Glenn Ficarra and John Requa have co-written numerous feature films, including “Bad Santa” “The Bad News Bears,” and “Focus.” They also co-directed “Focus” and “Crazy Stupid Love.” Their latest directing project is “Whiskey Tango Foxtrot” with Tina Fey and, as with “Focus” they collaborated on the editing of the film with Jan Kovac in a much more hands-on way than directors – other than the Coen Brothers – tend to do. Art of the Cut already spoke with Jan Kovac about the editing of the movie, but with the uniqueness of an editing director, we wanted to continue the conversation with “Whiskey Tango Foxtrot” director Glenn Ficarra.

HULLFISH: Tell me about your editing on the project. It’s a bit unusual for a director to actually sit at the controls in the edit suite. Why do you feel the need or desire to be part of the process beyond the typical editor/director collaboration?

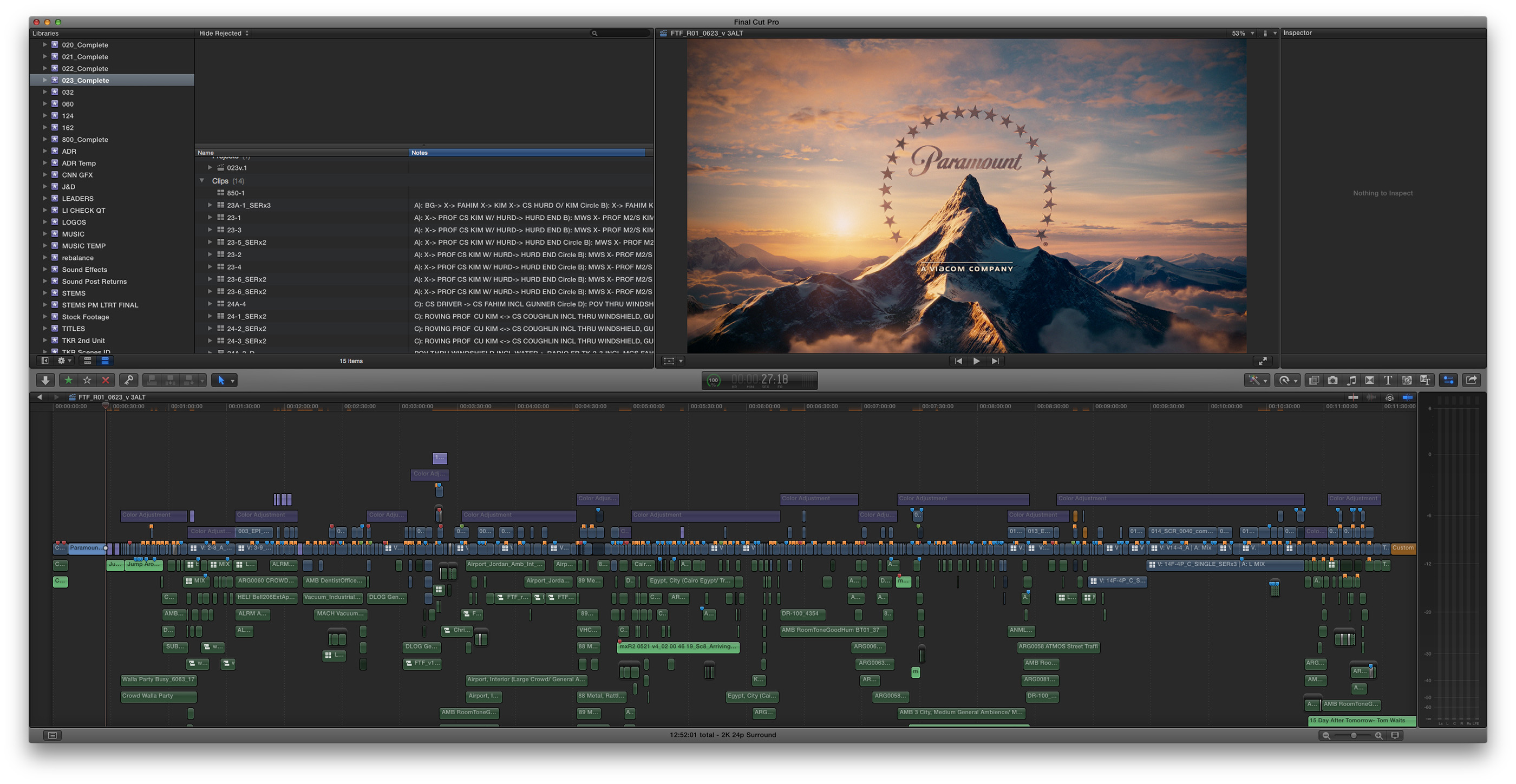

FICARRA: I came up as an editor and an assistant and doing opticals, so I’m very comfortable editing. It’s just easier to DO your notes as opposed to GIVE your notes. (laughs). And that way, people can be doing other things. But mostly it leaves more room for experimentation and fun without sending the editor on a wild-goose chase of things that you’re thinking. It’s kind of worked for us. We have a unique fit. I mean Jan is by far doing the bulk of the work and John and I are on the side working on a separate system. Sometimes John will sit with Jan and sometimes John will sit with me and sometimes I’ll sit with Jan while John is on a system picking takes. It’s kind of a nice triumvirate.

HULLFISH: I’ve cut three films and all three of them have been with directors who also edit. Why did you feel like you shouldn’t take an editing credit?

We’re just trying to move the post-process in a little more progressive direction and it’s good for it to be a hands-on experience to really get into the workflow to see how we can make it better. (ABOVE – Editor Jan Kovac and Assistant Editor Kevin Bailey going over notes)

HULLFISH: Sure. And with your background in editing going back as far as it did, you can’t have always edited in FCP-X.

HULLFISH: So you spent a lot of time as a writer and I think editing is very similar to writing, don’t you think?

FICARRA: A lot of people say, “editing is the final re-write.” I believe that. Editing is very akin to writing and John and I really treat it as such. We’re really flexible and because we’re so collaborative as a writing team, we’re constantly re-inventing the movie. That’s the way we work as writers. I find it very similar. Little moves can mean a lot. Even the intention of what you did is not necessarily what you’re committing to.

HULLFISH: The intention of what you did in the writing? I’m not following.

FICARRA: The intention of what you did on the set doesn’t necessarily have to be what you put up on the screen.

HULLFISH: That’s true.

FICARRA: You might have shot a scene to be dramatic and decide that you want to make it comic, or withhold information or anything like that. It’s just so similar to writing it kind of comes naturally.

HULLFISH: Jan was talking to me about you guys “bracketing performances” when you direct. Can you talk to me a little about that?

FICARRA: Because all of the movies we’ve done have been these mixed-tone movies we they’re kind of made in the editing room as far as shading the performances and the arc – where a movie might start funny and get more serious as it goes along. That requires us to have more control over the performances and the actors really like it because they’ll do a comic version of a scene and serious version of the scene without changing the script much. It’s all them doing the work and it gives you lots of choices later on – sometimes too many.

HULLFISH: What are the practicalities or realities of “bracketing performances” on set. How are you directing people? Or do you start with the comic version first and then go serious or vice versa? And how many shades are you trying in between?

FICARRA: It’s just a couple. Usually the scene is what the scene is. When we’re in certain parts of the movie when we’re unclear how serious they need to be or how comic they need to be, those are the places where we we’ll get the choices. It’s not every scene. You’re usually talking about hitting the intention of the scene as read and then “Oh, if we want a laugh here we could always do this…” Then we throw in a joke or an improv. It’s not much different than working with actors and doing a scripted version and then we’ll improv. We’ll do a couple of improvs and see what happens and you follow along with coverage. It’s not necessarily one way or another, but if a scene was written as more dramatic, that’s what we do first and then add stuff to it.

HULLFISH: One of my editing interests as you go through a movie is these big jumps in time that you guys don’t bother to prep the audience for, you just figure that after the first couple of skips, the audience gets used to the fact that that’s the way the story is going to get told. Talk to me about how little story you need to let the audience in on or how little information is really necessary to parcel out to the audience to have them follow the story.

HULLFISH: Talk to me about that process of putting something in front of a test audience. I’ve talked to a couple of different editors about the idea that the chemistry of the movie or the chemistry of how you view the movie changes pretty radically when you watch it with an audience.

FICARRA: Oh God yes. Everything you ever thought was going to be funny or anything at all goes out the window. And you can feel it. You don’t even need to hear it. It’s so valuable in a comedy. It’s a humbling experience. It definitely informs you of what the audience is digging in on and what they’re getting a kick from and there are so many permutations and so many reasons why they might get a joke or not get a joke. I find it endlessly fascinating, even though it can be terrifying too, especially comedy. I found in this movie that people were really… we moved through the set-up of this movie really quickly. And that was the audience, “Well I’ve seen this movie before.” Of somebody miserable in their job and all that and it used to be twice as long and it worked and it was fine, but it was like, “Let’s just get to Afghanistan.”

HULLFISH: There are really only two scenes I think in New York.

FICARRA: Three.

HULLFISH: The scene where they ask the childless unmarried people to go, the scene where she’s on the stationary bike…

FICARRA: And the scene in her apartment where she tells her boyfriend she’s going to go.

HULLFISH: … She’s on the phone and he’s out of town.

FICARRA: There was a big argument to remove it all and just start the movie on the plane and just back-fill the story. A lot of this came from the fact that our budget was very low for this movie because it’s not the kind of movie that’s going to make a lot of money. It’s like a prestige thing. The studio really loved the script but we had to make it for a price, so we had to cut a lot of the stuff in the script and most of that stuff came out of New York. There was a whole argument – not a contentious argument but a discourse – about treating it like a Grant Greene novel and just doing the whole thing in Afghanistan and anything that happened before is just backstory that comes up in other scenes. Knowing that we shot scenes to support it but we also had various places where we dropped in backstory, but that’s not in the movie anymore. But we shot it so we could take out all reference to New York. We had kind of a back-up plan of other ways to do it.

HULLFISH: Was the structure of the movie as it stands now the structure of the script with the beginning already in Afghanistan for a scene then jumping back to New York and restarting from the beginning?

FICARRA: Yeah. That was in the script, which I think was a smart decision because it gives you something intriguing upfront and then you’re waiting till we get there. “How did she get to that point?” We get to see that. Ostensibly, she’s a seasoned reporter and then we flashback to when she’s not. It gives you a shape of the movie before you watch the movie.

HULLFISH: Talk to me about structure and the ways that the final version is similar to the scripted version. Can you think of big changes and why those decisions were made?

FICARRA: I think it was a lot of re-ordering. It was a delicate balance because by nature it was a very plot-less script. It’s really a slice-of-life character study and it would macerate in all of these situations – just kind of like being in a war zone is. It’s not really a direct narrative. The scripted version as edited in the assembly was three hours long and we immediately said, “Let’s strip it down to the bare essentials and make sure this buy-in is there.” So we stripped it way down and that didn’t play right. It didn’t feel like it had enough aimlessness in it, so we kind of folded some of that back in, some of the flavor. So from a plot perspective – of which there is very little -nothing changed. From a textural point of view a lot is gone. Great scenes fell out that didn’t have room in the movie. When we started to get too far away from the basic story of her and more about Afghanistan as a whole or reporters as a whole, it started to lose its drive, so we found by sticking with her character, we really found the path.

HULLFISH: That’s one of the interesting things of you guys working as editors on your film that I also find happening with the directors I’ve cut with is: I think it’s a struggle sometimes for a director sometimes to cut those great scenes.

FICARRA: Oh, we’re not precious at all. I think that’s from all of our days of writing and seeing our scripts be made into movies whether we directed them or not. It’s VERY rare cases where the script is the script. What actors can do with a look as opposed to saying the words… you have to be brutal. They call us “The Butchers of Burbank.” (laughs) We’re so not precious about our own scenes or everything we love. So that thing where you have to be willing to kill your babies is first and foremost.

HULLFISH: In the script you need the dialogue to tell the story, then you get into the edit suite and somebody will give you a look that makes the four lines of dialogue that they say after it superfluous.

FICARRA: Yeah. We had three scenes of Kim and Ian falling in love in the movie, getting closer and closer, and now it’s one scene. It all falls out pretty naturally I always find. And that’s what those test screenings are so great for. You can tell in the second conversation that Kim and Ian have and the audience is going, “Aw, that’s cute” and you realize, that you don’t have to take it any farther or spend more time on it so let’s condense the scenes.

HULLFISH: How do you and John co-direct? People think of a director being the sole vision/auteur thing. How can two guys direct a movie?

FICARRA: Did you ask the Coen brothers?

HULLFISH: (laughs)

FICARRA: We know Joel and Ethan and we were able to hang around a few days on “The Man Who Wasn’t There” and observe and they work very similarly to the way we do which is – first of all we’ve been writing together for 30 years. Everything we write we write in the same room together. So we really are of one mind. And when we’re directing something we haven’t written, we have long, extensive conversations ahead of time. We usually board the whole movie out, so we’re forced to have those conversations of how to cover things, what’s important, what’s not important. So, there’s tremendous amount of prep to make sure that we’re not disagreeing on set.

HULLFISH: And on set are you both talking to the actors or one of you guys is sitting back at the monitor and the other is working with the actor because you know you’re of one mind? Or how does that work?

FICARRA: It’s very organic and it’s essentially 50/50. We try not to talk to them at the same time. We might take turns. We’re always both present for the notes, but we try not to confuse them by giving them too different opinions or too much adjustment at once. We really prep visually so the D.P. knows what we want to do and we’ll throw some ideas out there, but it’s a very natural process and it’s only rare occasions where we disagree. Invariably one of us feels more passionately than the other and we trust each other.

FICARRA: We often will – at lunch time maybe – watch some dailies or go through things and say, “How about this take or that take?” But Jan was cutting from the get-go obviously and he had a trailer on set so we could go in there at lunch and at various times and he could bring us stuff on a laptop. I think in the perfect world what we always liked was, we’d get dailies and either over a meal or something we would all stay in the same complex on location, so we would just hang out and watch dailies and talk about possibilities. Usually our first conversation was just about the shape of the scene: what was intended. We also brought Jan in on the boarding sessions and those conversations, so he was pretty prepped. Even though that’s what we intended that’s not always what the scene needs so once we start watching the assembly as a whole we’d watch to a point and then go, “Let’s do some work here. You work on this and I’ll work on that montage.” Sometimes if we’re just looking at ideas, as opposed to Jan do five versions of something, we’d have him do this version and that version and I’d do these other three versions. It just takes less time and it’s more iterative. But sometimes we’d break up reels. Jan would work on a reel and John and I would give notes on that reel and then John and I are watching the second reel and changing stuff and take that back to Jan and he’d watch that and he’d have ideas and he’d do those. So there’s probably ten different ways that we collaborated. Sometimes it’s just John and me sitting on a couch with Jan giving notes. We just do it till we’re satisfied. Any way that works.

HULLFISH: A very organic method basically.

FICARRA: Yeah. There are no hard and fast rules about how we do things. There’s no battle for the best idea. There’s none of that. A good idea is a good idea. It might come from something really crazy. We’ve got the time to try things that might not be worth pursuing in the room because I’ll slip out and try it on my own: “This is interesting if we reveal this before we reveal that.” Let’s slap it in the reel and see what happens. It’s very organic.

HULLFISH: Can we talk about four specific scenes? Talk to me about the “unmarried childless” scene in New York.

FICARRA: It was actually a much longer scene. It was written long and it was always intended to be this oppressive lighting, lifeless thing. That was the visual intent of the scene. There were a lot of jokes in the New York section of the movie. We found that it was playing too broad and immediately we decided to cut it down to what we need and maybe one on-character, solid joke is all we need here. And so the crying joke was always in the script and we decided that was the funniest thing and to make that pay off we needed the “unmarried childless” line before it for the set up so we built it from there and backed into it to see how little we could get away with because we were really interested in moving through the New York stuff as quickly as possible because we felt like people have seen that movie before.

HULLFISH: And the movie just needs to get to Afghanistan to get started.

FICARRA: Yeah. And we didn’t want it to play like a movie they’ve seen before where we would spend 20 minutes in New York. I mean, five minutes is plenty.

HULLFISH: The classic scriptwriter thing of spending the first act being somebody in their “home” world” before they make the journey to a new world in the second act…

FICARRA: Right. Right. I think the script as written played to these kind of genre-bending moments. And it bothers a lot of people. I have to say, but that’s not going to stop us really. (laughs) John and I and Jan firmly believe that these formulaic patterns – you might call them classic, you might call them the pillars of storytelling – I don’t believe that. I really think there’s room for mashing up styles. I think there’s room for a lot of things. And we really applied that lesson to the set-up of this film.

HULLFISH: So really the first act is more about her going from rookie/novice to veteran.

FICARRA: Absolutely right. I think it’s 20 minutes in she’s into the life pretty hard in Afghanistan and that’s when the story really kicks in. It’s a very odd movie because it’s very plot-less in the way that “M*A*S*H” was. I think that Robert Altman movies were famous for this where you think the movie is about one thing, but they tend to go off on these tangents and it’s more about the characters and their lives than it is about plot. When the studio said they wanted to make it John and I were like, “Really? You do? ‘Cause you guys don’t make movies like this anymore.” We were really into doing it because you don’t get a chance to make movies like that these days.

HULLFISH: Tell me about the scene “Can I have sex with your security guy?”

FICARRA: That scene is basically “as written.” There’s a power outage in the scene that really happened on set. There were power outages in Kabul every three hours, so it was fine. You see the lights flicker on and off and we just kept it.

HULLFISH: I was trying to figure out if it was in order because Kim is trying to get to the shower and she’s just come from meeting Tanya in this room full of men and it seemed some stuff got changed to me.

FICARRA: It did get reordered. In the original script, Kim came in and met the people in the downstairs, met Tanya and then she went back and called her boyfriend and everything and we – on the set we came up with this very simple little scene of her laying there listening to the sounds of Kabul at night. So by necessity we had to cleave the scene off where she meets Tanya. I think that’s how it ended up. We reordered it so many times. (laughs)

HULLFISH: I know that drill.

FICARRA: It’s funny. I’ve seen the movie about a million times and it doesn’t stick. But you’re definitely right. It’s out of continuity of the script, but it was in that order for a long time. There was a little more backstory in that scene originally that fell out.

HULLFISH: It seemed like a very Tina Fey kind of scene.

FICARRA: Yeah it did. But Margo Robbie is fantastic in that performance and just nailed it. It’s just a great introduction to a character. Originally it was one of those scenes that carried water for a few things. It had some backstory. It had this and that. There were a few things going on in it and it was one of those cases where the scene should be about one thing or about nothing. So it had to be about the one thing: which was introducing Margo.

HULLFISH: Fahim – I loved his character – there’s a scene where Fahim is basically telling her he doesn’t want to work with her any more. And after he leaves, there’s a series of three jump cut close-ups of Tina’s face, cut to cut to cut.

FICARRA: That is the midpoint of the movie. That’s where all of the stakes change. Where things become a lot more real. She’s not only gotten into the life and gotten what she wanted, but she’s starting to flip to the other side and in the script it’s a kind of a slow roll from one end to the other and once that landed in the middle of the movie, we kind of wanted to highlight the moment. We really just like it. It’s like a passage of time of her coming to grips with that decision. It’s really about her making a choice. It’s the beginning of the descent of her character really into the addiction to the lifestyle.

HULLFISH: I liked it. You have editing rules, but you have to know when to break them and why to break them. I definitely felt like you broke some editing rules in there in order to allow the audience to get into her head.

FICARRA: Yeah. It was to get into her head. To me, it always felt like it was her processing that and the two sides of her personality, wrestling. The old Kim and the new Kim and it illustrates the new Kim taking over.

HULLFISH: Have you seen “Sicario?”

FICARRA: Yes. It’s a lot of the same cast, actually.

HULLFISH: I interviewed Joe Walker about “Sicario” and there’s a scene in “Sicario” that’s very similar to a scene in “Whiskey Tango Foxtrot” but the difference that’s shocking was the musical choice. “Sicario” has this scene where the special ops guys are going into the tunnels at night. You’re kind of embedded with these special ops guys. And then you guys have a scene where a special ops team is going in after somebody, but the musical choices are completely different. “Sicario” has this menacing, grinding, filthy drone. But you guys played the music under the same basic images completely differently.

FICARRA: This was something that went throughout the movie. We are not making an attempt at an action movie. The visuals were a lot of what you’d expect out of a scene like that but this movie doesn’t really support those kinds of scenes. Even the first firefight scene with Kim’s trial by fire, it’s all played from the inside of the Humvee and it’s her point of view for a reason. We weren’t interested in doing “Saving Private Ryan” there because it’s not that kind of movie. Plus it’s all subjective to her. We thought it was interesting to take that music and reflect her viewpoint. To go into some interesting score didn’t feel right for the movie. It made it feel kind of hackneyed. The original intent of the movie – in the original script, that scene doesn’t even exist. They kind of go off to get him and it’s very brief. We played with music and found some songs that were very haunting, but all the ones that seemed to work were ones that spoke to “this is a gesture of love.” One of the songs we tried was “Love Letters” which is also used in “Killing Them Softly” where Ray Liotta gets killed and that song worked really well, but they had used it in that movie, so we decided to find something else with that similar vibe.

HULLFISH: What was the track?

FICARRA: Harry Nilsson’s “Without You” is what we ended up using. It’s this 70s sad ballad and it means different things to different people interestingly. To younger people they just think it’s really cool. Old people like me think it’s an ironic choice.

HULLFISH: I thought it was just showing her viewpoint. It’s like a little love letter.

FICARRA: That’s exactly what it is. That choice is because this is a romantic gesture and it’s playing into the rom-com element of this movie which is very oddly placed in this warzone and it was another way to point out this weird juxtaposition.

HULLFISH: But you did try to temp it with some other stuff… that wasn’t the choice from the beginning.

FICARRA: We had a very minimal tonal score there which worked but it felt a little cliche.

HULLFISH: And did the movie end the way it did in the script?

FICARRA: Mostly. There were some re-orders and some things that fell out, but yeah. I think the one thing that was really expanded in editing was her goodbye to Fahim. That was something that – I don’t want to say that it was created in the editing room – but it was greatly exaggerated. Because Fahim is kind of the moral center of the movie and he represents Afghanistan, which she has this complex relationship with – she hates it but she loves it. And the real Kim still misses that place. I’ve had those conversations with her. We thought that goodbye really needed to mean something.

HULLFISH: I personally liked the relationship between Kim and Fahim better than the relationship between Kim and Ian.

FICARRA: Yeah. It’s definitely the central relationship and Ian is kind of a dead-ender. He’s going to live this life forever. He’s a real addict and it’s like having a co-dependent relationship. That’s really what their relationship was. That addiction was standing in the way.

HULLFISH: Any final thoughts on your feelings on FCP-X.

FICARRA: It just lets me spend more time editing and less time preparing to edit. It’s just really just powerful and gets as deep as you need to get. We’ve gotten pretty deep with it, but you can approach it at a very simple level or go in and really exploit the depths of the data-base and the organizational features. It was really great. I haven’t used Premiere much, but Premiere looks really fun too.

FICARRA: Actually I think it’s even more powerful. And we barely scratched the surface of it because the way you can do things can get really interesting. And I don’t think there’s any one workflow just yet. We experimented on stuff with “Focus” and changed it for this movie and I think we’ll even go even deeper next time.

HULLFISH: What did you change between “Focus” and “WTF?”

HULLFISH: OK. That’s what I’ll do. Interview with him next, then.

FICARRA: Kevin (pictured left) is amazing and he’s got things really well thought out as far as this goes and he was really a vital part of the process. He knows it intimately. He used to work at Apple and he’s an excellent assistant editor in his own right. He used to work for Walter Murch and he knows his shit, so he’s great for sound and all of that which is where he really helped us. Just keeping the train running smoothly.

HULLFISH: Thanks for all your time. Good luck on the success of the movie. I thoroughly enjoyed it.

FICARRA: Good to hear. Thank you very much for seeing it.

To read editor Jan Kovac’s interview (pictured right) on “Whiskey Tango Foxtrot” or other interviews in the Art of the Cut series, use THIS LINK. Also stay tuned for other additional interviews in the series and follow me on Twitter at @stevehullfish