2:0 interlace vs. progressive encoding on the HMC40.

True progressive 4:2:0 encoding is a major advantage of Panasonic’s AVCCAM format; by comparison, consumer cameras like the Canon HF11 may offer 21 Mbit/sec recording and 24p capture, but use interlaced encoding, so The Dreaded Chroma Sawtooth Jaggies are always an issue.

Menus and Functions

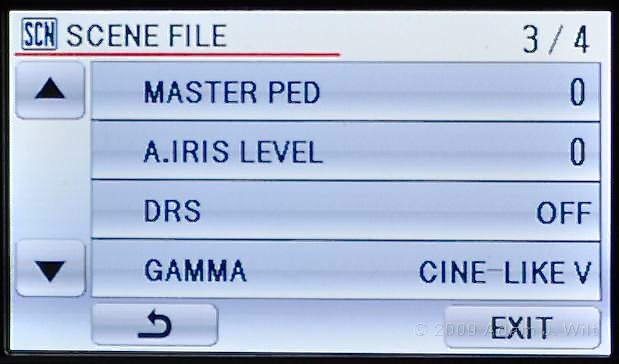

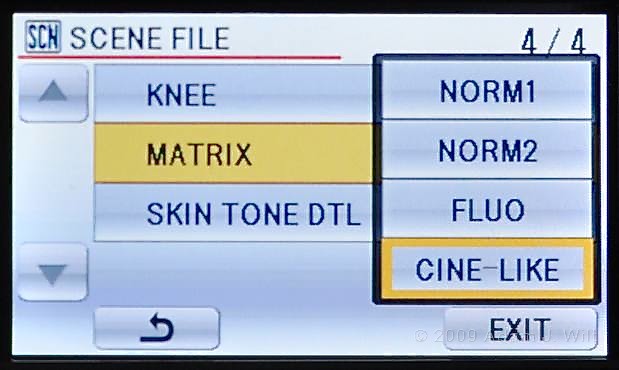

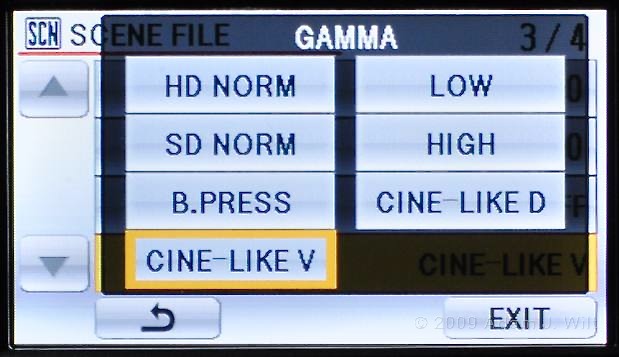

The HMC40’s menu settings will be largely familiar to users of other Panasonic prosumer / affordable pro cameras, from the DVX100 through the HPX300. There are four color matrices; seven gamma settings; the usual controls over color saturation, phase, and color temperature, detail level and H/V detail balance, knee, and so on. Rather than describe them all here, I refer you to the 19 MB PDF of the AG-HMC40 Operations Manual; menus are discussed on pages 95-111.

Unfortunately the menu consistency of the HMC40’s predecessors is lacking: control of the HMC40 is spread across three entirely different menu systems.

Warning: what follows is a bit of a curmudgeonly rant. In a previous life I was a user interface / control panel designer for broadcast graphics products, so I’m probably more sensitive to interface-design issues than most people.

The Setup Menu contains most of the stuff you’d use to set up the look of the images; this includes items that reside in the Scene File menus on the P2 Panasonics (the HMC40 doesn’t offer six scene files with their own selection dial, just two scene files loaded though the setup menu). This menu is brought up by pressing the MENU membrane switch on the LCD, and it displays a full-screen, graded silver UI:

Setup Menu: scene file items.

You navigate the menu using the LCD touchscreen; this explains the screen-filling buttons which obscure the image entirely.

If you select an item with only a few options, you get a submenu like this:

Setup Menu: four-item submenu.

If there are more than a few choices, you get a popup instead:

Setup Menu: seven-item submenu.

Choosing any of these subitems sets the appropriate parameter, but you can’t see the effect immediately unless you have a separate monitor hooked up to the camera, since the menus fill the LCD and EVF. Yes, you can clear the menus to see the image, but it makes making A/B comparisons between parameters difficult without using a separate monitor.

Fortunately, items with numerical parameters let you see the image as you’re dialing in the value:

Setup Menu: variable parameter setting.

Why the variable-parameter display uses a solid blue background instead of the menu’s graded silver remains a mystery.

If you want to choose your recording format, turn on pre-record, set LCD brightness, or change microphone or headphone levels, you use the Quick Menu, invoked with the Q. MENU membrane switch.

Quick menu: format selection.

Note the black borders (neither blue nor silver); the rectangular buttons arrayed on the camera’s live image; the smaller font and the use of icons; the EXIT button placed on the left (it’s on the right in the Setup Menu).

The format selection screen shows all the combinations of allowable frame sizes, frame rates, and recording qualities, but they’re all jumbled together instead of being arrayed by these parameters. You have to squint at the screen and read through the text on the icons to make sure you’re really getting what you want; the third column commingles dissimilar recording qualities, frame sizes, and frame rates—impressive, considering it only has two items!

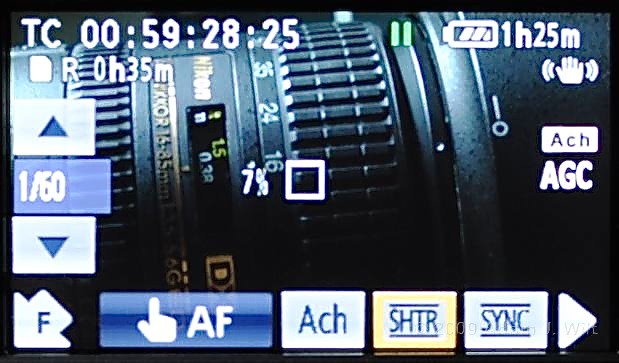

If you want to change certain shooting parameters, like shutter speed, synchro-scan, whether the A or B white-balance memory is active, or if you want to engage touch-focus mode, you use the Function Navi menu: you tap the touchscreen, and a small arrow appears in the lower left corner. Tap it to display a menu across the bottom of the screen, which you can then select items from and twiddle their values:

Function Navi menu: choosing a shutter speed.

When you’re done, you have to tap your selected item again to close the value-twiddler. You can then tap the diagonal arrow again to hide the menu, or leave it alone for a few seconds, after which it’ll disappear by itself.

Once I select my desired shutter speed, I shouldn’t have to tap SHTR to proceed; I should be able to tap the diagonal arrow to dismiss the menu directly, or just wait for it to vanish on its own (perhaps after a longer-than-normal delay). And if I tap the screen to begin with, why do I have to tap the little arrow for the menu to display? It’s not like it covers up the entire screen. Changing the shutter speed by one increment takes five onscreen taps; it shouldn’t take more than three.

A small matter, perhaps, but it certainly slows operations down in the heat of battle. The menu design is the most frustrating thing about this otherwise user-friendly camera; it’s just not up to Panasonic’s usual high standards.

For all my complaining, though, the menus do give you reasonably quick access to those things not available on physical switches and dials.

Rant over. We now return you to your regularly-scheduled program, already in progress…

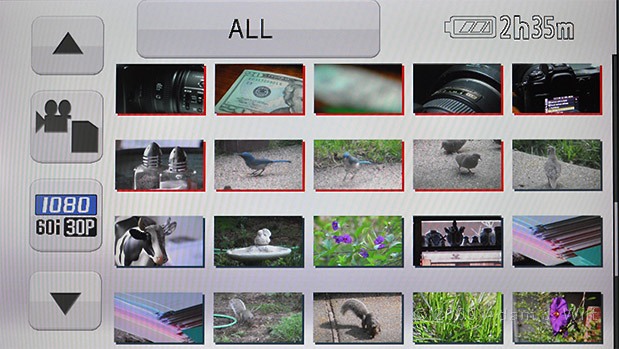

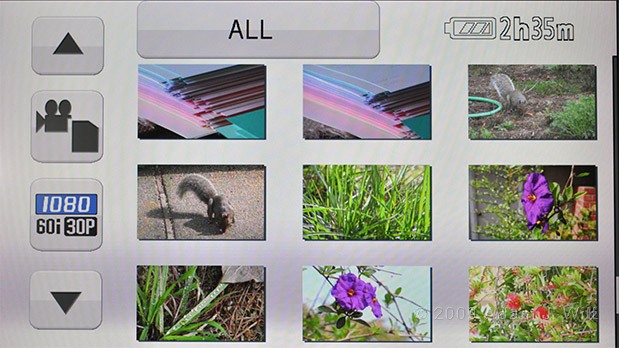

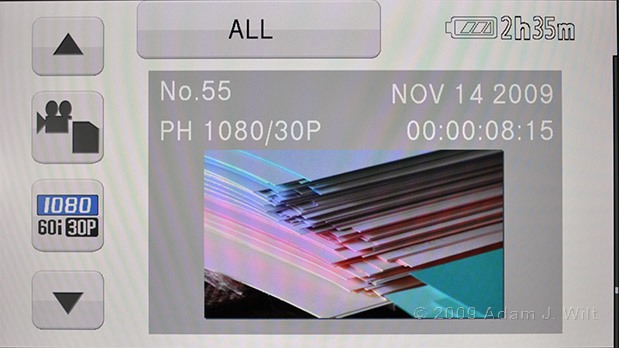

The camera’s playback mode offers a thumbnail view for quick navigation, with varying detail levels. Clips unplayable in the current format are outlined in red, but there’s a current-format icon in the margin so you can quickly change modes as needed. You use the zoom rocker on the camera to “zoom out” to see more thumbnails, or “zoom in” to see a larger thumbnail or clip details—it’s a fast and intuitive way to work.

Playback: zoomed out on a clip list.

Playback: normal display of a clip list.

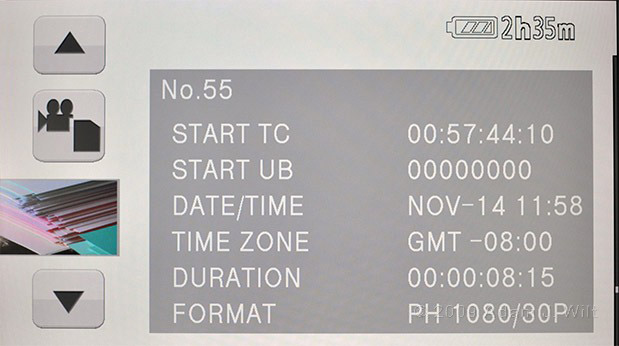

Playback: details of a single clip.

Playback: additional clip metadata.

Once you select a clip for playback, you can use the touchscreen to play or pause, shuttle forwards or backwards, or single-frame forwards or backwards (in reverse, clips skip by half-second intervals due to their long-GOP nature). You can also bring up a clip timeline, letting you touch and drag the playhead to a desired point.

If you keep your finders off the screen for more than three seconds, the controls vanish, reappearing if you touch the screen again. Especially when looking at clips frame-by-frame, I preferred to use the IR remote, since its physical buttons didn’t disappear on me and were always findable by touch. The remote also has “skip” buttons letting you jump to the next or previous clip; the touchscreen lacks these controls.

Features

The HMC40 inherits features from both the consumer and pro sides of the business, giving it a unique mix of capabilities. How often do you find a camera that can track faces automatically, and show you a waveform monitor at the same time? (Answer: Not too darned often!)

A Waveform monitor is available the push of a button:

The HMC40 offers a WFM on the flip-out LCD.

The WFM appears on the flip-out LCD only, so it’s perfectly possible to operate the HMC40 with one eye to the EVF for composition while monitoring exposure on the WFM with the other eye. I assigned the WFM to one of the USER buttons so it was immediately available whenever I wanted it.

This WFM, also seen on the AG-HPX170 and similar Panasonic cameras, is hugely beneficial whenever accurate image control is required, whether it’s seeing what exposure levels are on a location, adjusting lights on a set, or evenly lighting a greenscreen.

The WFM works in video recording only; the still camera mode (which I’m pretty much ignoring in this review) offers a histogram in its place, letting you check levels of captured images.

Zebra can be displayed starting at any level from 50% to 105% in 5% intervals.

Center-marker exposure readout gives you the brightness percentage of a small boxed region of the screen; think of it as a spot meter.

Focus Assist lets you magnify the image or superimpose a “focus goodness” bar, or both.

Focus assist: zoomed in, with focus bar and “peak hold” marker.

The zoomed-in picture displays on the LCD and EVF with a blue frame so you know you’re in magnify mode. The focus bar grows to the right as focus is improved, and a “peak hold” marker shows you the longest focus bar you’ve managed to achieve in the last few seconds, making focus finding more certain. With both magnify and the bar enabled, I found that Focus Assist worked quite well in getting me to my desired focus point with a minimum of flailing about.

Touch Auto Focus is enabled from the Function Navi menu; it frames most of the screen (basically the area above the Function Navi menu area) in red, within which you can touch the image to set a focus point. In manual mode, it’ll focus in on that point and stay; in auto mode it’ll track focus in that area of the screen. Tap outside the red zone to display the Function Navi menu, then tap the touch AF icon to cancel the mode.

Face Detect focusing will look for faces in the scene, detecting up to fifteen faces and focusing on the largest, most centrally located one.

Pre-Rec constantly captures video in a buffer, so that when you press the start trigger, you get a recording of your clip from three seconds before you hit the trigger up until you stop the recording.

Interval Recording (time-lapse) grabs single frames at intervals of 1, 10, 30, 60, or 120 seconds. The camera is automatically set to 1080/24p mode for interval recording.

You can set the iris dial to work in roll-up-for-brighter or roll-down-for-brighter mode.

You can set the lens ring mode to toggle between focus and zoom, or between focus and iris (which may seem silly since you have a dedicated iris wheel, but the large ring affords finer control than the small dial).

Three user buttons can be assigned any of the following functions:

- Push AF, to autofocus when the button is held down.

- Backlight compensation.

- Spotlight compensation.

- Fade to/from black.

- Fade to/from white.

- ATW (auto-tracking white balance) on/off.

- ATW lock.

- High gain, to allow a one-button gain boost up to 34dB.

- Digital Zoom, toggling through setting of 1x, 2x, 5x, and 10x.

- EVF DTL, to add a sharpening signal to the EVF and LCD displays.

- Shot Mark, to tag a shot during recording or playback.

- Last Clip Delete.

- WFM display.

- No function at all, in case you’re overwhelmed by choices.

Slow shutters down to 1/2 second can be used, capturing more light and giving a strobed, low-frame-rate motion rendering.

Synchro Scan lets you finely tweak shutter times to eliminate flicker from CRTs and other non-continuous light sources.

Microphone levels can be set manually or automatically. Note that level setting occurs through the menus; there’s no physical knob on the camera you can twist to change audio gain, and that you tweak both left and right channels simultaneously.

The optional XLR adapter ($280 street price) affords more control on a per-channel basis, but I didn’t have one to test. Panasonic tells me it has two independent volume controls as well as two-position attenuator switches. Each input is individually selectable for line or mike levels and +48v phantom power; input 2 can be set to feed channel 2 alone, or channels 1 and 2 together.

The HMC40 lets you burn in the current time and/or date across the bottom of the image, making it a suitable camera for recording legal depositions and the like.

The camera works as a still camera, too. I just didn’t explore that capability for lack of time. Go beat up on the folks over at ProPhotoCoalition for a photo-oriented review, grin. I will say that it offers stills from 4224×2376 down to 640×480, an exposure histogram during playback, and the ability to create slideshows complete with built-in music. The mind boggles.

Next: Performance, Samples, and Conclusions…

Performance

It’s a two thousand dollar camera with quarter-inch sensors, fercryinoutloud, so you would not expect much. You would be wrong: while the HMC40 won’t obsolete your Varicams and 3700s, it does surprisingly well.

Optics

The Leica Dicomar 12x Zoom runs from 4-48mm, or 40.8-490mm in 35mm still camera terms. It takes 43mm filters. Using the zoom rocker, a fast zoom took three seconds (which isn’t particularly fast), while a slow zoom took two and half minutes (plenty slow enough to execute gradual pushes and pulls. The lever affords fine-grained, positive control, making it easy to ease smoothly into and out of zooms.

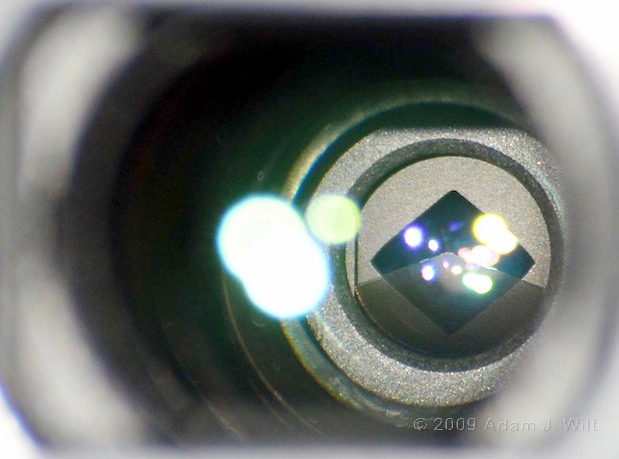

The iris uses a four-sided, diamond-shaped aperture from wide open to about f/2.8, then a graded ND filter slides up in front of it for effective apertures (as far as exposure is concerned) between f/2.8 and about “f/6.8”. Below “f/6.8”, the physical aperture appears to shrink down again to “f/11”, then it caps.

Looking into the lens: four-sided iris, graded ND rising up over the aperture.

The use of the ND filter for the midrange settings (a feature also employed in the earlier DVC30) allows a larger physical aperture to be used for most exposures, delaying the onset of diffraction-based softening. However, it reduces the ability to get deep-focus images (imagine: complaining about shallow depth-of-field on a quarter-inch sensor!), and it may help explain the camera’s rather unusual flare performance as discussed below. It does mean that the optical sweet spot of the lens is f/2.8; going smaller doesn’t change any of the basic optical properties until you get past “f/6.8”, at which point you now have an extra bit of glass (the graded ND filter) in the path and diffraction starts to be a concern.

Zooming in causes a gradual and continuous decrease in maximum aperture from f1.8 to f2.8. Exposure across the frame is absolutely flat below Z85 (the camera reports zoom setting as Z00-Z99, and focus as F00-F99), and only drops about half a stop in the corners by Z99—and it’s a very gentle, soft-edged vignette that doesn’t call any attention to itself. Zoomed in past Z65, OIS (optical image stabilization) causes some exposure variations in the corners as the OIS steers the image around to remove shake; at worst this is a one-stop variation from darkest (image steered away from a corner) to brightest (image steered towards that corner). Because an ND filter is used for “apertures” between f/2.8 and f/6.8, stopping down the lens doesn’t improve these vignettes until you’re past f/6.8, so it’s a good thing that the vignetting on this lens is so mild to begin with.

Distortion throughout the zoom range is so low as to be virtually nonexistent. There is just a tiny bit of pincushioning towards the corners of the image, but I mention this only to prove that I went looking for it; it’s nothing that you’ll ever see in any practical shooting situation.

The HMC40’s near focus behaves like no other camera I’ve used. Most cameras focus most closely at full wide angle, with the minimum object distance increasing as they zoom in. The HMC40 focuses to just inside its lens hood through the first 50% of its zoom range, with the M.O.D. increasing to F49 (about three feet) at Z80 through Z86, then decreasing to F41 (about 21 inches) at Z99. Until I got used to this, I surprised myself several times by zooming into something nearby, focusing, then slowing pulling out, only to have my subject fuzz irretrievably out of focus.

The lens is more than adequate as far as basic resolving power is concerned. None of my mid-zoom to telephoto shots were anything less than pin-sharp. However, it sometimes lacked a bit of crispness in wide shots; I think the lens may be slightly softer at full wide angle that when it’s zoomed in a bit. As you’ll see below, resolution charts look pretty darn good, but they were shot with the lens zoomed in a bit; I didn’t think to check the lens’s chart performance at the extremes until after I had returned the camera.

There is no obvious lateral chromatic aberration—Panasonic may be correcting for it in-camera. There was a bit of vertical green-magenta separation on out-of-focus areas (a prism effect common in three-chip cameras), a bit of purple fringing on heavily overexposed areas, and occasional, varying amounts and colors of flare and out-of-focus edging. The latter effects I attribute to the varying position of the slide-up internal ND filter; it has a glass edge that is often in the path of the light, and I suspect there may be diffraction, refraction, and/or reflection off that edge that causes the odd yellow, magenta, green, red, or cyan flare to appear at times, always subtly and never predictably. It was never so intrusive as to be a issue; I was looking for problems and thus saw flare, but if I hadn’t been searching for something to complain about, it wouldn’t have called any attention to itself.

Purple fringing on the bright sky and flare on the edges of some sunlit leaves, barely visible in this shrunk-down image.

What’s more immediately obvious is the bokeh: the appearance of out-of-focus areas. The HMC40 uses a diamond-shaped aperture, and the bokeh echoes that shape:

Throwing the image out of focus reveals a diamond-shaped bokeh.

Sometimes it’s more visible…

Background specular highlights, and some cyan highlight flare.

…sometimes it’s less visible…

More out-of-focus background bokeh.

…and sometimes it just isn’t something that calls any attention to itself:

Beauty shot: small sensors don’t preclude shallow depth of field.

Droplets left by a brief rainstorm.

The HMC40’s macro range allows easy close-ups.

Resolution

The HMC40 uses 1/4.1″ CMOS sensors with 2.51 million effective photosites when shooting video, out of 3.05 million total. As a 1920×1080 image contains 2.07 million pixels, the 2.51 number implies a slight oversampling in the HMC40 (interestingly, Panasonic’s consumer cameras like the HDC-TM300 have a chip of the same size and photosite count, yet they are specified to use 2.07 million effective pixels when shooting video. Go figure…).

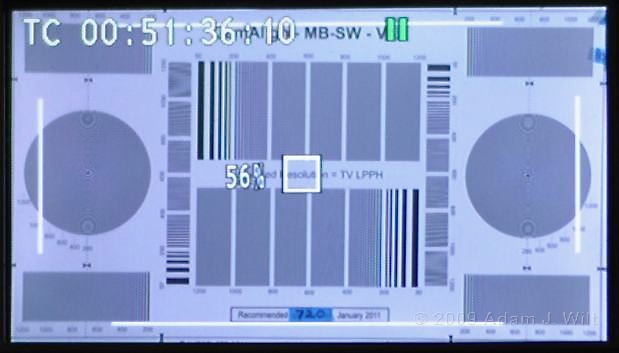

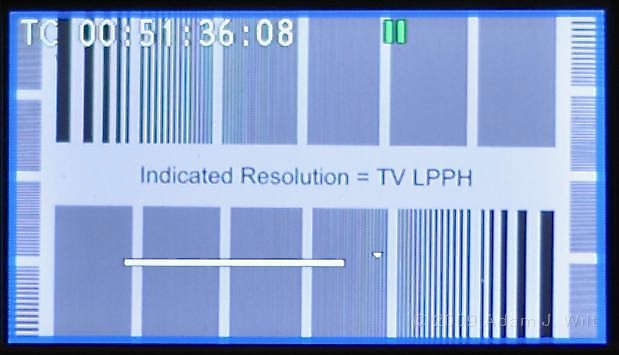

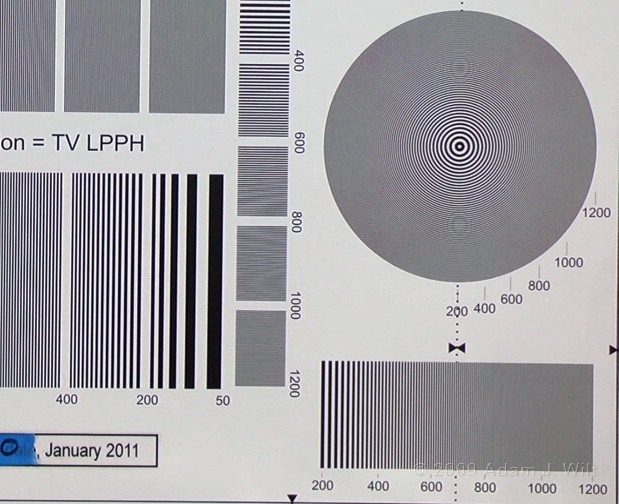

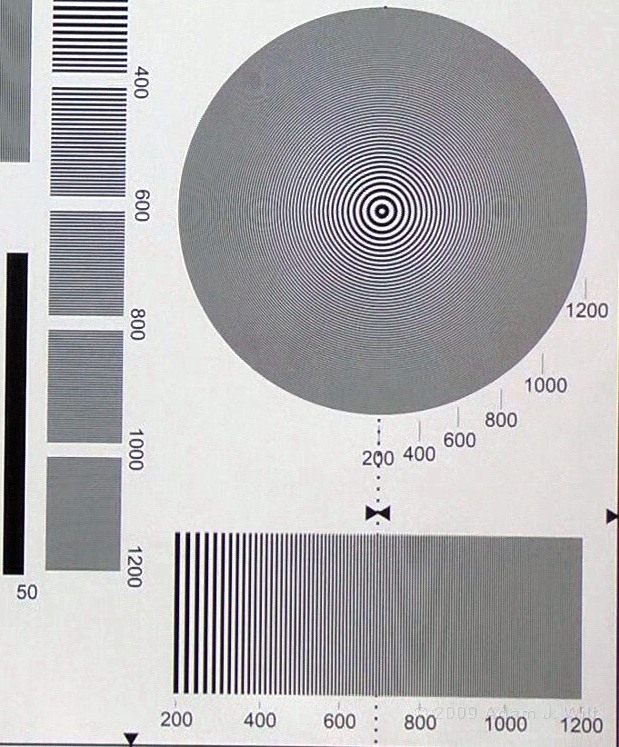

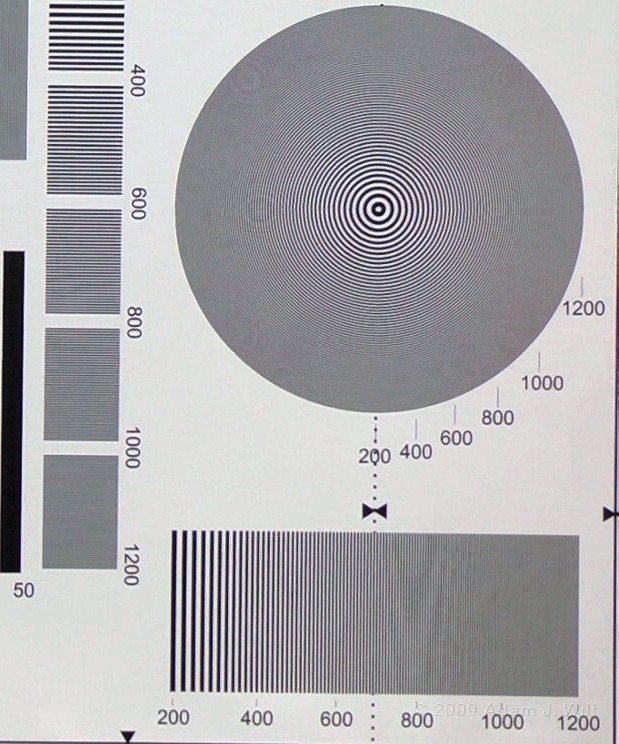

In short, this little camera should be able to shoot a full-resolution, true HD image. It does not disappoint, as these pixel-for-pixel DSC Labs multiburst chart images show:

720/24p recording in 24 Mbit/sec AVCHD, pixel-for-pixel.

1080/60i recording in 24 Mbit/sec AVCHD, pixel-for-pixel.

1080/24p recording in 24 Mbit/sec AVCHD, pixel-for-pixel.

By the standards of cameras costing ten times as much or more, these pix might be faulted for slightly high aliasing, but in the real world the HMC40 is a superbly sharp and clean performer. The camera smoothly resolved real-world details of a single pixel’s width, and let those details move across the face of the sensor without a trace of jagginess, “screen-door” effect, or twinkling of any sort—the HMC40 is a no-excuses, full-resolution HD camcorder.

Compare these charts to one shot by the Canon HF11 and you’ll see that three full-res chips make a difference—the Canon makes a very respectable image for its price, but the HMC40 cleanly outclasses it.

Sensitivity and Noise

All else being equal, small sensors will suffer compared to large sensors when it comes to sensitivity and/or noise. This camera is hungry for light; I rated the HMC40 at an effective exposure index (EI, a.k.a. ISO) of 80. It may be that Panasonic has biased the EI of the camera low to improve noise performance; the camera has no negative gain settings, which tends to support the theory that at EI80 / 0dB the sensors are already “exposed to the right” as far as possible: there’s no headroom in the highlights to allow for negative gains. Indeed, boosting gain to +6dB (an effective EI of 160) results in a picture that looks very nearly as good as a picture shot at 0dB, so don’t let the low EI rating turn you off.

Image noise is surprisingly low; it’s only a bit higher than noise on 1/3″ CMOS cams with lower-resolution sensors. What noise there is tends to appear as soft-edged “grain” and mild chroma noise, and the HMC40 appears to use fairly aggressive (and effective) noise reduction, since noise doesn’t build nearly as much with higher gain as one might expect. There’s some resolution loss with gain boost, starting to become noticeable on the charts at +12dB, but the image at +18dB still looks about as crisp as the image at 0dB—and its noise is much less distracting than the noise on many other small-format camcorders at comparable gain settings. Only at +24dB and above does the image start to soften up, with resolution dropping below 800 lines, and it’s still quite usable for many purposes.

The HMC40 fares much better in low light than many other small cameras I’ve tested; some might say that the noise reduction is too aggressive for their tastes, but I found that it made for pleasing images at higher gains than I would have expected. Documentary shooters shouldn’t discount the HMC40 despite its low EI rating.

Tonal Scale and Color

The HMC40 behaves like most small Panasonics in terms of its tonal scale handling; it seems to have a bit more than eight stops of usable dynamic range. If I were to fault it on anything, I had the impression that it tends to clip highlights a bit sooner and a bit more harshly than some of its 1/3″ siblings. I attribute this to its low EI rating: if the sensors and processing are biased towards higher exposure / lower noise, they have less highlight headroom as a result. Mind you, this is a subtle thing, and might be as much a construct of my overactive imagination as it is an artifact of the camera itself.

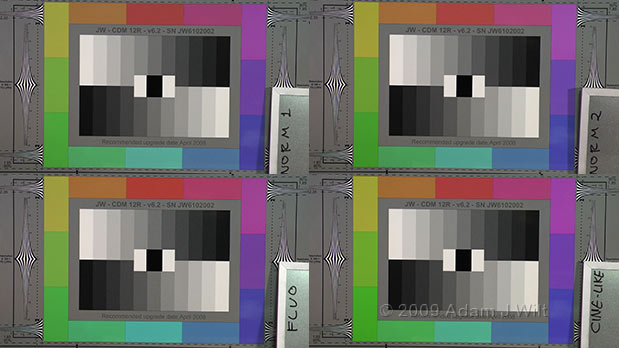

Like many other Panasonics, the HMC40 has seven gamma presets. Five are traditional “video gammas”:

- HD Norm – standard high-def gamma, slightly darker midtones than SD Norm.

- SD Norm – same standard-def gamma as in the DVX100.

- High – a higher-key gamma that brightens midtones.

- Low – a low-key gamma that slightly darkens midtones.

- B.Press – “black press” low-key gamma with slightly crushed shadows.

These curves let you choose between three fixed knee points: Low, where the knee kicks in at 80% brightness; Medium, with the knee point at 90%; and High, with knee starting at 100%. An Auto setting lets the camera vary the knee point automatically as it thinks is appropriate to the scene.

You also get Panny’s celebrated cine gammas:

- Cine-like D: “dynamic”; a fairly flat gamma curve with moderate contrast.

- Cine-like V: “video”, a somewhat contrastier curve with excellent highlight rolloff.

These gammas use a fixed, high knee, which rolls off highlights instead of letting them crash suddenly into nasty clipping. Cine-like D is recommended for clips headed for manipulation in post; Cine-like V is more immediately usable as-is, with a bit more contrast. I prefer to shoot my Panasonics (I own a DVX100 and an HVX200) in Cine-like V almost all the time, as Cine-like V handles overexposed flesh tones very naturally, with less of a jaundiced yellow highlight than standard gammas do (not just on Panasonics, on most cameras), and a smoother transition into clipping than a standard knee offers.

Having said that, the selection of gammas lets you vary the look of the image considerably, if subtly, so that you can set up the look that’s most appropriate to your situation. Just remember to have a separate monitor handy, as the HMC40’s full-screen setup menu makes immediate A/B comparison of gamma changes impossible on the camera’s LCD.

The four color matrices in the HMC40.

The HMC40 also offers four familiar color matrices. Combined with Panasonic’s usual saturation, phase, and balance (warm/cold) controls, you have a lot of control over the look of the camera’s colors.

The HMC40 has the same basic colorimetry as other Panasonics: colors are very natural and pleasing, with no particular bias. Reds in the image are as truly red as they were in the scene; greens and earth tones look like real life.

The HMC40 has Panasonic’s natural colorimetry.

The colors in this image precisely match those of the real maple.

I tend to leave the matrix on Norm1 and maybe turn saturation down a bit, but aside from that I leave Panasonic colors alone, because They Just Work.

Recording Quality

The HMC40 record AVCHD, a variant of h.264, a.k.a. AVC, a.k.a MPEG 4 Part 10. The camera’s PH recording mode, at 21 Mbit/sec, should theoretically be almost twice as good as MPEG-2 at the same bitrate, so it should outperform 25 Mbit/sec HDV.

In practice, PH mode does indeed outperform HDV, holding more detail with fewer artifacts even in the presence of high static detail (image complexity) and high dynamic detail (lots of fast picture changes). As one might expect, the 24p native modes show fewer artifacts than the 60i or 60p modes; the camera uses the same bit rate to compress fewer frames, so the per-frame compression ratio drops. Have a look at the multiburst charts above, and compare the mosquito noise (compression artifacts) around the text in the 1080/60i chart to that in the 1080/24p chart.

The other recording modes the camera offers trade off bit rate for longer recording times; the quality falls off accordingly.

I have only one quibble with Panasonic’s AVCHD implementation, and it’s a small one: sometimes the first few frames in a clip can be a bit coarse and blocky. Some fine detail may be missing in the first frame, but builds in over the course of the first half-second: the duration of a GOP, or Group Of Pictures compressed as a standalone unit. Subsequent GOPs are fine.

A wide shot, and CUs of the 1st and 14th frames as fine details fill in.

Many (most?) advanced codecs use information from previous frames to determine bit allocation on the current frame, as there’s usually a high correlation of image information from frame to frame. Even at the start of a GOP, this information helps the codec efficiently allocate bits on the fly. If I had to guess, the HMC40 isn’t “precharging” its codec with this predictive information while recording is stopped; it’s only waking the codec up when you mash the record button, so the poor thing has to start from scratch on the first frame of the clip, and play catch-up.

It’s a subtle thing, and it’s only visible occasionally, but it’s not something I’ve seen in AVCHD cameras from a couple of other manufacturers (I also shot the scene above with a Sony AVCHD camcorder, and saw no such difference between the first and subsequent frames). If you typically use the first quarter-second or half-second of your raw clips in your finished show, it’s something to be aware of, but it’s not something that should frighten you off.

Etc.

It’s a CMOS camera, so there’s no vertical smear on overexposed highlights. It uses a rolling shutter, so there’s some image shear on fast pans and some “jellocam” distortion during shakycam-style conniption fits, but it’s no worse than on any of the CMOS Sonys I’ve been working with in the past couple of years; it’s not an issue in most practical situations.

The stock battery is an inch-and-a-half cube rated at 2500 MAh; it runs the camera for about three hours.

The iris readout is shown in 1/6 stop increments, which affords a very fine degree of control.

The camera’s Dynamic Range Stretch (DRS) function works like the “Highlights and Shadows” functions in various image editors: it selectively boosts shadows and brings down highlights in localized areas, giving you some of the benefits of high-dynamic-range imaging. Used judiciously, DRS lets you see farther into highlights and deeper into shadows; used to excess or on the wrong scenes, and you may see some “halo” effects:

Dynamic Range Stretch on high, when the operator wasn’t paying attention.

DRS has three preset levels (low, medium, high) as well as an automatic setting; it’s a very useful thing to have when you need it (see the sample image here), but it’s not something to leave on all the time—with powerful tools come powerful responsibilities, responsibilities I obviously shirked during the shooting of this particular HMC40 clip.

The diamond-shaped iris sometimes throws off X-shaped starbursts on specular highlights, especially at smaller apertures.

I only used the built-in mikes during my brief time with the camera. They proved to be sensitive, reasonably flat in response, and less subject to camera-handling noise than I would have expected. For serious use, I’d suggest adding a separate miniplug mike, or the optional XLR adapter with phantom power.

As audio levels are controlled though the Quick Menu and are not available on a dedicated knob, you’ll want to pre-set levels carefully. The HMC40 is not a camera that lends itself to on-the-fly audio leveling. Of course, if you’re using the XLR adapter or a separate mixer to control audio, it won’t be an issue.

Conclusions

As far as I can tell, this is the best-performing HD camcorder you can get for the price. Mind you, there’s not much competition in the class of cameras between $1000 fist-sized tinycams and four-pound-plus, $4000+ handhelds, but even so, in many ways the $2000 HMC40 outperforms cameras costing twice as much or more.

It’s a true, full-resolution HD camcorder that yields smooth, highly-detailed 720p, 1080i, and 1080p images without any nasty aliasing artifacts. It has Panasonic’s pleasing colorimetry, and the same set of gammas, matrices, and image tweaks as the DVX/HVX camcorders. It’s smaller and lighter than anything else that affords a similar degree of control over the image, and its removable T-handle lets it pack down even smaller, for times where a compact and unintimidating form factor is called for. It records high-quality images on small, inexpensive SDHC cards available at almost any photo or electronics store. Oh, did I mention it’s only $2000?

On the flip side, the camera’s diminutive but high-resolution sensors result in a lower exposure index and slightly higher noise than larger, more expensive cameras have. It lacks separate aperture / gain / ND controls, rolling them all into a single “iris” setting. Some frequently-needed settings, like shutter speed and audio levels, lack dedicated controls and are only accessible through the touchscreen menu system. XLR audio inputs require an optional adapter (but at least the camera is set up to accept such an adapter).

The diamond-shaped aperture and the sliding ND filter, with their attendant bokeh, flare, and starburst looks, give the camera its own distinctive aesthetic. Whether you consider this a benefit or a detriment depends on your own artistic judgement; I quite like it, myself. Fortunately these aspects of the HMC40’s imaging are subtle enough that they don’t preclude using the camera for routine, just-the-facts-ma’am shooting—but they’re there when you want to exploit them for a bit of added, impressionistic impact.

Pros

- True, no-compromise 1080p imaging.

- 1080p, 1080i, and 720p recording at AVCHD’s highest bit rate.

- 24p-native modes for the highest quality 24p possible.

- Handy, removable T-handle.

- Full manual focusing with helpful focus assist modes.

- Multiple autofocus and touch-to-focus modes in addition to manual focus.

- Waveform monitor, zebra, and center-marker exposure readouts.

- Full manual exposure control.

- Panasonic’s natural colorimetry; flexible gamma selection.

- Cine-like V gamma handles skintone highlights as well as anything I’ve seen.

- DVX/HVX-style image tweaks: comprehensive without being overwhelming.

- Solid-state recording on readily available, inexpensive SD and SDHC cards.

- Pre-record and interval recording modes.

- Low-distortion, sharp, 12x zoom with excellent low-speed control.

- Slow shutters to 1/2 second; synchro-scan for shooting CRTs and other flickering things.

- Allows full remote control of start/stop, zoom, iris, and focus.

- Very good noise reduction when gain is boosted.

- Cameras shipped through March 2010 come with a copy of Edius Neo 2 NLE software in the box.

- Also usable as a still camera.

- It’s only $2000! It weighs only two pounds!

Cons

- Lower sensitivity than larger cameras offer.

- Somewhat higher image noise at low gain than larger cameras have.

- Aperture, gain, and ND are all on a single “iris” control.

- Limited real-time audio controls without the optional XLR adapter.

- Annoyingly inconsistent and tap-intensive menu systems.

- Maximum zoom speed is a bit slow (three seconds end-to-end).

Cautions

- Purple fringing on overexposed highlights.

- Highlight clipping can seem a bit harsh.

- Diamond-shaped bokeh, X-shaped aperture flare, and occasional multicolored highlight flare add an impressionistic look.

- Initial frames of some clips aren’t as well-encoded as the rest of the clip.

- DRS, used incautiously, may result in contrast haloes.

- As with other AVCHD camcorders, there are no variable frame rates.

- Serious audio requires the optional XLR adapter.

- No SD card in the box; you’ll have to buy one before you can record anything.

Would I buy one? If I were cash-constrained, nothing else shoots a full-res 1080/24p image nearly as well for anything close to its price. If I were having to travel light, the HMC40 packs more pixel punch and more usable manual control than any current fist-sized tinycam does.

As it is, I have access to fancier (and more expensive) HD cameras at work, but I’m still looking for something small and light—yet with as few imaging compromises as possible—to keep around for “sketchbook” uses and for casual experimentation. The Canon Vixias are attractive, but lack 24p-native recording and usable manual focus; the Panasonic TM300 has manual focus but lacks both progressive capability and 21 Mbit/sec recording. If nobody comes up with a tinycam combining full-bitrate AVCHD recording, true progressive encoding, and decent manual controls, there may well be an HMC40 in my future.

More info:

AG-HMC40 on panasonic.com.

AG-HMC40 Operations manual (19 MB PDF)

Barry Braverman’s review at Millimeter / DigitalContentProducer.com

16 CFR Part 255 Disclosure

I asked Panasonic’s PR folks to send me an HMC40 for review, and they did so. I returned the camera to them about two weeks later at my own expense. All hardware, software, and documentation sent to me for the review has been returned to Panasonic; I downloaded an electronic copy of the Operator’s Manual from Panasonic’s website, just as anyone else can.

I purchased my own 8GB SDHC card at Best Buy so I’d have something to record onto. I paid whatever their advertised price was that day.

Panasonic reviewed this article for factual accuracy at my request, and I corrected a couple of minor errors.

No material connection exists between myself and Panasonic; Panasonic provides no compensation to me for reviewing equipment and has not influenced me with payments, discounts, or other blandishments to encourage a favorable review.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now