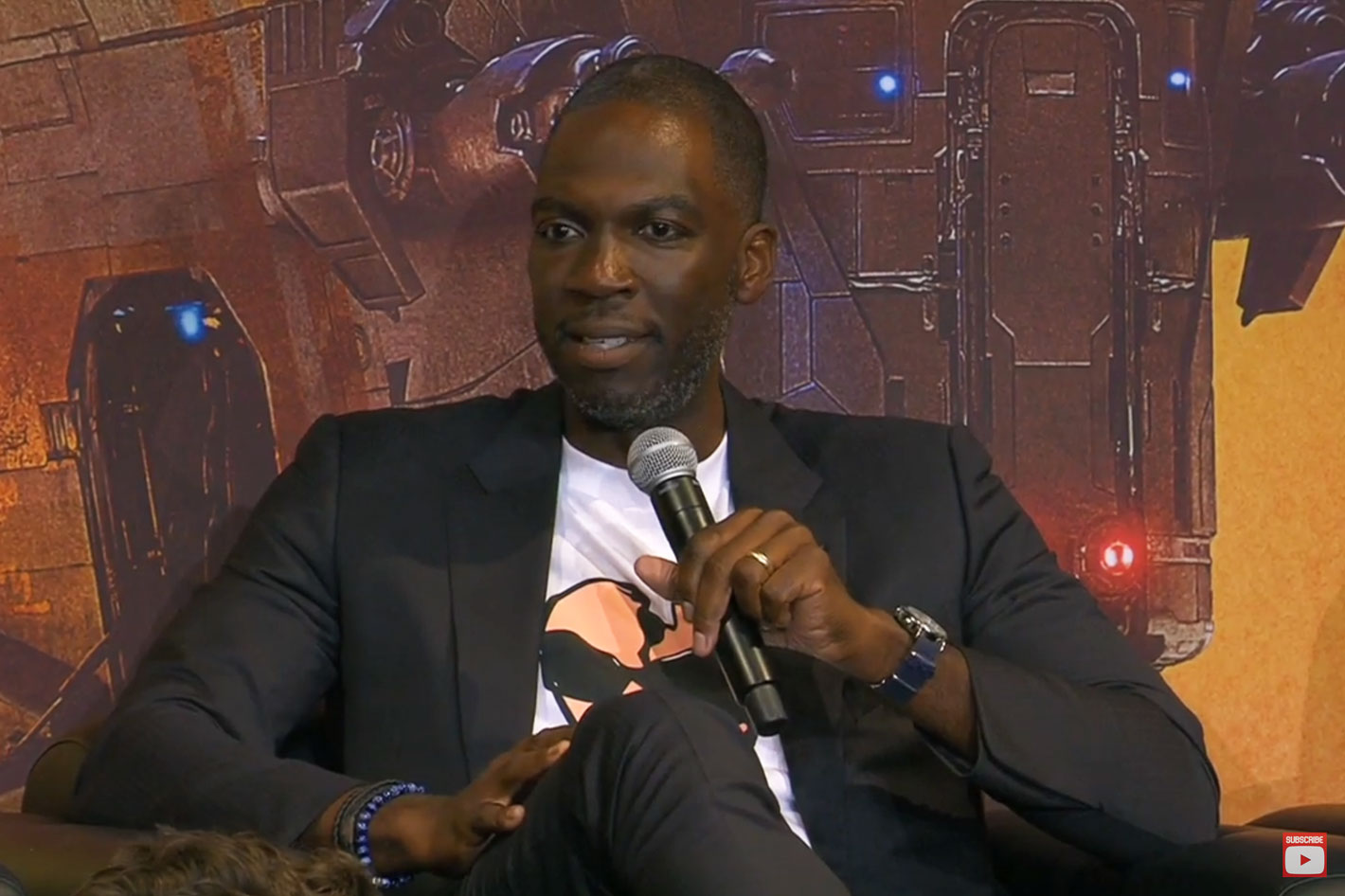

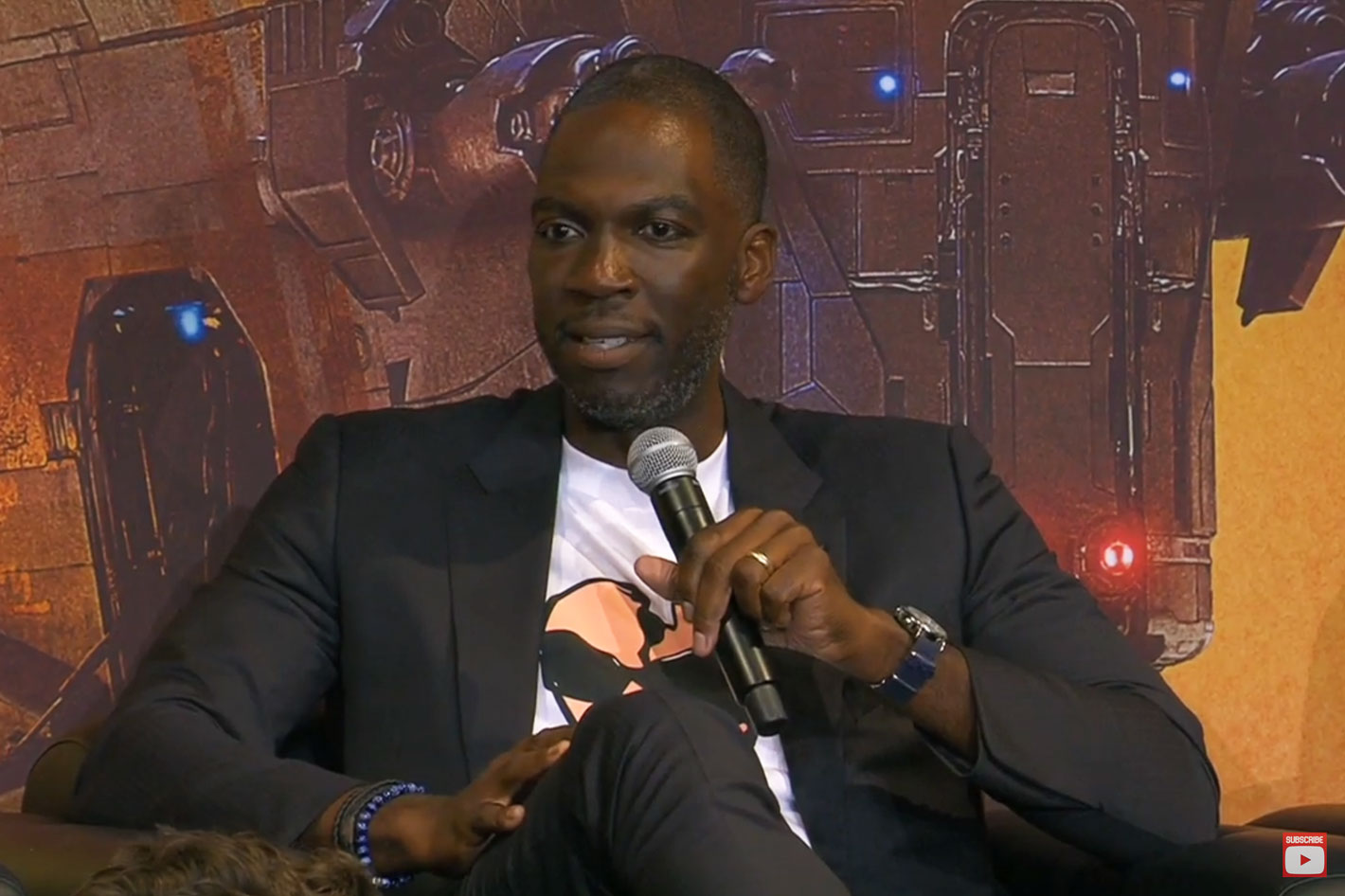

Rick Famuyiwa made his feature film directing debut in 1999 with The Wood. His directing credits include Brown Sugar, Our Family Wedding, and Dope. Famuyiwa also directed two episodes of the first season and one episode of the second season of The Mandalorian. In this interview he reveals how the invitation made by Jon Favreau to join the list of names behind Star Wars The Mandalorian changed his perspective, as he discovered how the new tools made it fun “to create in a way where your imagination can take you anywhere.”

ProVideo Coalition was given this exclusive interview with director Rick Famuyiwa to share with its readers, as part of the promotion of the new field guide for Virtual Production. So, without further ado, lets discover how Rick Famuyiwa got involved with The Mandalorian and Virtual Production.

How did you come to be involved with The Mandalorian as a director?

Rick Famuyiwa: I had some development meetings at Lucasfilm and met Carrie Beck, who was co-producing the show. She later called and asked if I’d be interested in meeting about Star Wars on TV. And I said, “Of course, I would love to.”

I met with Jon Favreau and might’ve been the first person other than Dave Filoni he was talking to about this. He was interested in bringing in different points of view and a diverse set of voices into the world of The Mandalorian and Star Wars. Jon took me through the world and showed me artwork. We just started vibing on our backgrounds in film, and at the end, he asked me to jump in.

Jon started talking about the things that he had been doing on The Lion King and expanding it to its furthest potential. I had no clue what this was going to become. But I was excited to jump in and go for the ride.

How challenging was it to get up to speed on virtual production and the LED volume?

Famuyiwa: It was a crash course and immersion in visual effects. When I started, my understanding was at a “see spot run” elementary level in terms of visual effects. Jon uses visual effects as a big part of his storytelling, which also remains personal and character-driven.

Jon took me through the entire process, starting with VR scouting, setting up shots, shooting, and everything else. At the first meeting, he took me into his world of VR, and it was Pride Rock because he was working on The Lion King at the time. It felt familiar because I had grown up playing video games. It felt natural there, and it was an incredible tool.

So, we built out the worlds, both through the virtual art department and then moving into those environments. I learned how to tell a story with it and use extensive previs. It was an incredible education in visual effects.

Everything got demystified in the process. It became fun to create in a way where your imagination can take you anywhere. I’d say my skills are maybe grade school or middle school level now.

Famuyiwa: You’d go inside these locations with your DP, but unlike four walls around you on a traditional scout, I can go, “Okay, what really would be great is if I can get a camera here.” [Production designer] Andrew Jones would say, “Okay, what if we move the wall over here?” And it’s like okay, perfect.

I come from relatively small films where you constantly have to figure out solutions to problems. To have some of the solutions built beforehand was certainly great. It took some time to get completely comfortable in the environment because a lot of the language was still new to me. Once you see how you can use your imagination, it becomes easier to grasp and use it as a filmmaker.

Did the technology leave room for you to interact with the actors?

Famuyiwa: The most practical benefit of this environment is that you’re in your location when you walk into it. Now you’re just on a set. On the day when you’re shooting, you’re working as if you would on any film in any location. Once the actors got over the trippiness of how the wall moves when the camera moves, it was just great.

It became completely liberating for actors who were very familiar with visual effects. You can work with your actors in such a detailed way versus 10 percent or 15 percent of the time saying, “Well, here’s how the world’s going to look and here’s what going to be over there.” Now, that can be, “Let’s get the scene, make this work, and make it all feel right.”

How did the volume affect your working relationship with the cinematographer?

Famuyiwa: The work starts earlier in the prep process than it would on a typical shoot. We’re thinking about the lighting, even though a lot of that is going to come from the interactive light from the screen. The DP and I are very conscious of where the light is coming from, the shape and direction. We would look at the photogrammetry and think about how the clouds and light are coming through.

For example, in Chapter 2, when we’re in the caves, we spent time deciding where the sun was going to be in relation to the cracks in the ceiling, and how it reflects off of his helmet and everything else. The conversation happened very early, so when you’re on set, you’re really thinking about where the cameras should be and the best way to get the action. You’re able to move in a freeing way. Jon’s calculation is that it’s a lot of work to set up, but once you’re in production, you move at a much faster pace than you would on a typical film set.

Does going into post with more shots completed in camera make editing easier?

Famuyiwa: About 70-80 percent of the shots started at a final level, and then there’s still a lot of stuff that has to be tweaked. A significant amount of this show is shot traditionally with blue or green screen. So, in your cut, you still think about how those things are going to come together and how many shots you’re going to use.

As a director, you got your way on a lot of different things, because everyone knew how important it was to get the first Star Wars series right and feeling cinematic. For me, having everything in place made it easier to fine cut the episode before having to turn over and get more specific for VFX. I could just cut the film as I would anything else because I had most of the information already there.

Famuyiwa: I’ve thought about that a lot. I’d just wrapped my second season episode a week before everything went into quarantine, and it was the last. Post-production happened remotely. It wasn’t as disruptive as it could have been, but at the same time, it got me thinking about the technology and how the volume can enable us to move forward with production.

The ideas behind it minimize your footprint in a way that’s going to be advantageous, particularly in how we prep the show in the VAD in VR. We don’t need a ton of people to get the process going. Then, on the day, you need less of a footprint to build out worlds.

There are still times where we’re in there with tons of extras. But as the animatics or animations on the screen get more interactive, you could use it for deeper background players. We tried to play around with that and see how we could use the sprites in the background. There will be tangible benefits, especially if the cost starts to come down as the technology spreads around the globe.

What should people interested in a career in virtual production study?

Famuyiwa: I’ve gone back to my film school and said this is the future of filmmaking. I’m a lover of film, cinema, and the process of making films. I also love technology and knowing what’s happening or going to happen to help tell a story. I want to continue to dive into this and see how it can be pushed in a lot of different ways.

It puts you in a place that’s so familiar once it’s all done, I feel like it’s approachable. Many filmmakers, once they get involved in it, are going to find value in ways to be creative with it. I’ve been preaching to anyone who will listen is that this method is the way. We shouldn’t be afraid to embrace it. It gives the tools back to the filmmaker in a very cool way.

Where do you see virtual production evolving next?

Famuyiwa: We think about virtual production in terms of larger-budget film and TV projects, but the value could also come from mid-budget and low-budget films that couldn’t afford to be in a lot of different locations. This technology gives you a way to be somewhere too expensive, or where you wouldn’t want to take a crew.

I was developing a project about this hacker. When he hacked into different computers, you would go to these different server locations around the world and see his journey from New York City to Ukraine to Japan. After I did The Mandalorian, I started thinking this was the answer. We could have built those worlds and sent a small crew to each location, do the photogrammetry, and bring it back in and shoot on a stage.

I also got excited about where this could go once it’s less cost-prohibitive. Even as I start to think about my next projects, I think about how to use it in other ways. I’d also love to see other directors get their brains on it.