By the end of World War II, motion pictures were coming to the end of their Golden Age. In three different surveys, 1956 movie attendance was down almost 50 percent from its peak in 1946. Television has been blamed but statistics cite multiple reasons as the cause of the sudden drop in ticket sales. Some are related to television and others are separate issues.

Urban sprawl (the growth of the suburbs) and expanding families only added to the studio’s problems being dealt with at the time. There was also the Blacklist, Supreme Court decisions regarding ownership of TV stations and theaters and the abolishment of the studio system. Families were electing to stay home and watch a tiny flickering image coming into their homes for free. As televisions continued to go from furniture store showrooms to home living rooms by the thousands, Hollywood realized they had to find something to make movies stand out from their nineteen inch screen competition.

So what could they control? How could they beat this new technology? What would lure people out of their homes into a theater?

Interestingly, reading through the materials preparing this article, it seems all the technologies had already been designed and built in some way shape or form. Beginning in the early fifties, the film studios tried to find ways to gain back some of its audience using “new” technologies. Some of the methods had been around since the teens and the twenties. But with the new sense of urgency, inventions the studios had previously ignored now became viable.

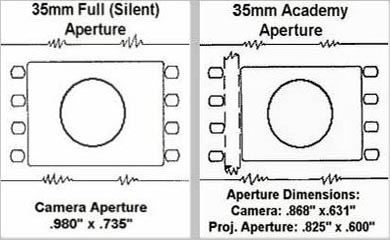

Thirty-five millimeter (35mm) had been around since the late 1800’s. But eventually, in 1907, the motion picture industry standardized 35mm by international agreement as the professional film gauge. It was also agreed upon that the filmstrip was to be vertically photographed and projected, that each frame was to be four perforations high on both sides and that the projected image should have an aspect ratio (the width of the screen divided by the height) of 1.33:1. This ratio was recognized by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and became known as the Academy Standard. However, as sound came in the Academy Aperture was adjusted to 1.37:1 to allow space for the optical sound track while remaining very close to the original 1.33:1 silent screen shape. In remained unchanged until the 1950’s.

When the National Television Standards Committee developed its standard for black & white television in 1941, it was decided to carry the same 1.33:1 ratio over to television and broadcasting in the United States.

As the second half of the twentieth century began, Hollywood was treating the movie going public to films that were bigger than they had previously experienced and had more “gimmicks” associated with them. “The film industry had three major campaigns involving technical advances with wide-screen experiences, color and scope,” as referenced by Tim Dirks in AMC’s filmsite.org. These were: Cinerama, 3-D and Smell-O-Vision and CinemaScope. Let’s take a look.

The biggest (and longest lasting) of these were the wide screen presentations. The screen grew from its 1.37:1 ratio to several widths depending on the studio or production company that was releasing the production.

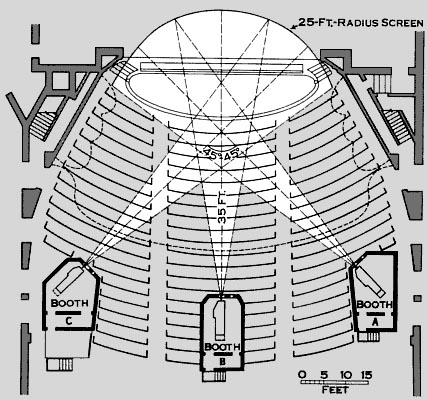

The first release of a three camera process was “This is Cinerama.” It was a travelogue designed to keep audiences glued to their seats as they experience a roller coaster ride, a flyover of Niagara Falls and water skiing show from Cypress Gardens. Since it required three complete projection booths and space for a seven-track surround sound system very few Cinerama theaters were built.

In fact, the Cinerama Dome in Hollywood was completed about the same time Cinerama gave up on the three strip process and converted to the single strip Ultra Panavision 70mm. Its first showing under the Cinerama banner was of “It’s a “Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World” in 1963. The theater’s Cinerama three strip projection system was never completed until about 50 years later so it could show Cinerama productions in their original format.

Wide screen actually goes back to just prior to 1900 when the designers of the Magic Lantern Shows reproduced still images noticed that if looking at the screen was like looking out a window then they should be able to “fill the entire field of vision with an image, an even greater experience sense of realism would be experienced.” Charles A. Chase designed and patented the “Electro Cyclorama” that he demonstrated over the following decade beginning in 1894.

Wide screen moving pictures got their start in 1927 with the release of Abel Gance’s “Napoleon.” The production illuminated three normal film screens and projected them side-by-side. For the finale, all three were locked together for one wide, sweeping vision. For the earlier reels, the left and right frames portrayed scenes meant to complement the action in the middle screen.

Gance’s “Napoleon” (and a later effort – Raoul Walsh’s “The Big Trail” in 1930) were judged to be “uneconomically viable” for their time but their visions would later set the stage for the Cinerama experience.

Cinerama was invented by Fred Waller, who developed a five camera version of the system named the Waller Gunnery Trainer to train air crews for World War II flight missions. At the time, the Gance “Napoleon” film was considered lost so Waller could only have known about it from a historical perspective.

The Cinerama process was very popular and brought in crowds of filmgoers to experience the magic. By 1963 it had evolved into a single strip of 65mm film shot using Panavision’s Ultra 70 format. Only two narrative films were shot using the Cinerama three camera process (“The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm“ and “How the West Was Won”) before they converted to the Panavision format and single strip 70mm format.

Another reinvention from the past was Professor Henri Chretien’s principle of anamorphotic (later to become anamorphic) photography to demonstrate refinements he had made to an 1897 design by Ernst Abbe. In 1927, Chretien appeared before the Societe Francais de Physique to describe his lens called the “Hypergonar” that “would compress an image, twice as wide as it was tall into a standard film frame when attached to normal camera” mount.

For years, Chretien’s lenses languished in storage. Then in December, 1952, Spyros P. Skouras, president of 20th Century-Fox, marked the beginning of the modern anamorphic format when he bought the Hypergonar lens and it became Fox’s entry under its trademark name “CinemaScope.” The Fox Movietone spot mistakenly called it “3-D without glasses” although the ad campaign modified this to “The Modern Miracle You See Without Glasses!”

In 1953 Fox premiered the film “The Robe” in a 2.66:1 format. Fox licensed the process to other studios including Columbia, Warner Brothers, Universal, MGM and Walt Disney Productions. According to widescreenmuseum.com, “No other technical advance in the history of motion pictures, including sound and color, gained such a high degree of acceptance among American film makers in such a short period of time.”

Theater owners were provided instructions from 20th Century-Fox on how to properly set up the system including the larger screen size.

Paramount came up with its own system. In response to Fox’s CinemaScope, they created VistaVision. In 1924, J.H.Powrie, who worked on color for still cameras came up with a frame size of 50 x 38 mm (running the film through the camera sideways with sprockets on top and bottom). In 1953, it would resurface as VistaVision on Irving Berlin’s “White Christmas.”

Unlike many of the other studios embracing CinemaScope, Paramount sought ways to improve overall picture clarity and definition on bigger screen sizes. “Paramount technicians, working with Eastman Kodak, determined that the large format negative, when printed down to standard 35mm provided a vastly improved image on screens up to 50 feet wide.”

The public responded to the wide screens bringing audiences back into theaters that had the capability of showing these wide screen miracles. The studios responded by producing films with the kind of scope to do the huge pictures justice. “How the West Was Won,” “The Robe,” and “Strategic Air Command” were just a few examples of pictures justifying what the audience came to see.

Then there were the gimmicks.

3-D keeps coming and going and never seems to catch on. It first was experimented with in 1922 with a feature length piece titled “The Power of Love.” The film used a dual-strip anaglyphic stereoscopic process (the left component is a contrasting color from the right component). Red is usually used as one of the components. “It is the only commercial film produced in the dual-camera, dual-projector system developed by Harry K. Fairhall and Robert F. Elder.”

In 1952, United Artists released the first full-length 3-D feature sound film “Bwana Devil.” A cheaply-made jungle adventure where its taglines advertised “A Lion in Your Lap and A Lover in Your Arms.”

In 1953, 3-D spanned different genres. There were Musicals (“Kiss Me Kate”), westerns (“Taza, Son of Cochise”), science fiction (“It Came From Outer Space”) and thrillers (Hitchcock’s “Dial M For Murder“). Horror was lead by Warner Brothers “House of Wax” with horror master Vincent Price in the first 3-D horror film to be in the top ten of box office hits in its year of release.

Just as suddenly as it appeared the 3-D fad was over. The last of 50’s productions appeared in March of 1955 with Universal’s “The Creature From the Black Lagoon.” Although the 3-D effect was unable to overcome the inferior quality of most of the films and theater owners were not happy about the goggles or cardboard glasses worn by the audience became expensive as it was difficult to get cinema-goers to give them back.

The audiences found the glasses unpopular and clunky and complained about how the viewing experience was blurry for them. Many people complained about headaches on nausea. But the root cause of the failure was a matter of synchronization.

If the two pictures were out of sync either through the film or the shutter, the audiences would experience anything from eyestrain to headaches and upset stomachs. Technicians looked at the various installations and found numerous cases where on film had been put out of sync because of a splice not made correctly to both prints or that the shutter on the projectors did not match. In both cases, the human eyes send the images to the brain and it tries to resolve the problem. In worst case scenarios headaches and nausea would be the result.

The final nail in 3-D’s coffin came May 19th of 1954. “Audience in Philadelphia shunned the opening day of [Hitchcock’s] “Dial M for Murder.” Warner’s had been the last hold out but with that development, all requirements for 3-D bookings were dropped. In their headline, Variety of May 26th stated, “3-D Looks Dead in the United States.”

Other gimmicks surfaced a little later. A couple revolved around the olfactory impressions of a film. Critics have complained about having to sit through a “stinker” but Smell-O-Vision and Aromarama provided a variety of smells to choose from. Again, combining film and scents is believed to have been invented in 1906 when a theater owner used a fan to send the smell of rose oil during footage of a Rose Bowl parade. Walt Disney also experimented with use aromas but abandoned them due to the high costs involved.

Smell-O-Vision was an invention funded by Mike Todd, Jr. in 1960. Only one production was made – “Scent of Mystery.” Smell-O-Vision is on Time magazine’s Fifty Worst Inventions list. Likewise, Aromarama didn’t score any points with the reviewers. They weren’t major players in the ‘Hollywood pushes back’ game since they surfaced several years later in the late 50’s. They are included since the invention was a track on the film itself that cued what scent to release.

William Castle was a pioneering horror director in 1958. He turned out low budget thrillers that had some kind of gimmick associated with them. The only one that was cued by the film was in “The Tingler.” It starred Vincent Price who was trying to cure people of parasites hiding at the base of their spines. The only way to kill the lobster like infestation was by screaming. The name of the invention was Percepto and was activated at the point the parasite gets loose in the cinema. When the audience member feels “the tingler” at work, they were advised to scream at the top of their lungs. Several stories say the system (built from surplus aircraft parts) worked and others say it was a total bust. In any case, it was another gimmick.

By the time these oddball gimmicks came on line, the battle to bring back the audiences was all but lost. Hollywood studios resorted to the old adage, “If you can’t beat’em, join’em.”

Once it became evident television was going to be around awhile, the studios, shut out of owning stations, figured out they could diversify. They licensed their films for broadcast, opened record labels and created theme parks to generate income. Going forward, television would become the Hollywood studios biggest customer filming and selling television shows!

While attracting audiences back to the theater had only lukewarm results, the film industry, by redirecting their output, did succeed in killing off live television. Live shows that were cancelled made way for a filmed program shot on studio lots. “Live from New York” quickly became “Filmed in Hollywood.”

Over time, through mergers and acquisitions with help from changes in the rules of various government agencies, the two industries have melded into one. In the United States alone, CBS Corporation owns the CBS Television network, CBS Films and has a joint venture with Warner Brothers in the CW network. Comcast owns the companies NBC and Universal Studios. The Walt Disney Company now owns the American Broadcasting Company and Walt Disney Studios. A deal to also include 20th Century Fox Studios in that mix is expected to close by June, 2019.

The winner of the battle over the who gets the biggest audience may turn out to be an industry that didn’t even exist in the 1950’s – Digital Streaming. Netflix and Amazon are becoming bigger powerhouses. The New York Times probably summed it up best in their Disney-Fox merger article, “Disney is acknowledging that the future of television and movie viewing is online.”