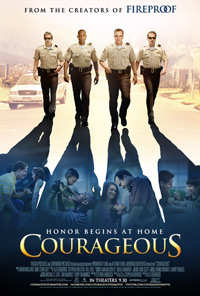

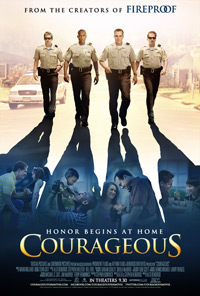

Last October, I had the rare opportunity to edit a feature film called “Courageous,” which is in theaters now. “Courageous” was the number one new movie the weekend it opened (September 30th) and the number four movie over all and it’s stayed in the top six for the last three weeks, with its per-theater box office at the number one spot for two weeks, and still at number 2.

You can download the trailer here.

This article and the follow up will discuss the entire workflow of getting the R3D files from the camera, archiving them, transcoding them, organizing the files, making editing decisions with the director, and eventually, delivering the edit and raw files to PostWorks in NY and following the entire on-line post-production workflow getting the RED files and a Final Cut Pro 7 sequence up on the big screen in over 1,200 theaters nationwide.

Sherwood Pictures’ last theatrical release was the number one independent movie of 2008, “Fireproof,” which beat out “Slumdog Millionaire” for the honor. That film focused on a firefighter struggling with his heroic image at the firehouse compared to the image his wife had of him at home. At its heart, it was a movie about saving a marriage. For “Courageous”, the heroes are cops who are courageous on the streets, but need to show that honor begins at home, as they struggle with their roles as fathers when their beat is done.

My role started after principal photography had been completed. Director Alex Kendrick had planned on editing the feature himself, along with the help of on-set editor, Bill Ebel, who was also an editor on “Fireproof.” However, the previous Sherwood Pictures releases had been edited from approximately 40 hours of footage each, but when the final day of shooting on “Courageous” was done, there were over 130 hours of raw footage coming from multiple RED cameras. (The production took place in the spring and summer of 2010, so it was shot Red One, pre-MX.) Getting through 130 hours of footage to deliver a first cut in just a couple months would be impossible for one or two people. Just watching 130 hours of footage would take a month.

My role started after principal photography had been completed. Director Alex Kendrick had planned on editing the feature himself, along with the help of on-set editor, Bill Ebel, who was also an editor on “Fireproof.” However, the previous Sherwood Pictures releases had been edited from approximately 40 hours of footage each, but when the final day of shooting on “Courageous” was done, there were over 130 hours of raw footage coming from multiple RED cameras. (The production took place in the spring and summer of 2010, so it was shot Red One, pre-MX.) Getting through 130 hours of footage to deliver a first cut in just a couple months would be impossible for one or two people. Just watching 130 hours of footage would take a month.

Bill Ebel had done all of the preparation of the material for the edit and had actually cut most of the scenes together while still on set. This was a pretty cutting edge way to work that they’d established on “Fireproof.” One of the people that helped work out this system was post-supervisor, Clarke Gallivan, who’d been brought in on the second Sherwood Pictures release, “Facing The Giants.” With that movie, it had originally been shot to go straight to DVD, but Sony and Provident felt that it would do well in a theatrical release and Gallivan was brought in to supervise the process of preparing the 720p production for the big screen.

With “Fireproof,” however, they shot Varicam, recording directly into a MacPro to the RAID via Final Cut Pro using ProRes 422 HQ. Because they were actually capturing the material live, Ebel was able to actually have completed scenes edited together before they started striking the set in some instances.

On “Courageous” Bill was usually editing scenes together the following day instead of the same day, because the footage was being shot on two or more RED cameras as R3D files which needed to be transcoded via RocketCineX to ProRes 444 2K files before Bill could cut with it.

Bill would get the files from the data wrangler, Stephen Preston. Preston claims to only really be a data wrangler by default. His real job is usually as a sound recordist and mixer, but since his company owned and provided one of the two RED cameras on the shoot, he was “nominated” to deal with the data wrangling.

Bill would get the files from the data wrangler, Stephen Preston. Preston claims to only really be a data wrangler by default. His real job is usually as a sound recordist and mixer, but since his company owned and provided one of the two RED cameras on the shoot, he was “nominated” to deal with the data wrangling.

On “Courageous” the RED cameras recorded to REDdrives, which are basically a couple of laptop 320gig harddrives in a RED branded enclosure, using RAID 0. The drives plugged directly into the camera via a custom cable. They don’t even sell REDdrives anymore but this video on how to use the drive still exists on the internet.

At lunch, but ideally after every scene, Preston would walk from the DIT truck and the first AC would hand him the drive. The RED drive has USB, Firewire 400 and Firewire 800 connections. Preston would link the drive via Firewire 800 to a MacPro tower with two RAID arrays and an LTO drive. He’d copy all the files off the RED drive to one of the RAIDs on the DIT station. Using the R3D data manager software he would make sure that it was copied bit for bit with checksum verification from the RED Drive. Every day after the shoot, all of the footage was backed up manually to the other 16TB RAID 5 RAID and to LTO3 tape, which would be stored off-site.

While the backups were transferring, Preston would take the R3D files through RocketCineX (which is now RedCineX) for a light color correction pass that was usually supervised by second unit D.P., John Erwin. This transcode would create the Apple ProRes 444 HQ files that were used for editing. The transcoded ProRes files would have the exact same names as the R3D files. The R3D files were 4K files. Though some slo-mo might have been 3K or 2K.

The transcoded files would be transferred to a second MacPro with its own RAID via a simple gig-E Ethernet connection. This system was the one Ebel used to start his edit. It was also Bill’s responsibility to sync the ProRes transcodes to the dual-system audio delivered by the sound department. Once Bill had synced the audio to picture, he would leave the original RED guide audio in place, but turn the volume down on those tracks to nothing.

Ebel’s first tasks included all of the footage naming, syncing and organizing. Bill also needed to sync second unit cameras with second unit audio. This was sometimes a RED but sometimes it was multiple Canon 5D Mark IIs with audio from Zoom digital recorders… footage which rarely had slates. Bill also backed up these ancillary 5D and audio files, since they weren’t part of the RED archiving.

Ebel’s first tasks included all of the footage naming, syncing and organizing. Bill also needed to sync second unit cameras with second unit audio. This was sometimes a RED but sometimes it was multiple Canon 5D Mark IIs with audio from Zoom digital recorders… footage which rarely had slates. Bill also backed up these ancillary 5D and audio files, since they weren’t part of the RED archiving.

Once the basic editing chores were done, Ebel would start to cut.

Post Supervisor Gallivan left nothing to chance, running tests of footage and edits up to PostWorks in NY for film-outs and dry-runs on workflow, to make sure that when the production got to the on-line stage, there would be no surprises.

The production began in the summer of 2010, and the production team received mixed feedback about the dangers of changing the original RED file names when bringing the footage into FCP 7 as ProRes. Some said they could, some said they couldn’t. To play it safe, Ebel copied and pasted the original RED camera file names to another column, then renamed the files to the traditional scene and take. Ebel also put all the shots and takes from each scene into its own bin. He also kept several bins of miscellaneous shots that were gathered by the second unit.

The ProRes 444 HQ 2K footage was extremely pristine to edit with. We were often making show reels of various scenes long before the film got to the on-line stage and that ProRes footage always looked great.

Audio was between 2 and 8 channels, depending on the scene. It was all file-based audio recording that was delivered separately, though a guide track was also recorded through the camera itself to the REDdrive.

While a lot of this initial work was more the stuff of an assistant editor, the bonus was that Bill is an actual editor. So when he was done, he would begin cutting, making sure that stuff cut together. Ebel claims that the on-set editing was never really needed, as director Alex Kendrick always had the scene storyboarded in his head. I can tell you from my experience in the editing room later that, with the pace we were going – to deliver the first rough cut in only about ten weeks – it was crucial to have those preliminary edits as the basis for the cut. Many scenes in the final movie are very similar to the way Bill had cut them on set.

While a lot of this initial work was more the stuff of an assistant editor, the bonus was that Bill is an actual editor. So when he was done, he would begin cutting, making sure that stuff cut together. Ebel claims that the on-set editing was never really needed, as director Alex Kendrick always had the scene storyboarded in his head. I can tell you from my experience in the editing room later that, with the pace we were going – to deliver the first rough cut in only about ten weeks – it was crucial to have those preliminary edits as the basis for the cut. Many scenes in the final movie are very similar to the way Bill had cut them on set.

During the shooting day, as time would allow, director Alex Kendrick would break off and see what was coming together in the DIT truck. According to Ebel, his edits were a fun encouragement to everyone, just to see it come together. There were points in the shoot where Ebel was unable to do any editing because the sheer volume of footage was overwhelming, and just keeping up with the basic syncing, naming and organizing chores were all that could be done. If I remember correctly, in the second half of the movie, there were only three or four big scenes that had no first cut to go by.

In the end, renaming the ProRes files in Final Cut was not a problem, the links back to the original R3D files were maintained all the way through the final on-line edit. It was a lot of work that ended up being unnecessary, but Ebel claims that copying and pasting the RED file names to another column didn’t take long and it was worth it for the re-assurance and peace of mind that the original names were there, just in case.

I arrived in August of 2010, settling in to one of the side-by-side Final Cut Pro systems that were set up in a spare room in the basement of Sherwood Baptist Church in Albany, Georgia. Alex and I cut with headphones on, each of us using identical Macs with the same footage on two separate RAIDS.

When I arrived, Alex had already cut about the first 20 or 30 minutes of the movie. The first day, we watched it and discussed my impressions on the cut at that point, before I dove into my first task, which was to make sure all of the “assistant editor” work was really completed for all of the scenes and to cut together “selects” reels for every scene in the rest of the movie. Alex and I used these reels to get a quick feel for all of the footage that we had to work with and refresh ourselves on specific shots, takes and performances. I also annotated all of the takes with my own notes on performances and problems.

When I arrived, Alex had already cut about the first 20 or 30 minutes of the movie. The first day, we watched it and discussed my impressions on the cut at that point, before I dove into my first task, which was to make sure all of the “assistant editor” work was really completed for all of the scenes and to cut together “selects” reels for every scene in the rest of the movie. Alex and I used these reels to get a quick feel for all of the footage that we had to work with and refresh ourselves on specific shots, takes and performances. I also annotated all of the takes with my own notes on performances and problems.

With that done, I started cutting the second half of the movie. Not to give away any “spoiler” information, but my work started at the big turning point in the movie.

The way Alex and I worked was that we would each spend however long we needed to cut a scene. When one of us was done, we’d announce a screening and we’d take off the headsets, and switch our editing system over to play back through the main speakers and on the big-screen monitor that sat at Alex’s end of the edit suite. If I showed a cut, Alex would comment on it, we’d discuss the relative merits and problems and then I’d go back and make the revisions we’d decided on. We did the same thing with Alex’s edits. I’d comment. We’d discuss and then he’d make revisions and have another screening a few minutes, hours or sometimes days later. Each scene was edited on its own short timeline sequence. Each scene’s sequence would reside in the bin with the other raw footage for that scene. At the end of the day, one of my tasks was to take the scene or scenes that I’d cut that day and transfer them via Ethernet to Alex’s system, then I would have to relink the sequence to the media on Alex’s RAID. With that done, I would edit my footage to the end of a master sequence that included every scene in the movie. While we were editing individual scenes, we always just worked on a sequence with JUST that scene, but Alex was also working on a sequence of the entire movie that ended up being two and a half hours long! We never really broke it into reels until the on-line process at PostWorks.

About a month before we needed to deliver the first draft to the executives at Sony/Provident/TriStar we had a pretty good idea that we were running quite long. If you’ve ever heard or read the “inside scoop” on editing a feature, this is nothing unusual. Most movies have a very long first cut, compared to the length that they’re eventually released. Some movies, famously, need to almost be cut in half from their original edit. Our case wasn’t that bad. The folks at Provident had laid down a pretty firm rule that the movie could not be longer than 2 hours. The Kendrick brothers and Sherwood Pictures have tremendous creative control, but the length of the movie was something that they knew they really needed to hit in order to have a chance for the movie to succeed financially.

About a month before we needed to deliver the first draft to the executives at Sony/Provident/TriStar we had a pretty good idea that we were running quite long. If you’ve ever heard or read the “inside scoop” on editing a feature, this is nothing unusual. Most movies have a very long first cut, compared to the length that they’re eventually released. Some movies, famously, need to almost be cut in half from their original edit. Our case wasn’t that bad. The folks at Provident had laid down a pretty firm rule that the movie could not be longer than 2 hours. The Kendrick brothers and Sherwood Pictures have tremendous creative control, but the length of the movie was something that they knew they really needed to hit in order to have a chance for the movie to succeed financially.

The first cut that we delivered didn’t have to conform to any time limit, but Alex and I were having pretty constant discussions while watching every scene that often centered around how much of a scene was really necessary. Could we cut out the first 15 seconds? Could we cut out the last 15 seconds? Did we really need this bit of character development or was that joke really necessary? We knew we were going to have to make some pretty difficult cuts later in the process, so the more we trimmed as we went, the easier it would be to fix later on.

My job on the production was to help get Alex to the first cut that needed to be shown to the distribution executives at Sony and Provident on October 1st of 2010. Once we made that deadline – in the nick of time – my work was over.

When I left Albany, we had a really nice movie. We knew it was too long at two and a half hours, but we also knew that it was really impactful and that cutting it down to two hours would simply serve to distill the essence of the movie and make it more powerful by tightening it up throughout. All of those decisions – cutting 20% of the movie that Alex had lovingly co-written and directed – were hard decisions. Some were deeper than he wanted, I know. I know that one of the scenes I worked hard on – a lengthy weapons training scene that provided some good diversion and an energy boost at a certain spot in the movie – was cut out entirely.

When I left Albany, we had a really nice movie. We knew it was too long at two and a half hours, but we also knew that it was really impactful and that cutting it down to two hours would simply serve to distill the essence of the movie and make it more powerful by tightening it up throughout. All of those decisions – cutting 20% of the movie that Alex had lovingly co-written and directed – were hard decisions. Some were deeper than he wanted, I know. I know that one of the scenes I worked hard on – a lengthy weapons training scene that provided some good diversion and an energy boost at a certain spot in the movie – was cut out entirely.

In the next installment of this article, I’ll discuss the on-line process that took place at PostWorks NY. That article will explain how the Final Cut Pro sequence was conformed back to the R3D files from the RED camera and how it all got color corrected and delivered to the big screen.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now