You’ve spent months editing and grading and finishing your beloved video. But now you have to upload it to social media for it to be seen by the world and you want the best quality possible. I thought I’d take a look behind the scenes of YouTube’s encoding and how to get the most out of it.

I am old enough that some of my early work can be found on YouTube at very low resolutions. This music video I cut with Pete Doherty wandering around London was shot on 35mm black and white film stock and is on YouTube at a miserly 360p. It makes me want to cry.

With YouTube supporting 4K and 8K and even HDR, you want the best quality you can when you upload and you want to minimize the degradation that YouTube’s encoding does to your video.

Recommended Specs

YouTube’s recommended specs page is written with the average user in mind and can be safely ignored. There’s no mention of uploading ProRes (or Cineform or DNxHR for that matter) and yet you can and you should if you have the bandwidth, especially as YouTube, unlike Vimeo, has no upload quota. Doing this avoids one extra round of H.264 encoding. Many people have tested and shown that YouTube will re-encode what you give it no matter what (one even testing what happens when you run it through YouTube 1000 times!). So that does away with trying your best to make the best low bitrate H.264 encode you can.

Clearly, with the volume of video that passes through YouTube (estimated at around 300-500 hours every minute!), they can’t spend the quality time encoding our masterpiece as we would like and they have to keep the bitrates right down. A general rule for encoding is that you get better quality video if the software encoder takes longer (e.g. 2 pass encoding in Premiere or the slow preset in Handbrake) or if you keep the bitrate higher. Youtube isn’t keen on either of these options as it has so much video to encode that it wants to get the job done quickly and lowering the bitrate means less server storage space & a lower demand on the viewer’s internet connection. It also has to make multiple files so that it can dynamically switch resolution on the fly.

That said, it has improved vastly over the years as can be seen from my old video from 2009 and it is possible to look behind the curtain and see what files YouTube is making, for example with the command line tool youtube-dl.

Behind the curtain

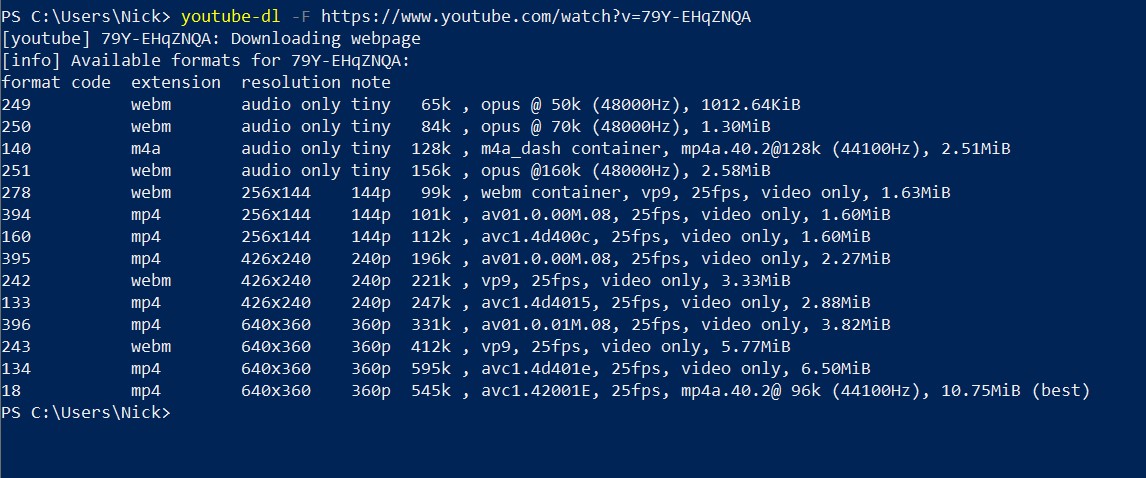

Here is the output from youtube-dl on my old video using the -F flag to see the files available:

It shows that there are 14 different files even with a maximum resolution of 360p.

The columns are in order:

- Format code – a number that you can target if you want to download that file

- File extension – represents the container (the packaging around the codec) which we won’t worry much about here

- Video Resolution (written as both 640×360 and 360p which are the same thing)

- Bitrate

- Codec, frame rate, file size, etc.

You can find HDR YouTube clips with over 40 different files associated with the video like this one which gives this output:

This might seem overly complicated, but there are a few key conclusions we can draw which will help us.

You can see that YouTube encodes using three different video codecs:

- H.264 a.k.a AVC

- VP9, which is pretty similar to H.265 a.k.a HEVC, but avoids the licensing. It takes longer to encode, but the file size is smaller (see this frame.io blog for more info)

- AV1, which is VP’s successor.

Each is a new generation of codec which can get the same quality at a smaller file size, which is great for YouTube. The trade-off is that they in turn take longer to encode and this is why your YouTube upload initially might only show in SD and then HD and can take a long time to show in 4K (sometimes it’s the next day). They also require more powerful hardware to decode – which is why you often see editors complaining about the H.265 files they’ve been sent – but in this case, it means your device will decide what you see. You have some control in your YouTube playback settings but I doubt many people are changing those, plus YouTube is going to make sure you can watch the video before any quality concerns. The takeaway is that the quality the viewer sees is variable and depends on both their internet connection and their hardware.

A question that comes up a lot is this:

Should one upload to Youtube in 4K?

Seems like a no-brainer if your file is 4K, but what if you only have an HD video?

Testing

I ran some tests to see how YouTube would handle both a 1080p file and an upscaled 4K UHD file of the same clip.

I found:

- For the H.264, the difference was minimal

- For the VP9, the file created from the 4K upload was much better

- The VP9 files had a slightly better sharpness but had a colour shift (this is an ungraded clip and it may be that the colours are out of gamut)

This is just a snapshot test so I would encourage you to test your own footage (testing a 10-second reference export saves time).

YouTube favours 4K

The youtube-dl info shows that the 4K UHD VP9 file was 8Mbps compared to the 1080p file being 1 Mbps. Granted a 4K UHD video is like 4 HD videos stacked together, but then you’d only expect four times the bitrate, whereas it’s 8 times higher. YouTube clearly favours 4K (but as I said above, you have to be pretty patient before this actually shows up).

My conclusion is that there are major advantages to uploading 4K video to YouTube. Even if you are working in HD, you might find it’s worth your time to upscale it before uploading, especially if done at high quality (see our recent upscale shootout link: A.I. Upscaling Software Shootout). There is also a measure of future proofing to this – YouTube’s 4K encodes are currently better quality and more and more people will watch it in 4K moving forward.

The caveat to this is that doing the upscaling might mean introducing digital-looking artifacts or over-sharpening and this might offset any gains you might have. Either way, those of you who gaze at your grade 1 monitor for a living may be better not to see it on YouTube at all.