It is widely accepted that RCA was the preeminent broadcast supplier in the early days of television. The RCA public relations machine would have everyone believe they were the only supplier. In fact, they did have the market cornered since they were also known for their “soup to nuts” solutions for radio. With a customer base of radio stations in the United States entering the television market for the first time, they had built in demand for their products. However, there were other suppliers out there and in the field of television cameras, the Philo T. Farnsworth organization was attempting to be David to RCA’s Goliath.

The 1936 Olympics games in Berlin, Germany, would be the first international television sports event. Despite all the hoopla being spewed out by the German propaganda machine during the games, the television pictures being transmitted and recorded were not entirely of German design. Up until the early 30’s, Germany was attempting to improve mechanical television to a watchable state. The 180 lines at 25 frames was to have been the bridge between the mechanical system and fully electronic television. Germany claims the “world’s first electronically scanned television service” beginning in 1935. The two German manufacturers represented – Fernseh AG and Telefunken – did indeed design the equipment to a large degree. However, the internal cores of the cameras (that were now electronic) were designed by U.S. Companies – Farnsworth’s Image Dissector tube was at the heart of the Fernseh AG’s units and Vladimir Zworikin’s Iconocope tube converted the pictures from photons to electrons in the Telefunken cameras.

Following a trip to Europe in 1934, Farnsworth, the “wunderkind from Utah,” secured an agreement with Fernseh A.G. to exchange television patents and technology to speed development of stations in their respective countries. In wouldn’t be until 1939, after the lawsuits generated by RCA finally conceded that Farnsworth invented the camera that was the basis of electronic television, that licensing agreements would be generated and for the first time David Sarnoff would be paying royalties.

RCA was active with Telefunken who licensed and demonstrated a camera influenced by the Iconoscope tube. In licensing the Iconoscope technology from RCA Telefunken made improvements in the camera technology, but did not use the smaller super iconoscope as others have reported.

There is some conjecture regarding the replacement of the iconoscope tube in Telefunken Olympic camera cannons. In a document written by Christine Heimprecht “Fernsehkamera – Dr. Walter Bruch und die Olympiakanone” the claim is made the use of a “superikonoskop” was developed and used in the Telefunken cameras at the Olympics. However, there is documentation that the improved iconoscope wasn’t available until the later days of World War II and was developed for use in television controlled guided weapons. [Please see Peter Scott’s entry on the Early Television Foundation’s website.]

According to the documentary “Television Under The Swastika – Unseen footage from the Third Reich” (Spiegel TV 1999), there were only three electronic cameras (2 Telefunken and 1 Fernseh A.G.) available for the games assigned to the Olympic Stadium. A control room had been designed and built at the stadium site so there was no “OB” (Outside Broadcast) unit. Any camera that could generate an electronic signal was probably connected to the lines that criss-crossed the Olympic venues and sent back to the control room.

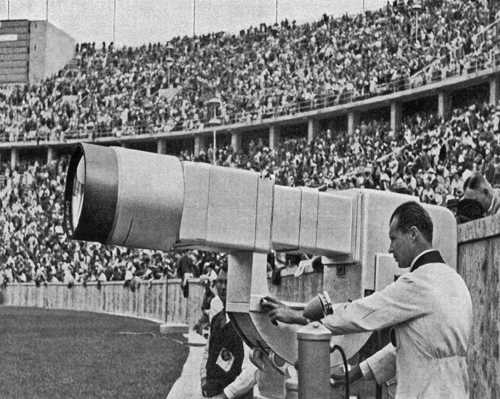

The two Telefunken units had limited mobility and spent the “full 16 days in largely fixed positions on the south side of the Olympic Stadium at track level.” Other than changing lenses and panning and tilting, there couldn’t be a lot of movement. There was nothing like the miniature cameras, zoom lenses, mobile camera cranes or flying cameras we are familiar with now. Bobby Ellerbee from the “Eyes of a Generation” website states, “…the Telefunkens appear to have zoom lenses, but they’re not. There were several fixed focal length lens options that could be changed out (a 2 man job), and we can see an example of that in the telephoto lens shot. They have placed the focus mechanism on the outside of the camera instead of inside, and are already using cradle heads instead of friction heads.”

The third camera, the Fernseh, A.G. unit, located at the Olympic Stadium is shown here from a “Wireless World” picture as part of their August 21st, 1936, coverage of television at the games. There is no reference to it directly but the assumption is made that it was fed through the control room operating in the Olympic Stadium. It spent 13 days at the Olympic Stadium and 3 days in Dietrich Eckart Open Air Theatre. Ellerbee describes the Fernseh AG unit as a “roving camera.” Given the available pictures that would seem to be the case.

Fernseh AG did have an OB van – of sorts. It was referred to as the “intermediate-film process.” This was a unique machine. The unit had a 35mm film camera installed on its roof. On the top of the camera was a feed reel of 1300 meters (about 4200 feet). The camera would have to be restricted in its pan and tilt movement due to the process involved. The exposed footage passed out of the camera through a light-tight conveyer, down through the pedestal and the roof of the van into a processing tank.

The film “was immediately developed, fixed, washed and given a preliminary dry. The film negative whilst barely dry, was scanned by a flying spot scanner and turned into a positive for transmission over the air.” The “flying spot scanner” was equipped with a Farnsworth image dissector camera. Now as an electronic signal it could also be connected to the lines available at the Olympic venues and sent to the stadium control room. “Fernseh overcame the Image Dissector’s need for very high light levels to perform adequately” by providing a consistent and adequate light via the scanner.

In reviews, it is apparent the sound track on the intermediate-film process suffered due the haste to get in on the air in minimum time. Since the telecine point took place when the film was still damp from the drying stage of the processor, the sound track appeared to be impaired by “the rapid developing, fixing and drying processes.”

Wireless World alludes to a “long film transmission” to recap the day. It does not stipulate if the film originated with the Fernseh intermediate film truck. It just states the films “were not specially selected for television purposes.”

In addition to the “Intermediate Film Camera,” there is also a reference to an Iconoscope based camera that is not part of the Telefunken complement. It was built by German Post Office engineers and was stationed at the Swim Stadium for the duration of the games.

Since all the television facilities were operating at 180 lines at 25 frames a seconds, there is no reason why the Fernseh units couldn’t be tied into the control room and cross-cut with the Telefunken units. Although, according to David Large, author of the “Nazi Games: The Olympics of 1936,” “They used three different types of TV cameras, so blackouts would occur when changing from one type to another.” We don’t know that the Germans had figured out how to lock to one sync source to lock each camera. It wasn’t until 1951 that RCA started marketing their Genlock unit and caught up with the process of locking two disparate sources.

Two cables were energized for the telecasts to feed the Witzleben television transmitter from the opening ceremony to the closing ceremony with a main and a backup cable.

At the receiving end were various installations. Up to the beginning of the Olympics, television technology was being pushed by politics in the interest of showing how the country was making strides in improving daily life for the German people. Though the only people who had television receiving sets were engineers and some of the political elite had their own sets. However, “there were no television receivers on sale to the general public.”

“It was sometimes harder to get a ticket to get into one of the television rooms in Berlin than it was to go to the stadium itself,” according to author David Large.

The technology had progressed to the point that an upgrade to 375 lines interlaced could have taken place ahead of the games. But 180 lines non-interlaced 25 Hz frame rate was a well engineered legacy left over from the mechanical television system age. The manufacturers of television receivers were reluctant to suddenly make major upgrades to 375 lines with so little time to prepare for it. In addition, the Wizleben/Funkturm transmitter was fire damaged less than a year from the beginning of the Olympics. It was replaced by another 180 line unit to insure its readiness for the games.

Eventually, the Germans upgraded to the 441 line rate in February, 1937. “Curiously, only a few weeks after RCA had also increased to 441 lines.”

https://youtu.be/3exBWIwrvsE

The prewar Olympic telecasts that have survived over the decades since television’s introduction to Germany represent a sampling of the barely discernable to better than passable of the era. However, it did provide substantiation to the government promise going forward – it had succeeded and claimed credit in bringing television to the country – and to the world. But what else was true was that it was based on work going in other countries, notably Great Britain and in America, and how much they contributed regarding invention and innovation. Television was already a blossoming international industry. But with all its claims of being first, Germany’s national radio and television organizations ceased operation in the fall of 1944.

In an article written in 2008, Chris Bowlby of the BBC explained how the Olympic torch relay was created as an innovation of the Berlin games “to project the image of the Third Reich as a modern, economically dynamic state with growing international influence.”

In less than five years, all worldwide work on television would be halted as the world was plunged into dark times. Borrowing from Bowlby’s article, “No matter how great the emphasis on the torch as a bright sporting symbol… amid the political wrangling and media hype, less welcome historical ghosts are running alongside.

It can be said the quote is apropos for television as well.