The music industry began reviving vinyl records in 2007. More recently, Kodak revived analog Super 8mm film production. Even Polaroid-branded instant film cameras have returned. As a video producer, do you miss the softer, standard definition interlaced image with a heterodyned color-under system, Y/C ±688 kHz dub, classic head switching visual effects in select models, visual dropouts (different from school dropouts), TBCs (the original time base correctors without full-frame synchronization), advanced vertical sync and optional subcarrier feedback? They were part of Sony’s U-Matic format. Do you long for the nostalgic days of A/B roll editing and accomplishing the coveted match-frame edit? Or would you prefer a modernized, digital 4K version of the 3/4” U-Matic tape format, with HDMI and SDI inputs and outputs? Ahead is a brief history of U-Matic, including a product video of the VO-3800 portable recorder from 1974, with its external color playback adapter. And maybe we’ll see U-Matic re-introduced in a week from now

A brief history of the U-Matic format

Here’s the Wikipedia first paragraph, followed by my comments:

U-matic is an analog recording videocassette format first shown by Sony in prototype in October 1969, and introduced to the market in September 1971. It was among the first video formats to contain the videotape inside a cassette, as opposed to the various reel-to-reel or open-reel formats of the time. Unlike most other cassette-based tape formats, the supply and take-up reels in the cassette turn in opposite directions during playback, fast-forward, and rewind: one reel would run clockwise while the other would run counter-clockwise. A locking mechanism integral to each cassette case secures the tape hubs during transportation to keep the tape wound tightly on the hubs. Once the cassette is taken off the case, the hubs are free to spin. A spring-loaded tape cover door protects the tape from damage; when the cassette is inserted into the VCR, the door is released and is opened, enabling the VCR mechanism to spool the tape around the spinning video drum. Accidental recording is prevented by the absence of a red plastic button fitted to a hole on the bottom surface of the tape; removal of the button disabled recording. As part of its development, in March 1970, Sony, Matsushita Electric Industrial Co. (Panasonic), Victor Co. of Japan (JVC), and five non-Japanese companies reached agreement on unified standards.

What the first paragraph neglects to mention (although Wikipedia goes on to say later) is that U-Matic was initially intended to be a consumer format. Sony’s initial intention was not for U-Matic to be used for professional or broadcast use. In the consumer market, U-Matic was somewhat of a sales failure due to the high manufacturing cost and resulting retail price of the format’s first VCRs (video cassette recorders). But the cost was affordable enough for industrial and institutional customers, where the format was very successful for such applications as business communication and educational television. As a result, Sony shifted U-Matic’s marketing to the industrial, professional, and educational sectors.

U-Matic saw even more success from the television broadcast industry in the mid and late 1970s, when a number of local TV stations and national TV networks used the format after its first portable model, the Sony VO-3800, was released in 1974.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HytBVRUUfu4

Sony’s launch of the VO-3800 Portapack in 1974

This model was a first step towards the era of ENG (Electronic News Gathering), which eventually made obsolete the previous 16mm film cameras normally used for on-location television news gathering, which later needed to be developed and placed on a telecine for play to air. However, an essential missing piece was missing to allow for the use of U-Matic for direct playback on air, was the TBC (time base corrector).

In my recollection, the first TBC to work with U-Matic was the Sony BVT-800 (shown above) and initially cost ±US$10,000. As the decades progressed, TBCs slowly dropped in price even to under US$1,000 on a PCI card, which would be installed into a computer or external enclosure. Some later U-Matic decks would eventually earn their wings with an inboard TBC, as described ahead in this article.

Industrial vs Broadcast

U-Matic (and later U-Matic SP, superior performance) models were categorized as either Industrial (with a VO- prefix followed by 4 numerals) or Broadcast, with a BVU- prefix followed by 3 numerals. More examples about models ahead in this article.

See definition 21 of the word broadcast in my 2011 article, Do you work in the broadcast industry? What does “broadcast” mean?, illustrated above, to understand why Sony designated the Industrial and Broadcast lines this way.

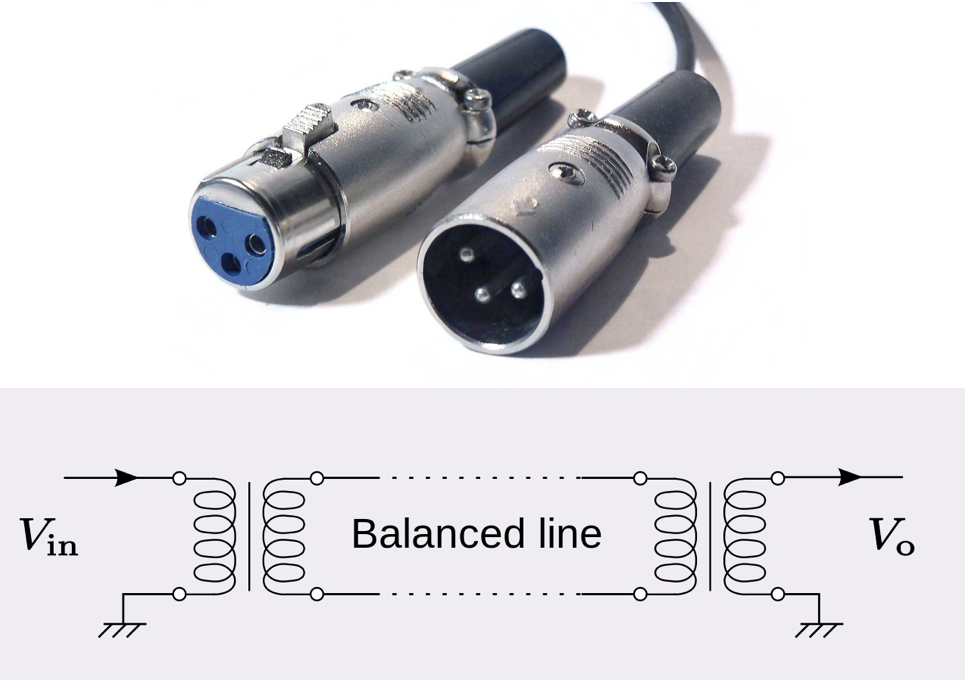

In the portable line of U-Matic recorders, I remember and used the VO-4800, the last industrial (non-“broadcast”) model to force us to use an unreliable, unbalanced 3.5 mm TS (tip sleeve, see TS/TRS/TRRS/TRRRS: Combating the misconnection epidemic) to connect microphones.

The subsequent model I recall was the VO-6800 (shown above), which was the first industrial (non-broadcast) model to be blessed with balanced XLR inputs to connect microphones cleanly and more reliably.

See my recent Balanced audio: benefits and varieties, illustrated above.

Finally, the last industrial portable U-Matic recorder I recall (which was U-Matic SP) was the VO-8800. This one not only had balanced XLR audio inputs, but was also the first and only U-Matic portable recorder that could accept Y/C ±3.58 MHz (in NTSC models) or Y/C 4.43 MHz (in PAL models) from its multi-pin input from compatible cameras. Those cameras mainly offered this Y/C output for the S-VHS recorders that began becoming popular in the same era, but offered the same benefit over composite video as it did for S-VHS and the analog version of Hi-8mm videotape. Considering that the U-Matic recording —since the very beginning— was always Y/C (luminance separate from chroma) on the tape, this allowed bypassing the Y/C separator, conserving better image quality. Since commercial U-Matic machines did not offer direct color (the way 1” open reel machines did), the original ±3.58 MHz chroma (in NTSC models) or ±4.43 MHz chroma (in PAL models) was heterodyned down to 688 kHz. Connecting separate Y and C to U-Matic separately was a first step towards what was later used on true component analog systems and recording formats, including Betacam (SP) and MII.

Many third-party TBC manufacturers offered receiving the Y/C 688 kHz directly from the 7-pin dub output of U-Matic editing decks to preserve more picture quality. Those included the JVC KM-F250, which offered Y/C 688 kHz and even component analog output, which I used in many systems I designed as hybrid to a component analog video mixer (“switcher”).

Kits were offered by ingenious companies to add Y/C ±3.58 MHz (in NTSC models) or Y/C 4.43 MHz (in PAL models) outputs to many U-Matic models. This was useful even to connect Y/C directly to a monitor or TV set with a 4-pin Y/C input. Many of those monitors and TV sets labeled the Y/C input as “S-Video” for Separate Video, and it was the same as Y/C.

(There was an independent facility in California that would offer to modify certain U-Matic model(s) to record direct color at a much higher tape speed. Those direct color U-Matic recordings could only be played on similar converted machines, and were not compatible with standard U-Matic machines. If any reader remembers the name of the California facility, tell me in the comments so I’ll update this.)

Desktop models

The very first consumer desktop U-Matic VCRs (video cassette recorders) were top-loading. The VO-1600 even had a rotary tuner built-in to record shows off of the air, UHF and VHF. The first professional U-Matic desktop models were also top-loading (even the editing models). I personally used the VO-2860 editing recorder and later models.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ttCiGsBxJnA

There was a prior VO-2850 model (illustrated above, ±US$6,000) that I didn’t use personally.

Then came the first “industrial” VO-5800 feeder and VO-5850 recorder/editor which were front-loading. Sony did not offer timecode option for these industrial models, but they did for the next generation (and last generation) “industrial models”, the VO-9800 feeder and the VO-9850 editing recorder, shown below.

These were U-Matic SP, superior performance. The optional timecode cards cost well over US$1000 each. The BKU-704 card was a timecode reader for the VO-9800, and the BKU-705 was a timecode reader generator card for the VO-9850.

The NTSC version of the BKU-705 (shown above) had a selector switch for DF/NDF (drop frame/non-drop frame). The PAL version of the BKU-705 had no such switch, because the drop frame/non-drop problem frame fortunately never existed in PAL.

Some of the “Broadcast” U-Matic SP desktop models offered optional, internal TBCs, like the BVU-900 feeder and BVU-950 (shown above). These BVU series were capable of recording or playback without visible head switching noise.

Many of the desktop models had a built-in jog/shuttle, i.e. the big knob you’ll see in the lower right, above. The jog function would allow moving forward or backwards frame-by-frame. The shuttle would allow variable speed forward and back. Only when using a mini U-Matic tape, could the maximum speed shuttle be reached, which many of my friends and I would refer to its “C’mon speed!”. This maximum speed was not available with full-sized U-Matic cassettes in my experience.

With all U-Matic editing, we needed to know the difference between Assemble Editing and Insert Editing. For more sophisticated editing, we would first record the tape with a black signal, which was 7.5 ire in the NTSC countries in the Americas, zero IRE in all PAL countries and in Japanese NTSC. That was called blacking or striping the tape. After doing that, we were free to do audio or video inserts, or even split edits, where the audio or video could enter at a different time.

Even though the non-editing players like the VO-9000 were not intended by Sony to be used as source machines in editing systems, ingenious developers like Videomedia (originally of San José, California) promoted viable workarounds to make them work frame accurately, via their V-LAN system, an optional Sony RS-232 card and a tiny modification of said card (cutting a resistor). This worked with any editing system that used the Videomedia V-LAN, including the Mickey, OZ and VLC-32, as well as many other non-Videomedia linear editing systems that licensed the V-LAN system. To achieve frame accuracy with a Sony U-Matic deck which did not offer the third audio track for timecode required either using audio channel 1 for timecode (leaving only channel 2 available for actual audio) or modifying the deck to allow access to the third audio channel. Either way, the actual timecode reading needed to happen externally of the deck, i.e. with an optional timecode card inside of the V-LAN.

Summary, conclusions and disclaimer

I have no inside information as to whether Sony plans to announce a revival of U-Matic at NAB 2018, either with a classic analog style, digital version or some hybrid. If someone at Sony is reading this article, knows that Sony will be reviving U-Matic at NAB 2018, and suspects that some other Sony employee leaked the information to me, I assure you: That is not the case. In that case, it’s just a coincidence.

If someone has more royalty-free U-Matic photos to add, please contact me and I’ll add them.

Today is April 1, which marks NAB (National Association of Broadcast month in Las Vegas, Nevada) month. In the United States, today is also April Fools Day, so I thought it would be a good day to salute Sony for creating the format with which many video professionals first learned to produce, edit and communicate with motion pictures. I know that the equivalent to April Fools Day in Spain and Latin America is on December 28, and the day may vary in your country.

Upcoming articles, reviews, radio shows, books and seminars/webinars

Stand by for upcoming articles, reviews, and books. Sign up to my free mailing list by clicking here. Most of my current books are at books.AllanTepper.com, and my personal website is AllanTepper.com.

Si deseas suscribirte a mi lista en castellano, visita aquí. Si prefieres, puedes suscribirte a ambas listas (castellano e inglés).

https://play.radiopublic.com/beyond-podcasting-beyondpodcastingcom-G4bBZ1

Suscribe to his BeyondPodcasting show at BeyondPodasting.com.

https://play.radiopublic.com/tu-radio-global-turadioglobalcom-Wk2bAY

Subscribe to his Tu radio global show at Turadioglobal.com.

Listen to his CapicúaFM show at CapicúaFM.com or subscribe via Apple Podcasts, Radio Public or Stitcher.

Save US$20 on Project Fi, Google’s mobile telephony and data

Click here to save US$20 on Project Fi, Google’s mobile telephone and data service which I have covered in these articles.

FTC disclosure

No manufacturer is specifically paying Allan Tépper or TecnoTur LLC to write this article or the mentioned books. Some of the other manufacturers listed above have contracted Tépper and/or TecnoTur LLC to carry out consulting and/or translations/localizations/transcreations. Many of the manufacturers listed above have sent Allan Tépper review units. So far, none of the manufacturers listed above is/are sponsors of the TecnoTur , BeyondPodcasting or TuNuevaRadioGlobal programs, although they are welcome to do so, and some are, may be (or may have been) sponsors of ProVideo Coalition magazine. Some links to third parties listed in this article and/or on this web page may indirectly benefit TecnoTur LLC via affiliate programs. Allan Tépper’s opinions are his own.

Copyright and use of this article

The articles contained in the TecnoTur channel in ProVideo Coalition magazine are copyright Allan Tépper/TecnoTur LLC, except where otherwise attributed. Unauthorized use is prohibited without prior approval, except for short quotes which link back to this page, which are encouraged!

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now