The People’s Court has been a mainstay of American television for decades. Millions tune in daily to watch Judge Marilyn Milian hear litigants’ claims and preside over real-life cases. Originally aired in the 1980s, the show was revived in 1997 to much acclaim, earning several Daytime Emmy awards and nominations.

The show is typically filmed before a live audience, focusing on two to three cases per episode for each of the season’s 150 episodes. All of that changed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Restrictions on travel and gatherings meant that The People’s Court needed to go virtual. Supervising producer for post-production Kelly Irvine, supervising editor Jamie Billett, and senior editor Scott Ratner took Adobe behind the scenes to talk about how they remotely produced a season of this popular, long-running television staple.

What did your filming and editing workflow look like before the pandemic?

Jamie: We normally shoot all cases in a studio environment. One fun fact is that when The People’s Court was relaunched in 1997, we used the original set from the Judge Wapner days. It’s just so iconic, and it’s seen very few changes since then. The way we film is a bit like live sports. There are no takes. It’s just live feeds running into a control room.

Kelly: The director creates a line cut in the control room, switching between four cameras on the fly. Editors will trim each case for time and clarity, creating a story that’s easy for audiences to follow. They might work with individual camera footage to cover edits, but the bulk of their edit is based on the director’s line cut.

Normally we’ll record a months’ worth of shows at a time, covering 10 cases a day and seeing a hundred litigants. We select the cases that will resonate most with audiences and take four weeks to edit those into 15 or 20 episodes.

How did everything change when the pandemic hit?

Jamie: We were only one week away from the end of the season when we had to shut down. At first, we just concentrated on finishing up episodes. We’d already started adopting some remote editing workflows. People could work from home once a week using a proxy of the line cut. But trying to completely deliver episodes from home was a huge challenge. We’d remote into our computers and edit on our Avid workstations, but it was hard to share work and go through cuts with screen sharing. As soon as we hit our summer hiatus, we went straight into trying to figure out how to get the next season done, both from a filming and production aspect.

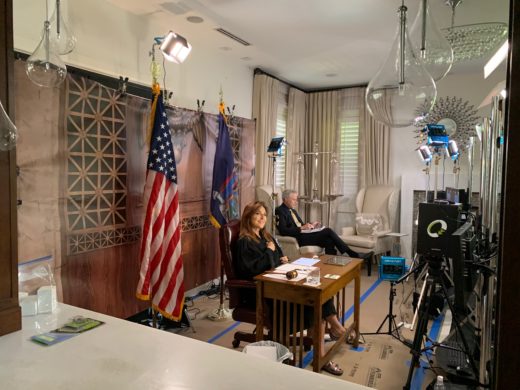

Kelly: We knew we had everything that’s important to our audiences: engaging stories, interesting people, and Judge Marilyn Milian. But how do we pull everything together without our studio?

Jamie: Scott and I started experimenting with Zoom, Skype, and other video conferencing solutions, but there was no way to record full-frame and full-resolution video for each person. We talked to folks doing talk shows remotely, but they were just recording one person at a time, so they shipped professional camera setups. We needed to film multiple people in every case and film dozens of cases every week. We settled on Quicklink to connect and record the streams from our professional cameras filming the judge and the rest of our cast, as well as the phone or laptop cameras connecting our litigants.

If you’ve ever been on a video conference, you know that streaming video can sometimes have problems with quality, particularly when it comes to audio. So we shipped each litigant a cheap commercial camera to get a second, offline video source. Litigants shipped the cameras back after filming their case so that we could pull the footage. The visuals weren’t always usable—we called the litigants to walk them through setup, but still got a lot of cameras cutting off half the face or pointed at plants. But we could usually pull the audio to have clearer sound, and that helped save a lot of cases.

Kelly: Our audiences knew that we were filming remotely, so they were a lot more forgiving in terms of visual quality. But we still wanted to maintain the storytelling quality expected from our brand.

How did the socially distanced shooting schedule change the editing workflow?

Jamie: It was a huge change. We went from working with a line cut to editing together footage from up to nine cameras. We had the streamed video from the participants of each case. There was a view of the iPad where the judge would look at evidence. Then we had to add in footage from the cameras shipped back from litigants. We added two assistants to keep up with the increase in work, but the number of editors stayed the same.

When we went fully remote, we decided to make the switch from Avid to Adobe Premiere Pro. The Multicam editing workflow made it much easier to keep track of all of the footage. We easily replaced shots or use the audio from the offline camera to replace garbled streaming audio. If sync was off for the streamed footage, we adjusted that in the Multicam source.

Was it a sudden decision to switch to Adobe Premiere Pro?

Scott: We had been talking about moving to Premiere Pro for a while, and with the remote workflow, it made the most sense. One of the biggest advantages for me is the integration with Adobe After Effects. We’ve used After Effects to handle the graphics on the show for 20 years. There have obviously been changes—the design and colors have changed, we upgraded resolutions—but otherwise they’re pretty much the same.

We have a lot of text and titles that change for every case. At the start of every case, we introduce the two sides and the on-screen text will say something like, “John Smith, Plaintiff, Suing for $500”. I do maybe 90 of these per week. Sometimes I need to redo text for spelling mistakes. Or maybe originally there was a countersuit, but it got dropped during the trial and eventually edited out entirely for time.

Now that we’ve switched over to Premiere Pro, I don’t have to worry about spending time re-rendering titles for editors. We’re also taking advantage of Motion Graphic Templates so that editors can start to change some of this text themselves. It seems trivial, but it eliminates a lot of time that I normally spend going back and forth to get graphics right. I can spend more time building the final show by letting editors handle it themselves.

Jamie: Premiere Pro gives us all the tools that editors need to take care of things like sweetening the sound or doing some color correction and grading. We don’t have time or budget for sound or color post departments. Color and sound are normally taken care of in production in the control room with colorists and a sound mixer and we in post don’t have to touch it. But because of remote cameras now, the production crew doesn’t get to correct them, so we end up doing that work in Premiere Pro. I also use the Lumetri Color panel to create quick masks and highlight a line of text in the evidence and make it easier for our audience to follow.

Did you see any changes in the cases themselves during this remote filming process?

Scott: You know it’s interesting because before, we might have identified a possible litigant in Kansas City, but they couldn’t afford to miss work or find childcare to fly to Connecticut for a day, so we’d have to move on to another case. But with everyone filming remotely, it really didn’t matter where they were.

Kelly: We do want to get back to the studio eventually. It makes things so much easier from a technical perspective to get through the sheer volume of litigants we see every day. We won our third EMMY in the time of Covid, and we’ve been picked up for another season, so we’re excited to continue our work.

For more information on their workflow, watch the Remote Production Conference keynote – The People’s Court: Managing the Plaintiff and the Defendant Remotely