Quite a lot of the world’s most interesting lens options, including low-cost, high-range, fast zooms, specialities like anamorphics and widely compatible adaptors are much more available in mounts with short flange focal distances. Simultaneously, probably the midrange cinematography world’s popular most lens mount (and if not, certainly the most cloned, from Ursa to EVA) is Canon’s EF, which is far from a short FFD and puts a lot of desirable options out of reach.

Nicotine and caffeine

Let’s imagine a meeting the mid-1980s at Canon’s Tokyo headquarters, doubtless powered by copious quantities of mid-1980s nicotine and caffeine, in which the company’s engineers sketched out the parameters for a new, entirely electronic lens mount. EF was intended to replace FD, and it did, but it was not intended to support lenses for motion picture work – and it did that too. Now, EF turned out to be crucial to the rehabilitation of autofocus from the professional gulag of amateur-hour camerawork, but now even Canon itself is stepping back from the design in favour of RF, cognizant of the benefits of shallower FFDs.

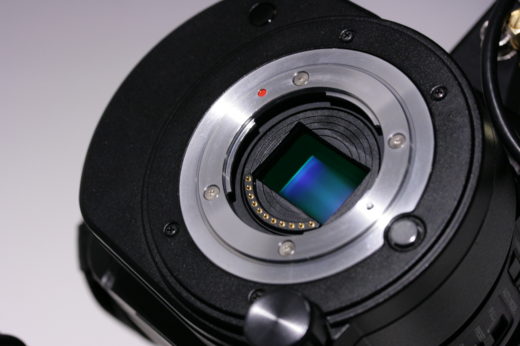

Even beyond the FFD issue, EF is not well-suited for motion picture work. It’s a bayonet mount in which metal slides against metal under spring pressure, raising the spectre of gradually drifting FFD as parts wear. In its original application, it doesn’t need to maintain an accurate FFD; most autofocus systems (with the notable exception of something like a DJI Ronin 4D or various stereoscopy-based standalone systems) do not operate by determining the distance to the subject and setting the lens to that distance.

Designing to avoid precision

An EF-mount autofocus system simply moves the focus around until the region of interest is sharp. It doesn’t care what that distance actually is, which is why it’s not usually possible to somehow jack a manual follow focus device into a Canon EF lens system and set a distance. Some EF glass has reasonable repeatability, in the same way that some stills zooms are reasonably parfocal, but it’s not really by design. So long as the lens has some beyond-infinity travel, the precision of the FFD need only be approximate.

But that’s only a problem for the very high end. The biggest problem with EF is that it’s not the right size and shape. OK, it’s actually something like the same size and shape as LPL, but EF cameras can accommodate almost nothing but EF lenses. Only Pentax K, Nikon F and an extremely small minority of specially-designed PL-mount lenses (such as the SLR Magic Anamorphot Cine set) can be adapted.

It’s no secret why designers choose EF. In 2014 Canon promoted the fact that it had manufactured one hundred million of them, and that’s not even including compatibles from the likes of Sigma and Tamron. As such, manufacturers keen to keep the total system cost of their cameras down by leveraging a purchaser’s existing lens investment tend to reach for EF mounts, even though, as we’ve seen, that isn’t necessarily an idea that makes a lot of objective sense in any other way.

Pick a lens mount, any lens mount

So, a shallower mount would make sense. Exactly which shallower mount, though, isn’t quite so obvious. LPL is hard to recommend. While it is effectively the movie industry’s idea of a mirrorless mount, in the same way as RF, Micro four-thirds and others, LPL could really have been a little shallower; at 44mm, it actually has the same flange focal distance as EF itself, so all those shallow-mounted designs, built for Sony E and Micro Four-Thirds mounts, remain out of reach to LPL cameras.

It’s no surprise that DJI’s DL-mount has a microscopic FFD of just under 17mm, keeping things small and light as required for the gimbal, and simultaneously somewhat easing lens design considerations. Fujifilm’s X mount is 17.7mm, Sony E is 18 and Micro Four-Thirds is 19.25, making crucial things like PL and EF easy. There need be no huge sacrifice to make this work; designers have found ways to fit a Super-35mm-sized sensor behind a micro four-thirds mount, and even to include mechanical ND filters. Even Fujifilm’s G mount, for its galaxy-engulfing GFX medium-format cameras with sensors big enough for two men in overalls to carry across an alleyway during a chase scene, has a flange depth of only 26.7mm. Shallow and huge can be done; perhaps the best approach was Sony’s brief dalliance with its 19mm-depth FZ mount.

The simplest approach is a simple bolt-down mounting surface, so long as it’s sufficiently close to the sensor. Still, it’s well past time that camera manufacturers realised that throwing an EF mount on there, or even an interchangeable EF-PL option, excludes a lot of affordable, high-performance, desirable lenses from use on that camera. In a situation where manufacturers are increasingly struggling to differentiate cameras on picture quality, flexibility is a bigger deal.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now