There’s a reason low-rent independent short films often lack dynamic staging, feeling static and limited in their use of locations, and it’s not lack of space – or at least not lack of space in front of the camera.

It’s hard, sometimes, not to sink into a state of curmudgeonly finger-waggling any time someone more than fifteen years younger than oneself scoffingly claims that a given scene can be lit with pocket-sized lights running on battery power. It’s particularly difficult to take when they’re right; after all, cameras are now routinely capable of shooting at thousands of ISO with acceptable noise, and lighting with better-than-tungsten efficiency is much more affordable than small HMIs ever were. That hundred-watt open-faced LED still can’t light that whole building, you young whippersnapper, but taking everything into account it’s quite possible that the world really is effectively four stops brighter than it was around the turn of the century.

Less power, less gear. Same amount of space overall.

The amount of power and gear required has collapsed massively, and we don’t really have to take any particularly unusual measures to achieve it. What hasn’t collapsed is the required size of the setup required to create any given scene, because humans are just as big as they ever were and the inverse square law works just the same way it ever did. This means that certain things still can’t be done with an amount of gear we can happily backpack on the subway, and that’ll remain the case regardless how fast cameras become.

If this seems completely elementary, consider this example, provoked by a real world situation which must, sadly, remain anonymous, directed by someone whose experience began and ended with lights you can pick up with one hand.

Let’s say we’re covering the first half of a dinner conversation, at night. Rake the background with a hard steel green, because night is green this week, and position the big, slightly warm, very soft key just out of frame. Assuming we’ve put a suitably symmetrical-looking actor in an appropriate location, it starts looking like a movie even before we’ve set the backlight. This is the sort of thing that people tend to figure out fairly quickly, and it takes advantage of all the new technologies we’ve been discussing so far. Between f/1.2 lenses and 3200 ISO cameras, we can light that with a mating pair of glow-worms.

Sit very still, please.

But anyone can light a closeup. Let’s say we’re interested in showing the talent getting up from the table, though; in that case, things change. If the diffusion is really close, even leaning away from it is likely to betray how nearby it is as exposure plummets precipitously. To fix that, the diffusion has to get bigger and move further back. Turn this into a scene in which our heroes get up from the table and continue their conversation as they leave the building, and it has to get much bigger and move much, much further back.

We’re still free to leverage the huge sensitivity of the camera and the huge efficiency of the light, but we still need giant diffusion. And somewhere to put it, and big stands to put it on, and several equally large flags to control the monster we’ve now created, as it projectile-vomits photons all over the hemisphere. We need a group of people in jeans and check shirts to rig and de-rig it all, food for them to eat, and somewhere for them to park. Saving 75% on power consumption is nice, but it starts to seem positively trivial in the context of merely securing a location with elevators big enough to get everything where it needs to be.

In the end, space outside the frame to set up is not a new problem, nor one from which anyone is completely immune. Let’s consider what was probably one of the largest single lights ever used in a feature film, the gargantuan 100kW SoftSun specially built for First Man. Lighting night exteriors – which is not quite what was being done for the lunar surface scenes, but give me some rope here – has always been tricky. No matter how large a light we use, it will always fall off to darkness in the end. The key issue isn’t the distance we want the actors to move; it’s the ratio between that distance, and the distance between the actors and the light. Lights that size exist to maximise the actor-to-light distance and thus minimise visible falloff. The power consumption is one downside. The other is the construction crane and quarter mile of space, which doesn’t change even if we find a magical way to build a SoftSun that can be powered by a hamster in a wheel.

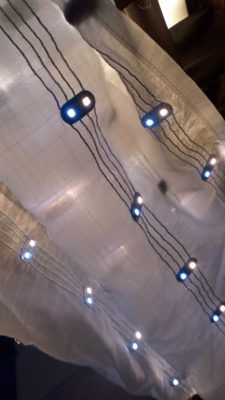

That’s not to say modern technology hasn’t given us anything that lets us shrink setups. The flexible light panels we can now rig into diffusion frames are unimaginably more efficient than firing a fresnel into a piece of fabric and hoping some of the photons make it out the other side. They’re also vastly faster, easier and lighter on gear and people. But unfortunately, if we want someone to be able to move around a scene without the exposure varying in a way that only makes sense if the sun is really nearby, a certain amount of size and space is always going to be involved.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now