I love a challenge, as that’s when I get to do my best work. One of these spots was easy, one was moderately difficult, and one was hard. All turned out perfectly.

Before I go any further, take a look at the finished pieces:

Each of these three spots has a name. In order, they are: “Lightbulbs,” “Napkins” and “Typewriter.”

Texture makes a difference. Our brains love variety. I often use dappled lighting to break up flat, even surfaces. Textures built into the set allow me to light more simply and quickly.

Based on the boards, this spot looked easy to light. The camera move could be executed on a dolly.

This prompted me to call my line producer, Christopher Knox, and ask for a Technocrane.

“Hmmm,” he said. “Can you do this with a jib instead? We’re not really budgeted for a Technocrane.”

“Maybe,” I said. “The jib operator is going to have to jockey the base around a bit, as the arm pivots in space as it swings up. If they say they can boom up while pushing the crane across the floor to maintain the composition, I’m happy to use a jib.”

“Okay, let me call the crane guy,” he said. About an hour later he called me back. “We’re using a Technocrane.”

As a compromise, I offered to shoot the project on a classic Arri Alexa. That camera is about six years old now but looks as phenomenal as an Amira or Mini. The disadvantage is it won’t shoot resolutions higher than HD. The good news is that it’s a lot cheaper than an Amira or a Mini.

Shuffling money around to make the project work is a key part of commercial production in the modern world, and while I certainly love to work with the latest and greatest tools, I also know exactly what kind of camera gear I can get away with for any given job. Shooting green screen with a Canon C300 is a disastrous mistake. Putting a heavy zoom on a Sony FS7 will result in soft focus post-production tears. A RED camera captures critical color with one particular OLPF filter, and one only. Things were easier in the film days. Now… it helps to be a serious geek when figuring all this out.

Fortunately, I am a world-class geek.

Often I’m able to give production choices: “I know you want to use camera “X,” but I can give you a comparable look using camera “Y” so you can put the savings into something else that we need to make the job a success…” Like a Technocrane.

For my part, I told Knox that I would use the Technocrane for every setup, as it’s much faster to use than a traditional dolly. There’s a lengthy camera move in each of these spots, so a Technocrane could really pay off for all three. We only needed it for one shot, but it was going to reduce setup times on every shot.

I could have shot this last spot using a dolly, but the end of the Technocrane is very narrow (the camera is wider than the arm) and the crane eliminated the need for dolly track. As we’d be shooting lots of reflective glass very near to the lens, moving the camera on a narrow black arm made more sense than on a large shiny dolly mounted on track. If we hadn’t needed the crane for “Napkins” I’d have made a dolly work, likely by draping it, myself and the dolly grip in black duvetine. That’s not my favorite way to work, but it would have been a cost effective choice.

“Lightbulbs” was clearly the hardest setup from a rigging perspective, as we had to hang dozens of lightbulbs in an attractive cloud formation. I outlined the following specs:

- Each bulb must be easily and quickly adjustable, both in height and location.

- Each bulb required its own dimmer.

- The bulbs in the center of the rig had to be built on an adjustable channel system. I wanted the camera to just barely clear them as it pulled back, so the nearest bulbs swept dramatically past the lens.

This sounds simple. In reality it required a small truss setup with a hundred pounds or more of cabling, no floor stands, and a portable 30-channel dimmer system.

STAGING THE SETS FOR EFFICIENCY

Originally, when I spoke to art director Bret Lama about how to arrange the sets on the smallish stage we had to work in (such are the realities of living in a secondary market), we spoke of putting them side-by-side. After doing some measuring, though, I suggested stacking them up in a line.

The crane specs showed that its collapsed length was about 14′. That left 28′ in which to build the set and move the camera, which was *probably* enough, but I dislike working at the limits of what I have available. I knew I wanted to use a large light source to reveal the lightbulbs’ reflective glass surfaces, and it occurred to me that rotating the set 90° away from the stage’s white cove would allow me to turn that cove into a bounce source.

Further, as the “Lightbulbs” and “Typewriter” sets consisted of single walls, we could build them parallel to each other and dress both at the same time on the pre-light day. Upon finishing photography on the first set we’d take that wall away to reveal the next wall, move in a new desk and props, make a couple of lighting tweaks and be ready to shoot without having to shift the crane base.

This arrangement worked for a number of reasons. We could set up the Technocrane operating station at the beginning of the day and never move it again. The crane itself only had to move once, to get to the “Napkins” set. We used the same shooting space and overhead rigging for our two single-wall sets. And the first two sets could share some lighting while giving us room to pre-light the third set.

“LIGHTBULBS”

Knox and I had a discussion very early on about the “Lightbulbs” set. We’d already planned to rig most of the lighting, with full grip and electric crews, on the day before the shoot, but the art department had an additional day of set construction. He put some money aside so my gaffer and I could come in on that first day and work out the mechanics of the cloud rig without our minions standing idle. (We overachieved: by the end of the day we had all three sets figured out, and “Napkins” was 75% pre-lit!)

We settled on a speed rail truss system that we’d build on the floor, supported initially by floor stands. Once the rig was built, the grip crew would run speed rail down from the grid, grab the truss, and pull the floor stands away.

I wanted the lightbulbs to pass as close to the camera as possible, so I asked that the middle bulbs be rigged from two movable pipes. This gave us the ability to quickly set a channel width for the middle rows of lightbulbs.

We ran out of speed rail, so we had to improvise with wooden boards. To the left of the board there are two pieces of pipe that run parallel to each other. (You can see the ends sticking off the back end of the rig, and the clamps that hold them in place.) Those are the channel pipes. Once the camera was in place we were able to change the width of those pipes such that the camera passed as close to those bulbs as possible over its move.

I told my gaffer, Andy Olson, to bring every stinger he had. He laughed. The next day, during the pre-light, he told me, “I thought you were joking, but I brought them all anyway. We’re using almost all of them!”

The “channel” pipes are easily visible here as they form a “V” that extends across the length of the truss. All lights are hung using A-clips, for speedy adjustment.

Andy brought a 30-channel dimming system, and we rigged 32 lights in total. (Four lights shared two circuits, but we put those at the end of the move and assumed the audience would never notice them coming on simultaneously amongst all the other cloud lights.)

As far as lighting the set, I’d initially wanted to use soft side light to create broad linear highlights in the bulb surfaces. One of the reasons I’d asked the sets to be oriented at a right angle to one of the stage’s white cyc walls was so I could use it as a large bounce source. My key grip, Gordon McIver, went even further and turned it into a massive book light.

The light source to the right was three Arri M18s aimed into a cyc wall, which was then further diffused by a frame of 12’x12′ grid cloth. The reflection of this source on one lightbulb was pretty, but seeing it on 30 lightbulbs was amazing.

The big light source was the easy part. It took the better part of a day to rig and power our “truss o’ bulbs.” Once we had everything roughed in, I snapped some photos and texted them to Greg Rowan, our director, who then talked me in on the overall shape of the bulb cloud. We were 95% ready at call time the next day, with only some final bulb adjustments once the camera was in place. Every light was held in place by a spring clip on its cord, so changing the height of each bulb was easy. Adjusting the placement was a little more difficult as we could only slide the bulbs left, right, forward or back on the bar to which they were attached, but we made do by adding crossbars, and then crossbars between crossbars.

Unfortunately, on the shoot day, the big soft source lighting scheme had to be scrapped as it revealed seams in the set walls that the client didn’t want to see. The seams in non-textured flats can be hidden by taping them over and painting them, but this doesn’t work on textured flats. I’d hoped that the seams could be explained away as possible grout lines in a brick facade, but early that morning some concerns were expressed and I initiated a backup plan. Once the final decision was made to hide the seams, we switched off the big source and turned on some smaller ones.

A Source 4 Leko, hung from the end of the truss, lights up the desk blotter, creating a soft bounce source. A 4’x4 Kino Flo peaks over the back of the set as a backlight. We later added a splash of light from a tweenie on the back wall to bring out its texture and prevent it from fading into blackness.

The bulbs lit themselves, but I needed a quick and elegant way to light the actress. I find low bounced light sources to be especially interesting as they feel “ambient” to me, as if they naturally belong no matter the environment. Sunlight striking a floor creates much the same look, and indeed there are many situations where much of the light in an environment is light radiating upwards from flat surfaces. I had the electrical crew hang a Source 4 from the truss and aim it at the desk blotter, which was a large enough source to wrap nicely around the actress’s face.

Alexa’s wonderful dynamic range and highlight handling allowed me to do this without worrying that the blotter would blow out to an awful, clipped video white. It truly lets me light as I would when shooting film.

The original Stanford University Shopping Center Apple Store design incorporated huge, milky plexiglass ceilings lit from behind by fluorescents that made the ceiling a single large, flat and perfectly diffuse light source. The floor was made of a very bright white material that caught this light and reflected it upward, resulting in nearly equal amounts of light from both the floor and the ceiling. The store interior felt as if it had an internal glow, and everyone inside was lit as if they were a fashion model. Sadly, the floor scuffed easily and was eventually removed, and while the ceiling is much the same, the feel of the store is very different without the radiant white floor.

When in doubt, I’ll often light from below. I started doing this in my low budget corporate video years, when I frequently found myself lighting people at conference tables. The most interesting—and quickest—solution was to hang a light overhead and smack it into the table, where scattered pieces of note paper bounced the light back on faces. I was able to shoot in any direction, and the soft upward shadows felt both interesting and real.

We scheduled “Lightbulbs” first as Knox and I decided to get the hardest setup out of the way early in the day. Although Andy and I tried to create a preplanned bulb illumination sequence, fading up specific bulbs as they entered the frame, this proved too time consuming. In the end we gave Andy his own reference monitor near the dimmer board and let him feel his way through the shot.

We set an overall bulb brightness level on the dimmer board using the master fader, so he could focus on bringing the individual faders up at the proper times without having to hit the same brightness level 30 times.

The foreground was very warm, so I lit the background to be a little cool. Cinematography is about creating depth and contrast, and it’s well known in design circles that “warm colors advance and cool colors recede.” Making the background a little cool created a pleasant color contrast between foreground and background while enhancing the depth of what is a not-very-deep shot.

One thing I love about the Technocrane is that I get to operate wheels again. I miss gear heads. They’re so smooth, precise, and just plain fun.

It’s clear that I’m doing some operating at the beginning of this camera move, but once I’d finished tilting up I had to immediately start tilting down to keep the top of the frame level across the rest of the move. The fact that I’m spinning wheels throughout this shot is impossible to see in the final spot, but it would have been obvious if I hadn’t. I love that.

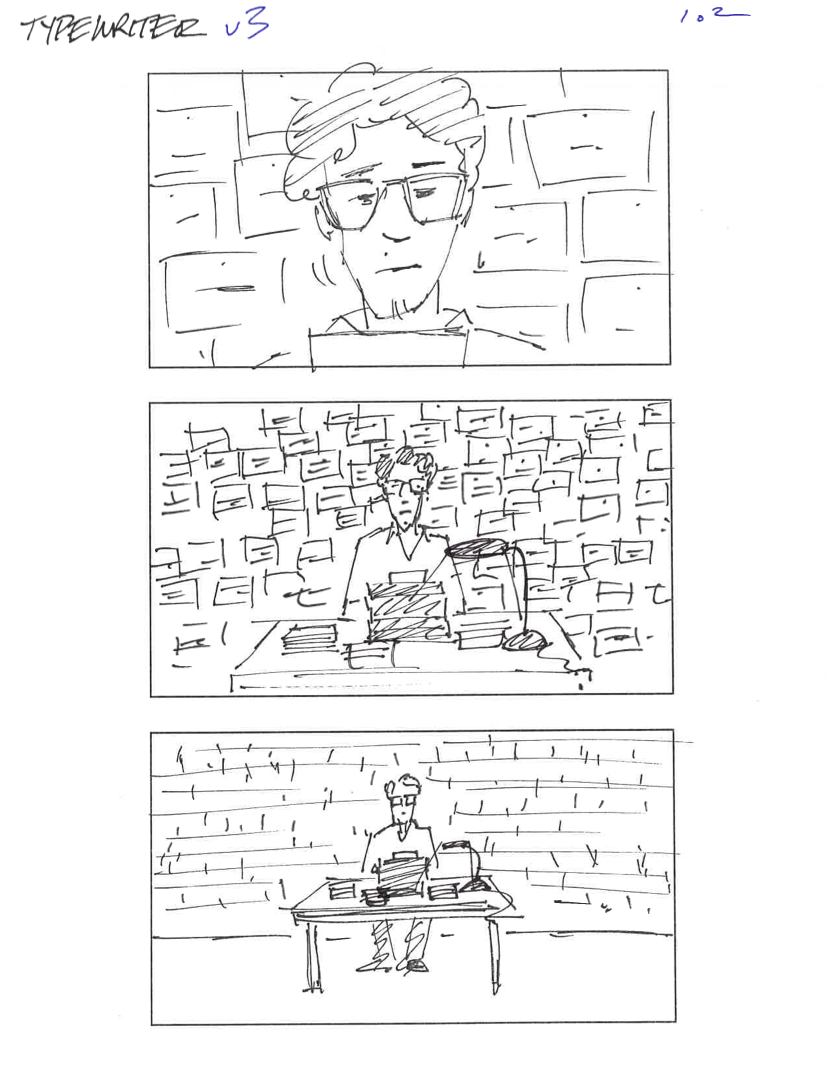

The same thing happened on “Typewriter.” The crane arm wasn’t perfectly dead on to the set, but I was easily able to keep the actor perfectly centered across the entire move. The camera doesn’t appear to be panning or tilting at all.

“TYPEWRITER”

Once we had “Lightbulbs” in the digital can, we swapped out the desk, knocked down the set wall, and quickly lit for “Typewriter.” We’d already rigged two 4’x2 Kino Flos on the “Typewriter” set wall to act as large, downward washes. We’d left the large soft source for “Lightbulbs” built and ready to go, so we turned it back on for ambient fill. We also taped a piece of typing paper to the keys of the typewriter and aimed our Source 4 at it for a little upward-facing glow.

This small bounce wasn’t a big enough source to be flattering to the actor’s face on its own. We added a small Chimera, fitted with a directional grid and rigged to our overhead truss system.

In order to speed things up, we didn’t bother removing the light bulb rig until we’d finished this setup. I had the electrical crew pull all the lightbulbs up to the truss, and we waited to disassemble it until we moved to the final “Napkins” setup.

I would have preferred to light this with the table lamp only, but that would have required cutting the shade and using a bigger bulb. Art direction decisions of this type often happen on the day of the shoot, and I opted not to spend time tearing apart a lamp on a moment’s notice. Half of my job is getting the look right, and the other half is getting it done on time.

There’s not much else to say about this spot. It was very straightforward. The Technocrane worked perfectly and the lighting setup was fairly simple. While shooting this setup I had the electrical crew work ahead and turn on the lighting for the “Napkins” spot, which we’d already put in place.

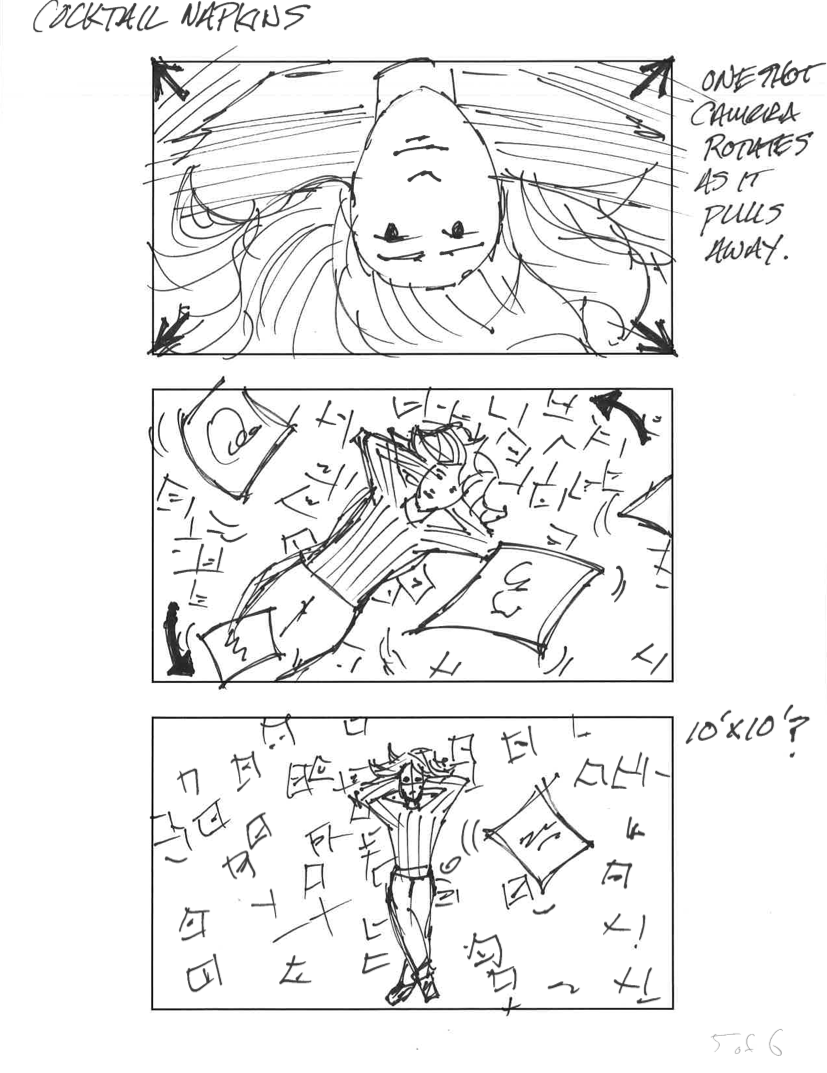

“NAPKINS”

Initially this setup was a bit of a quandary. I knew I had to light someone laying on the ground and then pull straight back for a good distance without seeing lights or casting camera shadows. I had a full set of Cooke S4 primes on set, but I’d decided to only use the 32mm when possible. The 32mm is wide enough to capture a good-sized set in a small space, but isn’t so wide that it distorts faces in unpleasant ways. As all three spots started in closeup and ended wide, the 32mm seemed like the best choice for each setup. (32mm and 35mm primes are great all-around lenses. If I’m handheld and shooting quickly, I’ll often put one of those on and never take it off.) In theory I could’ve only rented the 32mm lens, but that’s asking for trouble if anything changed at all on the day of the shoot.

The trick in preproduction was to figure out whether I could get a head-to-toe shot on a 32mm lens at our maximum camera height, which was 18′ to the stage’s grid. I also had to find out what my angle of view was at that height, so I could tell the art department how much floor space to dress with napkins. It’s times like these that PCam is invaluable. Thanks to its various calculators I determined that it was possible for me to get a head-to-toe shot on a 32mm lens at 18′, and also that I needed 12’x12′ of “napkin space” to fill the final frame.

During our “pre pre-light” day, Andy and I talked about ways to make this sea of napkins interesting while also lighting an actress’s closeup. I’d toyed with bouncing light off the cyc wall, but it felt like that might be too broad for what was essentially a person laying on a flat white surface. Even confining the bounce to the lower part of the wall, such that it skimmed the napkins, seemed like it might be too much of a flat wash, and it left the issue of getting light around the front of the actress’s face from a very high angle. I broached the subject of hanging a Chimera in the grid, but Andy talked me out of it as he hates hanging lights in case he has to move them quickly. The napkin floor would have kept us from bringing in a ladder or a scissor lift unless the light was hung well off center.

In the end I embraced my “inner hard light.” We put a 2K fresnel on a stand as high as we could get it, and the angle turned out to be perfect for a classic, 1950s Hollywood key light. One of the tricks with hard light is getting the fill light right, as hard light casts shadows that emphasize skin imperfections. Lowering the contrast of those shadows, by placing a soft light near the lens—and preferably under it, so it reaches into the actor’s eyes—fixes a lot of issues. We had a small portable LED light ready to mount under the lens in the event I needed it, but the actress had perfect skin. She was a dream to light.

I wanted to create a pool of light around the actress, but not in a perfect circle as if it were a spot light. As part of our “pre pre-light,” Andy and I experimented with distorting our key light in interesting and visually random ways. We started off spotting the light all the way in, to create a pool of light with a hot center that grew darker at the edges. Then we added a cucaloris (“cookie”) for some breakup. Normally you’d flood a light all the way out so the cookie cast hard shadows, but I wanted to see how the shadows softened at full spot.

And… it was too soft. The pattern was mush.

I knew from experience, though, that adding another pattern would cause the two patterns to interact, so I asked Andy for a second cookie. He didn’t have one (almost no one carries them anymore, they’re considered a bit dated) but he had a piece of foam core with a round hole cut in it. We set that inches in front of the spotted fresnel to see what happened.

It was magic. The result is a little hard to see in the final shot, but the interaction of the small aperture in the foam core, the spotted fresnel, and the cookie resulted in a wonderfully random pool of light. It looked amazing on the Sony A170 OLED monitor we used on set, although it loses a little something in a highly compressed 8-bit file. Still, it looks fairly nice: not too theatrical, not too perfect.

This is a trick I use often. Stacking patterns causes the holes in the front pattern to act as apertures through which the rear pattern is projected. The result is a wonderfully random combination of hard and soft shadows that interact in unpredictable ways. I wrote an article about this effect here.

At each corner of the napkin region we placed a 4’x8′ piece of foam core, and bounced a Kino Flo into each one. Ideally I’d have filled from behind the camera, but no matter how big the source I’d still end up shadowing the actress with the camera at the beginning of the shot. Placing large bounces around the perimeter of the shot gave me the same effect without putting any lights behind the camera.

We placed four Source 4 Lekos on the ground, two on either side of the napkin field, to skim across the napkin edges and prevent them from appearing too flat.

We may have added a light CTO gel to the 2K fresnel to make it feel a bit like warm sunshine.

All that was left was to finesse the camera move. The crane operator, Robert Barcelona, placed the camera in a direct-down position on the head, and then joined me in operating it. My job was simply to pan, while he retracted the arm over the course of the shot so that the camera started centered on the actress’s face and ended up centered on her body.

This pool of light doesn’t look like it took a lot of work to create, but natural light can be surprisingly hard to reproduce at times—because it’s never perfect.

It took a couple of rehearsals to choreograph our dance, but we figured it out fairly quickly. Robert had the hardest job, as precisely retracting the arm while watching a spinning image couldn’t have been easy.

Alexa presets tend to look a little green. Adding CC-4 to the color temperature (top right, “3200 -4”) tends to fix this issue. I use a center “dot” instead of crosshairs when working with Alexa, as I like to see the center of the frame without showing the director and clients a crosshair. (One of my assistants likes to make the frame lines and crosshair red, to emulate the old “Panaglow” illuminated markings that helped film operators frame shots at night. Red worked well in that case because it didn’t affect night vision, but I prefer white because—in every other context—red indicates an error.)

TECHNICAL SPECS

We shot this on an Arri Alexa Classic, and while the savings in rental price over an Amira or Mini didn’t buy the Technocrane, it certainly defrayed the cost somewhat.

For quite a long time I’ve been very picky about noise, and I will normally rate a camera at half its stated ISO as most aren’t as noise free as I’d like. I’m starting to ease up on that practice, but at the time I shot this I was still deep in my anti-noise phase, so I rated the camera at ISO 400. Reducing noise does help in compression for the web, which is where a lot of my recent projects have landed.

I’d wanted to shoot the project on TLS-rehoused Cooke Speed Panchros, which are beautiful old lenses with all sorts of funky anomalies. Sadly, my assistant found that the 32mm was out of collimation at the prep and there was no one in the rental house on the prep day to fix it. I ended up with a set of Cooke S4s, and I really can’t complain as those are phenomenal lenses for shooting closeups, but the funkiness of the TLS Cooke Speed Panchros would have added an extra something to the project. The bokeh on “Lightbulbs” would have been wonderfully random, and the natural vignetting in those lenses would have added some character to the fairly flat fields of both “Typewriter” and “Napkins.”

“Lightbulbs” and “Napkins” were shot at T2 as I wanted the backgrounds to go a bit soft, at least at the beginning of the camera move. “Napkins” was shot at T4 1/2 as reduced depth of field didn’t make any difference to the flat set, and I decided to give my camera assistant—the excellent John Gazdik—a break at the end of the day. He didn’t need it, but I remember my days as a camera assistant and I try to be kind to mine whenever possible.

I nearly always shoot with a 144° shutter (1/60th second exposure at 23.98fps) as I’m extremely paranoid about flicker. Fluorescents flicker, LEDs flicker, and recently I’ve even seen tungsten halogen bulbs flicker.

My theory is that energy efficient halogen filaments are thinner, so they cool—and dim—faster when the AC current changes directions. I’ve had issues when shooting on-set tungsten practicals at 48fps/180°, and I’ve seen the same practicals flicker at 24fps/180° when dimmed. 144° puts me directly in the middle of the 60hz flicker-free window, and allows me to worry about more important things than whether an errant lightbulb might be misbehaving in the background… or, in this case, 30 dimmed lightbulbs in the foreground.

All spots were shot at 23.98fps to LogC, ProRes4444.

Production Company: Teak SF

Director: Greg Rowan

Line Producer: Christopher Knox

Executive Producer: Greg Martinez

Director of Photography: Art Adams

Art Director: Bret Lama

Gaffer: Andy Olson

Key Grip: Gordon McIver

First Camera Assistant: John Gazdik

Crane Owner/Operator: Robert Barcelona