In this week's “Answers Occasionally Given,” I tackle a question about efficient scene balancing workflow; whether it's better to apply stylistic adjustments as part of one's initial grade, or separately. Then, I discuss another reader's strategy for identifying color imbalances, and how it intersects with the use of automated tools for color balancing.

As always, I'm only as interesting as the questions you send me. If you have a question about color theory or technique, grading workflow, creative corrections, or any interesting intersection of production and post, feel free to send it to ask@www.provideocoalition.com

Jamie Dickinson asks:

In his webinar, Pat Inhofer suggested balancing/matching shots and then afterwards adding the “look,” which applies with less tweaking if the shots are balanced already. How long can you spend going through a film/scene just matching the shots with a neutral grade before going back through it all to add the “Look?” I tend to just apply the grade, perhaps with the 'Look' within a separate layer/node(s), all in one go and just put up with tweaking it as I go. What are your thoughts?

Pat suggests a very professional workflow that offers a lot of flexibility when the client decides to change their minds five times when you’re supposed to be outputting to deliver to broadcast. By balancing clips neutrally in a first pass and then applying a stylistic adjustment on top of that using whatever grouping or adjustment layer mechanism your software provides, changing up your stylistic grade can be a snap. They don’t like the hard blue undertones they asked for on Monday? Fine, adjust a single grade to change the entire scene to a pale blue wash with protected dark shadows instead, with no need to readjust every single shot.

However, it’s been my experience that this two-pass approach is more time-consuming then simply doing match-and-style with one grade, and can be unrealistic for projects with parsimonious budgets. This is especially true if the client’s definition of a “look” is for a touch more warmth in the highlights, or a bit more blue in the midtones, which could arguably be simply a different way of balancing the scene, easily accomplished as a slight continuation of your adjustment in the primary grade.

In fact, the difference between a neutral grade and a “style” grade for something like a documentary project, where the client doesn’t want anything too exotic, can be subtle to the point of invisibility, depending on who’s calling the shots. In this case, doing everything in your main grade is a simple convenience.

The bottom line, for me, is one of time. If you’re working on a well-budgeted program and your client’s initial availability is limited, you can take advantage of down time by preemptively balancing each scene in advance. Once the client rolls in, you can work with them to apply stylization to the whole scene, and modify the look two or three as necessary to get the client’s buy-in. When following this approach, keep in mind that shots that seemed perfectly balanced with a neutral grade might go out of balance once you start pushing the contrast or the color balance in a different direction, so even when you’ve pre-graded, you may still need to continue tweaking the odd shot for balance.

Another thing to consider is that grading workflows are not always either/or. If the main look the client is going for is a subtly warm, slightly higher contrast treatment that you’ve decided to simply build into the primary grade, then doing an all-in-one grade makes a lot of sense. However, when the client comes back and changes their mind, wanting to cool the overall look down and lift the bottom blacks up, it’s perfectly acceptable to add this adjustment on top of what you did previously so long as you didn’t clip or overcompress valuable image detail in the initial grade. If you did, then you’ll need to either go back and change your primary adjustments to accommodate the new look, or apply the modification as a layer or node before your primary adjustment.

Rubén Abruña asks:

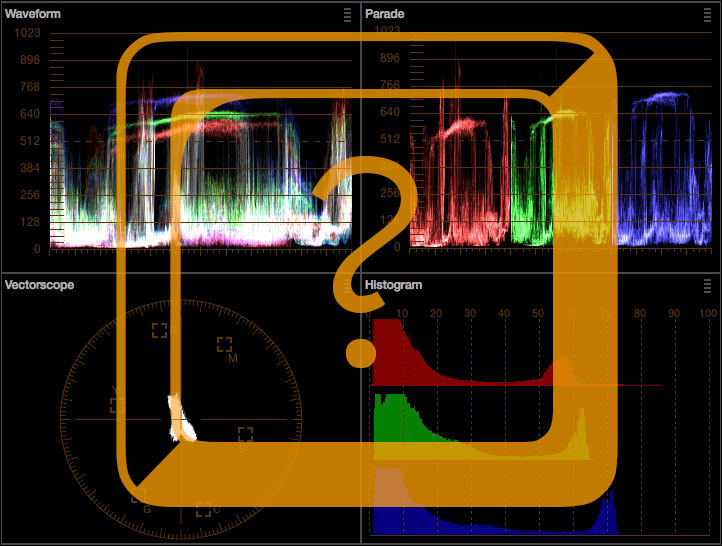

From my Avid color grading experience, I regularly use the eye dropper to sample portions of the image to get an idea if there is a color cast. I am finding myself using the same technique in DaVinci Resolve 9 and it has proven very useful. Of course my monitor, my scopes, and my eyes are also important parts of the grading process. But what do you think of this technique?

I'm assuming by “using the eyedropper” what you're doing is sampling an area of the picture that's supposed to be either white, black, or neutral gray, to find out how much of an offset there is between the R, G, and B channels (an offset indicating a color imbalance), and making either an automated or manual adjustment to neutralize the zone of image tonality affecting that area of the picture. This certainly can be an effective technique, so long as you bear in mind that subtle variations in the picture (such as noise or grain) may yield differing analyses from pixel to pixel. This can be especially true for applications with automated shot matching, where clicking on two different areas of the same feature can give you significantly different results.

You also need to bear in mind that some of the color imbalance in a scene might actually be attractive, so that achieving a totally neutral adjustment is often not really desirable. Of course, that's both a matter of taste and of the needs of your program.

Which leads me to some observations about automatic color grading tools, which typically use the same technique of sampling shadows and highlights to determine what, if any color cast there is, automatically rebalancing the RGB color channels to neutralize it. There's absolutely nothing wrong with using automated correction tools, if and when they give you what you want.

The main issue I have with automated tools is that, more often then not, I find them hit-and-miss to the point where it's just easier for me to make the base correction I’m going for myself, and I simply forget to use them after a while. Also, I find that sometimes the corrections they make are more extreme then I want, either radically overcompensating, or neutralizing all of the soul out of the original image so that I have to partially undo the fix to restore some of the original character of the shot that I liked.

However, every once in a while when I’ve got a shot that just bedevils me, I’ll try the available auto-fix, and if it works I keep it. It's always worth a try, and you can always undo.