writ·ing | ˈrī-tiŋ

Definition of writing: the act or process of one who writes such as:

a: the act or art of forming visible letters or characters specifically;

b: the act or practice of literary or musical composition

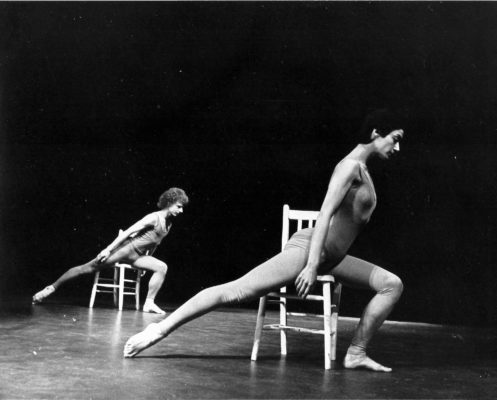

Sorry Mr. or Ms. Merriam Webster, but I don’t think you go far enough. I’m glad you include “musical composition” as one of your definitions of writing. I would venture there are many languages of expression in all art forms which “write” or tell stories through actions other than words on a page.

As a choreographer, I used body movements as my first “language” of creation. Artists use paint strokes, placement of objects, and a myriad of other storytelling techniques to get their message across.

As a choreographer, I used body movements as my first “language” of creation. Artists use paint strokes, placement of objects, and a myriad of other storytelling techniques to get their message across.

You can extend that to architecture, sculpture, mask-making, food creation, photography, and any other means of human expression to heighten, inspire, or otherwise lift the viewer or participant.

You can extend that to architecture, sculpture, mask-making, food creation, photography, and any other means of human expression to heighten, inspire, or otherwise lift the viewer or participant.

Which brings me to the difference in “writing” in the Scripted and Unscripted worlds.

How do you write in an unscripted world?

The word Unscripted is, in fact, misleading. There is a lot of “writing” in the factual or unscripted world. Some of it happens before we shoot, some of it during, and a lot after. Contrary to the scripted world, where a lot of writing happens in the script before a project is even greenlit, there are a series of documents in the unscripted world to alert the production company, broadcaster, and crew, about the intention of a show, episode, segment or participant, and how the team is going to go about capturing the moments.

Gone are the days of documentary filmmaking where one could simply follow a person, family, tribe, or community, around for a year, documenting what happens to them, pointing the camera at whatever happens, and then deciding later, what of the story is going to be told and what is not. The brilliant documentarian Allan King made wonderful films such as DYING AT GRACE and A MARRIED COUPLE that took years to make, and many of today’s brilliant documentary filmmakers like Ric Esther Bienstock and Ann Shin are able to take the time and somehow find funds to make fantastic work in this genre. But in the “time is money and we have to deliver!” world of doc/reality TV series, this kind of time and approach simply isn’t possible. So what’s a dedicated filmmaker to do?

It is in fact writing and forming guidelines for the intentions of the show or series that allows the filmmaker to condense the process and hopefully not drown out spontaneity and creativity, which are the essence of filming real people in their real lives. This is the joy of it. Again, in Unscripted, it’s all about “intention” – what are we trying to say? And what is best to film in order to say it?

Here’s where writing in Unscripted occurs:

1. Casting – If the most important person on set is in front of the camera, then the casting team needs to know what kind of participant and situation the show episode requires. Is it someone who is desperate to sell their house because they got a job in another city and for some reason, their house isn’t selling?. Is a marriage on the rocks because of the debt one of the spouses has run up and they are constantly battling over this? Is an ice dancing team at the bottom of their rankings because one of the skaters has sustained a horrific injury? You can see the pattern here. In these kinds of shows, how can our show team or expert help these participants save themselves by turning up with their skills? Once a producer communicates that to the casting team through writing and live discussions, the team can go off and look for the right person and situation. It’s all about intention here and everywhere. The casting team may not find the exact person the “script” is looking for but may turn up another story which is even better, and the episode can make a sharp turn in any direction.

1. Casting – If the most important person on set is in front of the camera, then the casting team needs to know what kind of participant and situation the show episode requires. Is it someone who is desperate to sell their house because they got a job in another city and for some reason, their house isn’t selling?. Is a marriage on the rocks because of the debt one of the spouses has run up and they are constantly battling over this? Is an ice dancing team at the bottom of their rankings because one of the skaters has sustained a horrific injury? You can see the pattern here. In these kinds of shows, how can our show team or expert help these participants save themselves by turning up with their skills? Once a producer communicates that to the casting team through writing and live discussions, the team can go off and look for the right person and situation. It’s all about intention here and everywhere. The casting team may not find the exact person the “script” is looking for but may turn up another story which is even better, and the episode can make a sharp turn in any direction.

2. Outline – Once casting of a participant has been approved, the producing team creates an outline of the issues that the participant is facing and how the show expert or team could help that person face their issues and hopefully succeed. Or not, depending on what actually happens. Again, it’s all about what the intentions are.

3. Beat Sheets are created to give an indication of what we think might happen and when we project it could happen if it does. In the case of an ongoing show like Storage Wars or Ice Road Truckers, we can never predict what could be in that locker or which horrific possibilities await our intrepid truckers when the ice melts each year, drowning their hopes/dreams and potentially trucks and lives. In these shows which are climate and/or disaster-dependent and unreliable for storylines, the beats might monitor a participant’s personal relationships we’ve been following with their friends, family, and colleagues. Once again, it’s only a projection of what might happen if an impending storm happens or if a couple gets into a horrific fight. What’s written on the beat sheet one day, can easily end up in the trash can the next. Sometimes it can vary from hour to hour.

4. Production – As the episode is being filmed and the projected activities do or don’t happen, and a slew of unexpected “gems” turn up, (a truck goes through the ice, a ship blows up, someone goes into labor, etc.), the crew is forced to pivot, change course, adjust, and sometimes begin following a whole new storyline.

This new direction has to be conveyed from the field back to the production office so plans can be rearranged and adjusted through the ranks of producers and broadcast execs in written form. An experienced director/producer in the field will sometimes have to make decisions quickly so the crew needs to know whether to keep filming or not. Do we roll camera if a truck is going through the ice? You bet! As long as safety procedures are implemented and no one is at any kind of risk, the decision must be made whether to film or not. Is a person going into labor an important part of our story? If so, how do we get clearance or access to a hospital? Maybe we don’t. Logistical problems have to be solved as the new beat sheet barrels along at breakneck speed.

5. Post-production – Writing often saves the day once again. If you don’t think editing is a form of writing, you might have to face a dedicated passionate editor in a darkened editing suite who will definitely point you in the right direction. Just as every choice a camera shooter makes when they are framing a shot, every cut/paste/dissolve/swipe choice made by a skilled editor is another “word” along the way of writing a scene/show/episode whether in unscripted or scripted.

Writing in the Scripted World

You might think the writing process in the Scripted world would be much simpler, right? Wrong. We are taught there are three phases of writing in a narrative film:

1. The Script

2. The Shoot

3. Editing

Let’s break that down:

1. The Script: Before a project ever gets to the shooting phase, the script will go through a myriad of changes and rewrites. Depending on the show if it’s a series and who’s the “boss”, those changes and rewrites can keep occurring right up to shoot day and sometimes beyond. If it’s an independent movie or short, rewrites are also continuous, depending on unexpected events, situations, weather changes, locations, etc.

2. The Shoot: It’s the director executing the next phase of writing at this point. Again, depending on the show and it’s shooting style, the script can be loosely constructed with room for improvisation or changes depending on the cast, line delivery, etc. Sometimes a lead actor (who knows his or her character and the show better than a guest director) will say “I would never say that” so approvals need to happen spontaneously and the writer and showrunner need to weigh in to make sure that whatever is replacing that line of dialogue or action makes sense in the overall arc of the episode or series. A visiting director might also request script changes before going to camera if a scene or line just doesn’t make sense to them or can’t be shot properly in a given location.

If it’s an independent narrative feature or short, the director might make a lot of changes or try different takes in different styles to see which one works. There’s not a lot of time for this usually but that depends on the director’s particular style. Some want the actors to speak their lines exactly as written and some prefer a lot of improv to get just the right tone.

3. Editing: As in unscripted, a lot of writing actually happens in the editing suite. Which shot best works to convey the emotion or action of a scene? Closeup? Two-shot? Wide? There are choices once again made in every moment of the show or movie that the average viewer will never be aware of. The final post-production elements will make or break a show as every good filmmaker knows. We always need to give credit to those unsung heroes laboring away hour after hour in the shadows to make the film be as marvelous as possible.

So as you can see, the art of writing is very much alive in every phase of unscripted or scripted filmmaking right up to the final stages of music, color correction, image stabilization, titling, and the addition of special effects. Good storytelling is exactly that, and the rules of engagement and holding the viewer’s attention applies to both worlds. When I’m writing in Unscripted, I’m aware that I’m like Picasso doodling, and I am required to create a great story with speed and agility. In Scripted, I’m granted the joy of painting in oils and have just a little more time to concentrate on character and the depth of story. But a good writer who understands and can execute good story structure in one field can translate those skills into the other. Every single element in every single frame is part of a story that’s being told, hopefully by brilliant storytelling artists contributing to the greater picture with every ounce of their commitment and dedication.

Unscripted vs. Scripted:

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now