Introduction

There’s nothing more certain than change. My first hard drive was 20MB in size, but since the days of floppy disks, we’ve gone through Zip and Jaz drives, various speeds of large and small spinning drives, many proprietary media cards, USB sticks, and have now settled on SSDs with USB-C connections as the video editor’s mobile storage device of choice. Some of us shoot directly to them, some of us just use them to edit, but they’re everywhere, and for good reason.

With no moving parts, SSDs far more resilient than spinning disks, which are still widely used for archiving (if tape is a step too far) and in RAIDs. They’re far faster too. But still… sometimes they’re just not as fast as they should be. What’s all that about?

Different kinds of internals

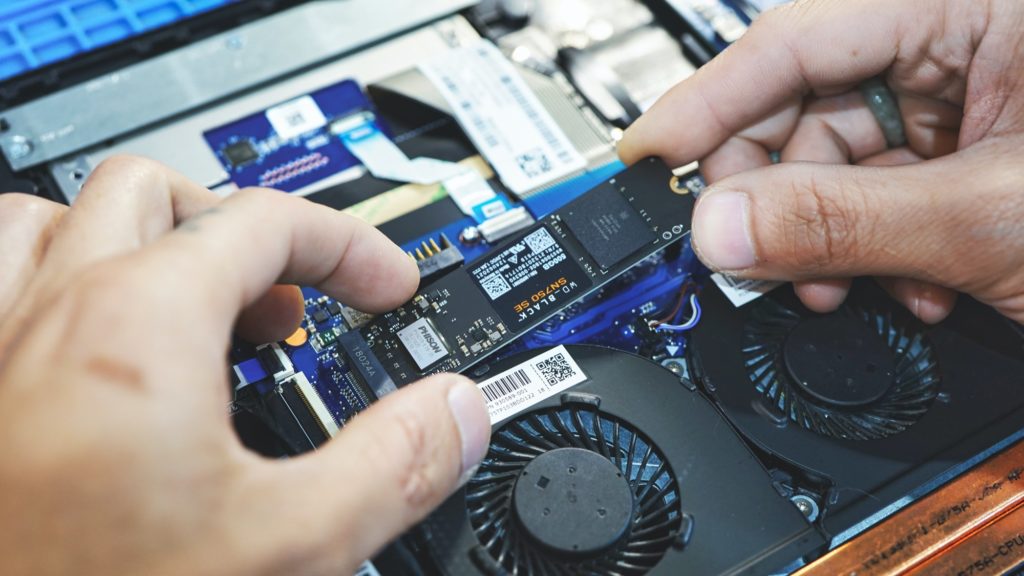

While most people buy pre-built external SSDs, you can also buy SSDs designed to connect inside a computer, or to be placed in a generic empty enclosure. Different standards over the years have operated at different maximum speeds, so an SSD with SATA internals is no longer top-of-the-line.

Today, most SSDs use an NVMe connection internally, and are in the M.2 form factor. Be careful if you do decide to build your own drive by assembling parts — you can buy SATA drives in the M.2 form factor, but some enclosures only work with one of the two standards. NVMe is faster, so go for that if you can. Note that there are different PCIe standards used in NVMe drives, and the newer ones allow for higher speeds, but watch for compatibility issues with older enclosures.

Same plug, different speeds

As SSDs have further developed, the connections available on our computers have been changing too. USB and Thunderbolt have both settled on the USB-C port, as have Macs and most PCs. The only problem is that while USB-C ports and cables look the same as each other, they might not work the same, and the USB consortium hasn’t helped with a confusing naming scheme that’s changed many times over the years — even renaming existing standards along the way. Still, it’s not too hard to read between the lines and figure things out.

- If a drive is marked as USB 3.1, USB 3.2 Gen 1, or 5Gbps, it’s a relatively slow drive that should deliver about 500MB/s copy speed. That’s still pretty fast compared to a spinning disk (100-150MB/s) but it’s not amazing. SATA drives top out here.

- If a drive is marked as USB 3.2 Gen 2, or 10Gbps, it should be able to deliver about 1000MB/s copy speed. Annoyingly, not all 10Gbps drives can connect to all Macs at this speed, but if you connect them via a Thunderbolt dock, they should. Today, this is the higher end of most consumer SSDs, but you can still do better.

- If a drive is marked as USB 3.2 Gen2x2, or 20Gbps, unfortunately will only deliver that speed with a very few PCs and no Macs, because that flavour of USB never really took off. On other machines it’ll perform the same as a regular USB 3.2 Gen2 drive, at 10Gbps.

- Finally, if a drive is marked as USB4, Thunderbolt 3, or 40Gbps, you could see very fast speeds indeed, and it’ll probably be down to the SSD itself to keep up with the connection. You will need to use a Thunderbolt port for this level of performance, but most Macs include at least two of these. Watch out, though — many straight USB 3.1 Gen 1 devices will list “Thunderbolt compatible” in their specs, and that does not means they are Thunderbolt drives. Yes, they work in Thunderbolt ports, but they’re just plain USB.

Right now, 10Gbps drives are widespread and the best value. Beware of cheaper SATA drives, as some newer budget options use awful, inconvenient microUSB ports. You’ll also still find that USB4/Thunderbolt SSDs are much more expensive than USB3 SSDs, because the USB4/Thunderbolt controller chips they use are still pricey. Eventually this will change, but there’s a big premium on speed right now, and it might not be worthwhile. Why?

A copy is as slow as the slowest link

It’s all very well to have a drive that can do 3000MB/s and higher, like the internal drives on higher-end Macs, but unless you have a second drive that can match it, and you want to copy to or from that drive, all that potential is wasted. You need to move data between two amazing drives to see amazing performance, and you have to do it often enough, in a time-critical environment, to make this worthwhile.

Also, if you were hoping to use a fast SSD to speed up media copies in the field, think again. The vast majority of regular media cards can deliver data at a rate under 200MB/s, and you can’t improve that without spending a lot of money. If you avoid media cards by using an external recording solution instead, remember that they tend to record larger files, and that most SSDs used by external recording devices are SATA-based. A fancy 2000MB/s Thunderbolt SSD will still be limited by a 500MB/s SATA drive, and you can’t utilize all that potential unless you’re copying from two or more slower devices to one faster one, all at once.

It gets worse.

It’s all about the cache

Some modern SSDs can, in some circumstance, be slower than older SATA drives, and this is down to the design of modern drives. Older SATA drives might have been relatively slow, but they were consistent, and better SATA drives could write at 500MB/s consistently, until they were full. This is crucial for video recording devices like an Atomos, where a minimum write speed must be maintained or you can lose a recording. That’s not how most drives are built today, though, because we demanded higher capacities.

In the NAND chips that make up an SSD, older drives used SLC (Single-Level Cell) technology, storing one bit per cell. Since then, we’ve moved through MLC (2 bits/cell), TLC (3 bits/cell) and we’re at QLC (4 bits/cell), increasing data density and lowering cost. Writing data to these more complex cells takes longer, and a common way to improve speeds is to write to a small amount of faster SLC cache first, then rewrite it to the denser, slower storage areas. (Some drives can cheat, writing to dense QLC cells as if they are SLC cells, but this only works well when the drive is empty.)

Most SSD users don’t mind this at all. They get a larger drive, with potentially faster specifications, and as most users write lots of small files infrequently, it works well. But it’s awful for video editors who want to dump several hundred GB of data all at once. Once an SSD’s cache is exhausted — and that can happen after 100MB or less — the copy speed can plummet. This cache issue, not heat, and not connection type, is one of the main reasons why video editors need to be careful what drives they buy.

Misleading benchmarks

Do not trust any review that just loads up Blackmagic Disk Speed Test and presses go. Those are small repeated reads and writes, and are not going to tell you how this drive is going to perform in a large copy operation. The only site I’ve found which reliably runs these tests is Tom’s Hardware. Here’s a review of the older but popular Samsung T7, and it’s worth a read through. On Page 2, you can see the graph you need to care about, under the heading “Sustained Write Performance, Cache Recovery, and Temperature”.

Only the first 84GB of data could be written at the full 867Mbps speed, after which the speed crashed to 337Mbps. If you’ve used one of these drives in the field for a large copy, and wondered why, it’s the small cache. The drive’s successor, the Samsung T7 Shield, doesn’t lose anywhere near this amount of speed on longer copies, so it’s a much better choice for video editors. The SanDisk Extreme v2 is a good option too, and of course there are faster options for those who can actually make use of them. The SanDisk Extreme Pro is one drive that tests well, but if you don’t have a USB 3.2 Gen 2×2 connection, you won’t see much improvement.

Conclusion

If you’re a video editor, you are not a regular SSD user, so don’t buy a drive unless you know it can handle lengthy sustained writes. Don’t buy a drive with insane performance unless you have a machine that can use it, and another drive with similar specs. And do back everything up! Data loss can still happen, even without moving parts. It’s not as hard or as pricey as you might think to buy a good drive, but don’t just go for the most popular drive at your local big box store — read the right reviews instead.

Lastly, if you see a no-name SSD at a price that’s too good to be true, it’s likely a scam. Stay with brand names with warranties, whether you build-your-own or buy an external drive. Happy copying!